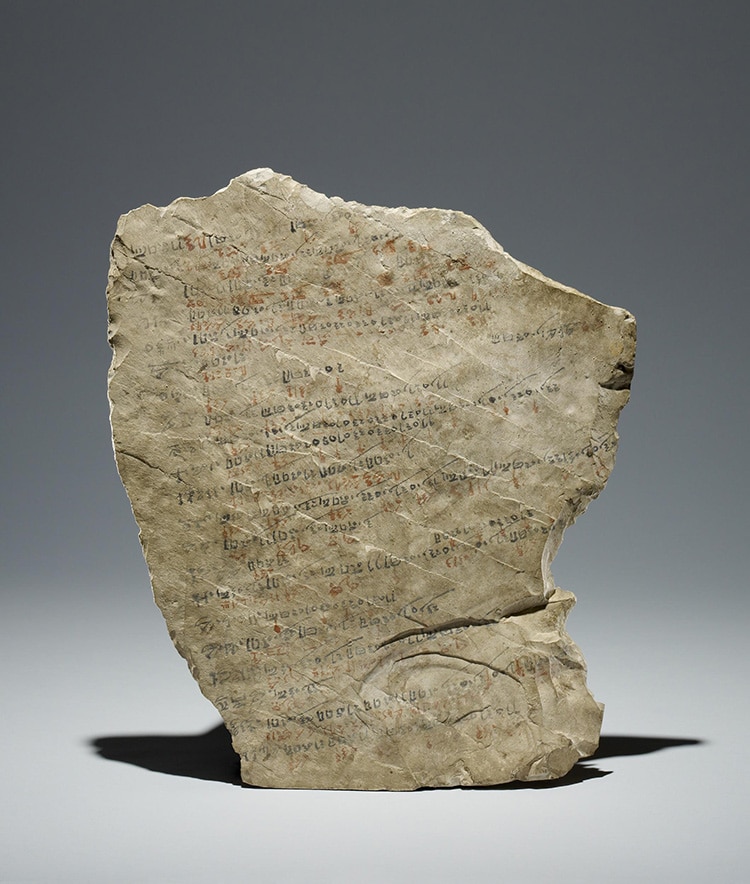

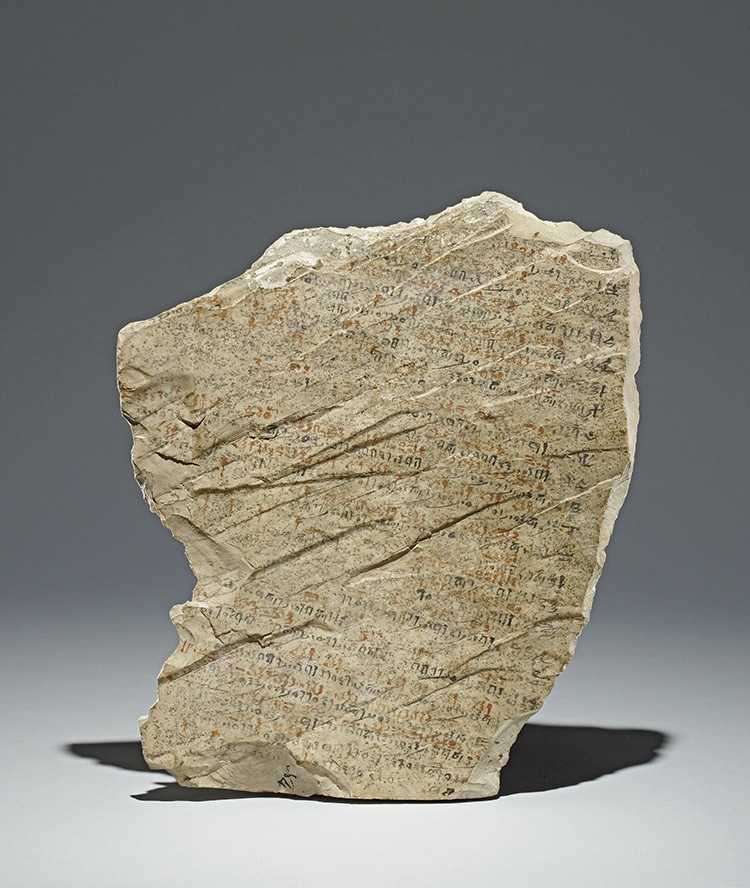

A limestone ostracon, listing workers and their reasons for being absent on certain debates, mark dLabelled ‘Year 40' of Ramses II, circa 1250 BC. (Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Calling in sick to work is apparently an ancient tradition. Whether its the sniffles or a scorpion bite, somedays you just can't make it. As it turns out, Ancient Egyptian employers kept track of employee days off in registers written on tablets. A tablet held by The British Museum and dating to 1250 BCE is an incredible window into ancient work-life balance. The 40 employees listed are marked for each day they missed, with reasons ranging from illness to family obligations.

The tablet, known as an ostracon, is made of limestone with New Egyptian hieratic script inked in red and black. The days are marked by season and number, such as “month 4 of Winter, day 24.” On that date, a worker named Pennub missed work because his mother was ill. Other employees were absent due to their own illnesses. One Huynefer was frequently “suffering with his eye.” Seba, meanwhile, was bit by a scorpion. Several employees also had to take time off to embalm and wrap their deceased relatives.

Some reasons may seem strange to modern ears. “Brewing beer” is a common excuse. Beer was a daily fortifying drink in Egypt and was even associated with gods such as Hathor. As such, brewing beer was a very important activity. Fetching stones or helping the scribe also took time in the workers' lives. Another reason is “wife or daughter bleeding.” This is a reference to menstruation. Clearly men were needed on the home front to pick up some slack during this time. While one's wife menstruating is not an excuse one hears nowadays, certainly the ancients seem to have had a similar work-life juggling act to perform.

The Ancient Egyptians kept track of work absences, and the reasons range from embalming relatives to brewing beer.

Related Articles:

Ancient Egyptians Were Cat People: Exploring Felines and Gods in Art and Culture

3,400-Year-Old Ancient Egyptian Painting Palette Still Contains Remnants of Pigments

11 Facts About the Ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertiti

Ancient Egyptian Coffins Sealed 2,600 Years Ago Are Opened for First Time in History