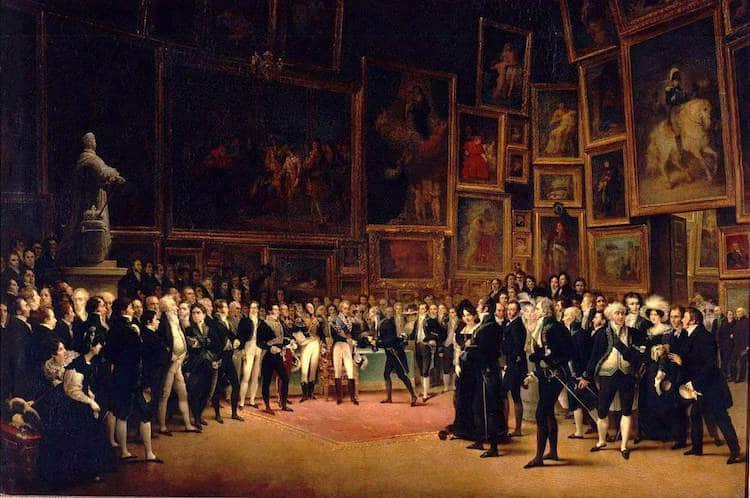

François Joseph Heim, “Charles V Distributing Awards to the Artists at the Close of the Salon of 1827,” 1824 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In 1874, several artists based in Paris banded together to hold an independent art show. Later known as the Impressionists, these figures took it upon themselves to present their own paintings, prints, and sculptures, bypassing an external selection process. Today, this may seem like standard practice. In 19th-century France, however, it was considered a radical move, as it subverted the Salon.

At this time, the Salon served as Paris' premier art exhibition. Organized by the prestigious Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (“Royal Academy of Painting and of Sculpture”) and led by a jury with the power to pick and choose what work was worth showing, this annual event could make or break artists' careers. Most importantly, however, it had a profound effect on European art as a whole, as it enabled an elite organization to dictate the definition of art.

Today, the Impressionists are known for their radical rejection of the Salon. While these figures were the first to hold alternative exhibitions, they weren't the last. Before taking a look at the official show and its various offshoots, however, it's important to understand the history of the salon in France—a role that begins with academies.

Academies in France

Jean-Baptiste Martin, “An ordinary assembly of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture at the Louvre,” ca. 1712-1721 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

The Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture was founded in the mid-17th century. The first of its kind, this academy aimed to allow all artisans—not just those unfairly favored by an archaic guild system—to work as professional artists. Prominent figures like court painter Charles Le Brun and courtier Martin de Charmois proposed this idea to King Louis XIV, who gave his approval in 1648.

Like the academies that would follow—including the Académie Royale de Danse (“Royal Academy of Dance”) in 1661; the Académie Royale des Sciences (“Royal Academy of Sciences”) in 1666; and the Académie Royale d'Architecture (“Royal Academy of Architecture”) in 1671—the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture sought to find and foster potential.

In order to achieve this elite objective, the academy began hosting a periodic Salon.

The Official Salon

Jean-André Rixens, “Opening day at the Palais des Champs-Élysées,” 1890 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

While the event's inclusivity increased over the years (in 1791, sponsorship switched from royal to government bodies, and, by 1795, submission was opened to all artists), its jury (established in 1748) rarely broke from tradition. When selecting artwork, for example, they favored conservative, conventional subject matter—including historical, mythological, and allegorical scenes as well as portraiture—rendered in a realistic style.

The Academy's traditional taste was overwhelmingly accepted until the 19th century, when an increasing number of European artists began embracing the avant-garde. While the Academy would reject most modernist pieces, some famously managed to secure a spot, including Édouard Manet's nude Olympia in 1863 and John Singer Sargent's Portrait of Madame X, a contemporary portrait exhibited in 1884.

For the most part, however, pieces that did not adhere to the academy's traditional tastes were rejected, forcing forward-thinking artists to take the exhibition of their work into their own hands. This led to the decline of the Paris Salon in the 1880s, and, most importantly, culminated in a new tradition: Salon alternatives.

Important Offshoots

“Caricature on Impressionism, on occasion of their first exhibit,” 1874 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Salon des Refusés

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, “The Luncheon of the Boating Party,” 1880-1881 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

“Numerous complaints have come to the Emperor on the subject of the works of art which were refused by the jury of the Exposition,” his office said. “His Majesty, wishing to let the public judge the legitimacy of these complaints, has decided that the works of art which were refused should be displayed in another part of the Palace of Industry.”

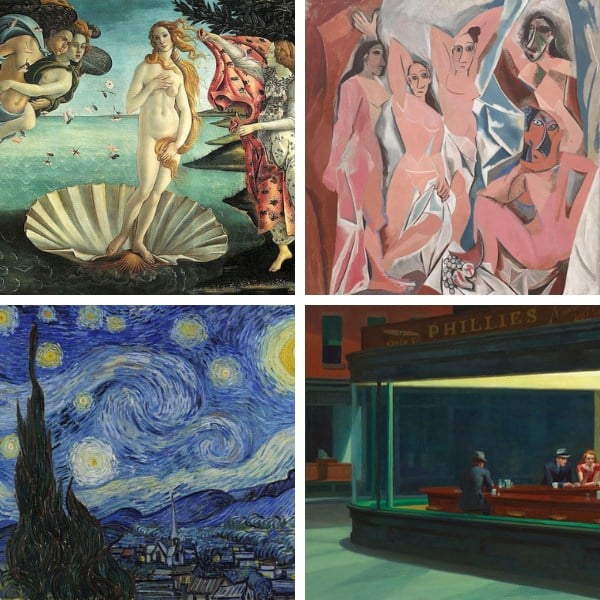

While originally mocked by the mainstream, today, many pieces presented in the Salon des Refusés are considered masterpieces, including Symphony in White, No. 1 by James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Le déjeuner sur l'herbe (“The Luncheon on the Grass“) by Manet.

Impressionist Exhibition of 1874

Claude Monet, ‘Impression Sunrise,' 1872 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Set in the studio of Nadar, a contemporary French photographer, this exhibition comprised several paintings by 30 artists, including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro. Among these works was Monet’s Impression, Sunrise, a landmark landscape painting that inspired the movement's name.

The Impressionists would continue to hold annual and biennial exhibitions until 1886. Key pieces exhibited in this string of shows include Le bal du moulin de la Galette (“Dance at the Moulin de la Galette”) and Le déjeuner des canotiers (“The Luncheon of the Boating Party”) by Renoir; Rue de Paris, temps de pluie (“Paris Street; Rainy Day”) by Gustave Caillebotte; and Seurat's Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte (“A Sunday on La Grande Jatte”).

Salon des Indépendants

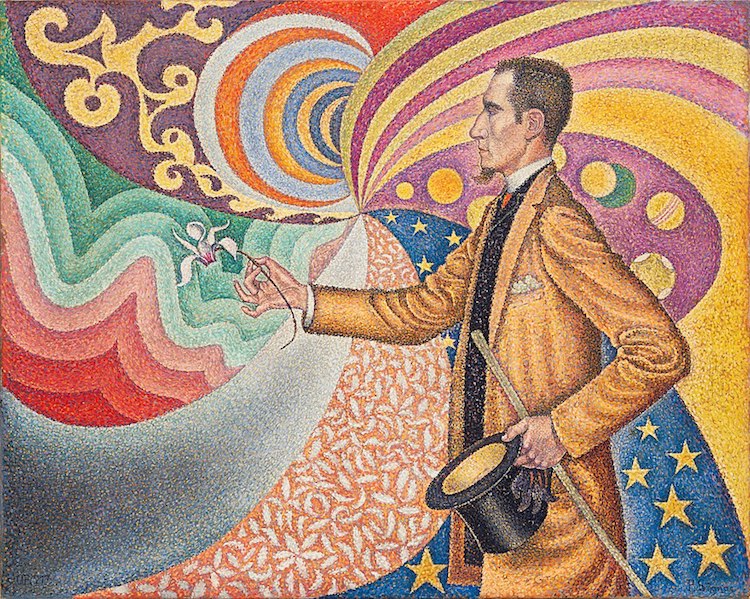

Paul Signac, “Opus 217. Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones, and Tints, Portrait of M. Félix Fénéon in 1890,” 1890 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Even without an incentive, artists flocked to have their work featured in this radical show. In its inaugural event alone, 5,000 works from over 400 creatives were exhibited. Over the course of its 134-year history, the Salon des Indépendants has featured highlights ranging from Paul Signac's Opus 217. Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones, and Tints, Portrait of M. Félix Fénéon in 1890 to Henri Matisse's Le bonheur de vivre (“The Joy of Life”).

Salon d'Automne

Henri Matisse, “Woman with a Hat,” 1905 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

The first Salon d'Automne was held in 1903. This show was met with positive reviews, prompting annual shows to continue indefinitely. Throughout its 117-year history, the Salon d'Automne has featured acclaimed works that have helped pioneer entire movements, with Fauvism and Cubism at the forefront.

Along with the even older Salon des Indépendants, the Salon d'Automne proves both the lasting legacy—and the staying power—of the subversive salon.

Related Articles

5 Must-See Museums in Paris (That Aren’t The Louvre or Musée d’Orsay)

How “La Belle Époque” Transformed Paris Into the City We Know and Love Today

Unraveling the Mystery of Avant-Garde Art

6 Facts About Gertrude Stein, One of Modern Art’s Most Important Collectors