Telephone switchboard in the BK2 offices.

On April 26, 1986, an uncontrollable nuclear reaction began in the No. 4 reactor of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in what was then the Soviet-controlled Ukrainian SSR. The meltdown quickly became the worst nuclear power disaster in history—only the Fukushima Daiichi disaster in Japan in 2011 would reach the same level of destruction and contamination. Today, the site sits within an exclusion zone of 19 miles in any direction. Polish photographer and filmmaker Arkadiusz Podniesiński has spent over a decade documenting the ravages of the nuclear meltdown and the ongoing containment efforts. His images are haunting portrayals of one side of nuclear power.

Podniesiński first began photographing Chernobyl in 2008. Since his earliest trip to the site, he has seen the continual progress of containment efforts. This includes the building of a New Safe Confinement building around the highly radioactive remains of the No. 4 reactor. Although the exclusion zone now welcomes some tourists, Podniesiński has built relationships at the plant and is able to access spaces deep within the plant that few eyes will ever see. He has to check in with security and be lead by an expert guide. He carries devices to measure levels of radioactivity and wears protective gear. However, nothing can truly protect from the intense radiation in the depths of the old sarcophagus of reactor 4.

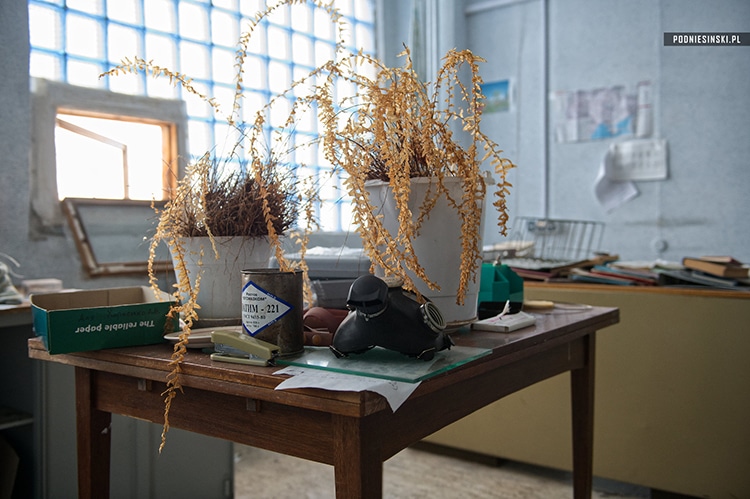

Podniesiński's images include a glimpse of the abandoned debris that remains much the same as it was left in the late 1980s when the plant was evacuated. In offices such as BK2, porcelain tea sets and archaic telephone equipment lie abandoned. The photographer also provides an instructive look at the management of the nuclear fuel and waste that remains at the site. This ongoing project involves decommissioning and processing fuel in special, delicate processes. Some rooms used in this process are too dangerous even for humans to enter; instead, machines are operated from remote control rooms. In Podniesiński's photographs, the post-meltdown plant is a fascinating yet dangerous place.

Podniesiński has created a two-part documentary film on Chernobyl—Alone in the Zone (2011, 2013)—which explores the evolving conditions of the site and the lives of those who live around it. He also published the photo album HALF-LIFE: From Chernobyl to Fukushima (2018) with photos and essays on the Chernobyl and Fukushima disasters. His other photographic projects range from documenting shipwrecks to photographing local religious practices in Africa.

My Modern Met had the chance to catch up with Podniesiński and speak about his work documenting Chernobyl. read on for the exclusive interview. For more technical information on Podniesiński's journey through Chernobyl and how the plant operates, check out his article The Sarcophagus's Labyrinth.

The New Safe Confinement (NSC) surrounding the old sarcophagus, a center of serious radiation.

You have been photographing the Chernobyl area since 2008, specifically focusing on the buildings and those who live and work in the area. How would you say the physical environment has most changed over the past decade?

More than 35 years have passed since the greatest nuclear disaster in history. During this time, the abandoned and un-renovated buildings, from which more than 100,000 people were evacuated, have been slowly but surely decaying. The main cause, of course, is the passage of time and weather conditions such as snow, rain, frost, and dampness that gradually destroy the buildings’ steel and concrete structures. They undermine the foundations and damage ceilings, which then begin to crack, crumble and collapse. Several buildings have already fallen down, and others will meet a similar fate sooner or later.

Nothing can stop this process. Without human intervention, it reverts back to nature. Unnaturally tall trees begin to cover buildings. Entire houses are overrun with vegetation, which then invades their interiors and tries to take back what once belonged to them. It’s like a Ukrainian version of Angkor Wat. The passage of time is this place’s greatest enemy; the rest of the destruction comes at the hands of thieves, vandals, and tourists who are visiting the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone in increasing numbers.

The old sarcophagus inside NSC.

Inside the old sarcophagus.

You've described the stringent security measures you have to go through in order to access the site. Some areas where the old fuel is processed are encased in lead glass and concrete. Why are these measures so important?

Although the last reactor was shut down in 2000, the Chernobyl power plant is still a nuclear facility with the highest possible safety protocols. Spent nuclear fuel and other radioactive waste accumulated during the plant’s operation and decommissioning remains on site. Processing and storing this is not only dangerous to humans and the environment but there is the potential risk for its theft and use by terrorists. The demolition of the old sarcophagus and the removal of the spent fuel inside will also begin soon.

Work with such hazardous materials required the design and construction of completely new structures like the New Safe Confinement, which covers the old sarcophagus, or the designing of new machinery and equipment to make the processing of radioactive materials possible at all. A major role was played in this by many European countries—including France—which not only financed construction but also led it.

Checking radiation levels.

An abandoned electronics workshop in Chernobyl.

You encounter a lot of radiation photographing sites of nuclear meltdowns. Do you take precautions for your camera equipment?

A camera is just an ordinary inanimate object, fairly easy to protect from radioactive dust—you clean it when it gets dirty or eventually buy a new one.

How do you know when to turn around, or if a particular area is too dangerous?

I pay much more attention to my own safety. That’s why when photographing the most radioactive places I always wear a protective suit and mask that prevents me from inhaling the radioactive dust. This type of protection, however, cannot protect me from gamma radiation penetrating my body. You will not see, hear, or smell radiation. That’s why I always carry a dosimeter with me in such places. It acts as my eyes; thanks to it, I know how far I can go, how close I can get, or for how long I can stay. In the most radioactive places, where radiation levels are tens of thousands of times higher than normal, that’s usually no longer than one minute.

The underground bunker in BK2.

You mention your camera has captured “bright spots” of invisible radiation. Can you share an example of an image like this?

The full report from my visit is available on my website. In the end, I posted an uncompressed, high-resolution photo where my camera sensor registered invisible radiation in the form of small, bright dots. The link to the photo is here. (Zoom in to see the spots using the link, the relevant image is below).

The camera appears to capture “spots” of invisible radiation in a high-risk zone.

Smashed office clocks in BK2 office.

Your book HALF-LIFE: From Chernobyl to Fukushima (2018) examines the political and environmental impact of nuclear disaster through essays and photos. What—in your opinion—is the most important thing governments should remember when working with nuclear power?

I would like to convey that despite the fact that nuclear catastrophes like Chernobyl in 1986 and Fukushima in 2011 are very rare and the likelihood of them occurring is infinitely small—when they happen, the political, economic, and human costs can be too high for society to absorb.

Porcelain left over inside the power plant.

Any books or films coming soon?

My first album HALF-LIFE: from Chernobyl to Fukushima, where I documented the destruction caused by the disaster, took over 10 years to write. Currently, I’m working on the second part of the album in which I’d like to focus on the reconstruction of these areas and the return of residents as well as the process of decommissioning the power plant. Unfortunately, as we know, it’s an incredibly complicated and time-consuming process, so the second album won’t be made anytime soon.

An office in BK2, Chernobyl.

A storage room in BK2.

An interim facility for storing spent nuclear fuel.

The fuel extraction room.

Interior of the hot chamber, where no human can go.

Control panel looking into the hot chamber where fuel is processed.

Spent fuel assemblies.

Storage for empty radioactive waste containers.

Concrete-encased storage for fuel canisters.

Arkadiusz Podniesiński: Website | Facebook

My Modern Met granted permission to use photos by Arkadiusz Podniesiński.

Related Articles:

Photographer Documents the Otherworldly ‘Mutant Vehicles’ That Inhabit Burning Man [Interview]

Surfing Photographer Captures the Timeless Beauty of Cresting Ocean Waves

Amazing Restored Photos of Earth Taken by Apollo Astronauts

Before and After Photos Reveal How Much a Smile Changes a Person’s Aura [Interview]