For over 10 years, sculptor Jason deCaires Taylor has dedicated his artistic practice to the enhancement and conservation of the underwater world. He has created underwater museums in Europe and spread his art throughout the Caribbean, and his latest project takes him to the Earth's most famed marine ecosystem.

Australia's Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef and, now, Taylor will have a part in raising more awareness about its beauty thanks to his work with the Museum of Underwater Art (MOUA).

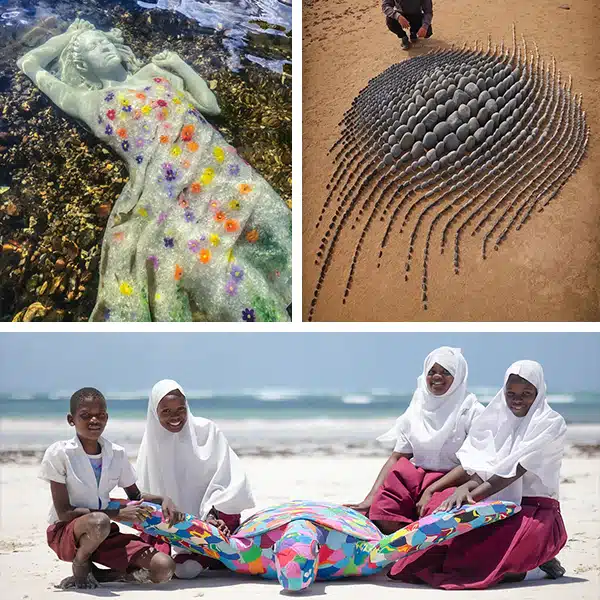

In collaboration with scientists at James Cook University and the Australian Institute of Marine Science, Taylor spent years gaining permissions to install the first artificial reef in these waters. The result is Coral Greenhouse, a collection of hyperrealistic underwater sculptures inspired by the community's youth. It's these young people that Taylor hopes will become engaged and take their role as the future conservators of this precious ecosystem seriously.

This work is coupled with Ocean Siren, an interactive sculpture that stands as a beacon just beyond Townsville's Strand Jetty. Rising from the water, the figure was modeled after 12-year-old Takoda Johnson, a local indigenous girl from the Wulgurukaba tribe whose families once owned local lands. The sculpture changes color in conjunction with the ocean's temperatures and was made possible by close collaboration with scientists.

In merging art, science, and conservation, the Museum of Underwater Art wants to bring more people to these waters. And by increasing awareness about the Great Barrier Reef and the incredible coral that still thrives in many areas, they're hoping to inspire greater conservation efforts. Plans to build up the museum are ongoing. There are two further installations that Taylor will create for the project, though the initial portions of the museum should open to the public shortly.

We had the chance to speak with Taylor about this important project and his experiences with the local community. Read on for My Modern Met's exclusive interview.

You've worked in so many ocean environments. How was working in the Great Barrier Reef different?

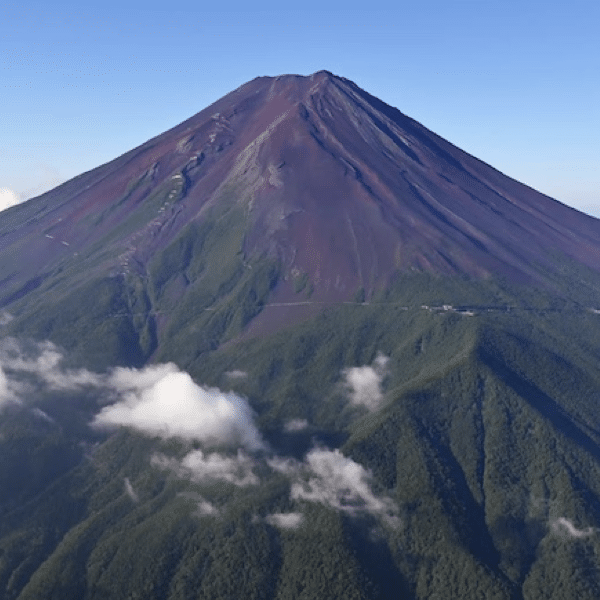

There are obviously many, many different things. It’s the first time I have really worked in the Pacific Ocean, and just the variety and the diversity of life there are some of the best in the world. The various different types of coral and marine species are so incredible—there are so many colors and forms and shapes. It was a huge privilege to work there, and it’s something that’s been a personal ambition of mine for quite some time.

The trajectory and ambition of the project were also very different. Previously, working in the Caribbean, there are not so many reefs. They’re smaller in scale and quite fragile. And the objectives have been about taking people away from natural areas and creating this artificial reef. Whereas working in the Great Barrier Reef, it’s such a vast structure and it’s so endless, there’s not a problem with over-tourism and high-impact numbers and you don’t need to divert people away from it. So, it had a kind of different objective.

It was more about getting more people to go and see it because it has experienced some bleaching over recent years, but mainly in the northerly parts, and two-thirds of it is still incredibly pristine and beautiful, but there’s this misconception that it’s dying or it’s already dead. That’s not the case. Actually the area where we built the museum has some of the best coral I’ve ever seen in my life, so we wanted people to see that and we wanted to help motivate people to want to conserve it.

How did the collaboration with the Museum of Underwater Art come together to begin with?

I first started in Townsville, Queensland, which is home to one of the largest marine research laboratories in the world—the James Cook University—as well as AIMS (Australian Institute of Marine Science). It is a real hub for science.

Local marine biologists Paul Victory and Adam Smith, who have been following my work for some time, were quite interested in how to communicate science better and in a more mainstream way. So, they first got in touch with me almost four years ago and it slowly developed from there. It’s been quite a lengthy project. Working on the Great Barrier Reef, we’ve had to do an incredible amount of research and the permitting application was one of the most complicated I’ve ever been part of. It was something relatively new for the authorities, so it’s taken three years to get to this point.

It's interesting that the project was kicked off by scientists. Obviously your work mixes art and science quite a bit. This is particularly evident here with the Ocean Siren sculpture that greets people in Townsville. How did that concept come together?

I’ve very much been interested in ways to tell stories about the marine environment online and in urban environments—bringing it into the kind of spaces where people aren’t really connected to the ocean. And I really like this idea that something that was happening underwater, far outside the Great Barrier Reef but could be felt in real-time and witnessed by everybody.

How did you work with scientists to bring your vision to life?

It’s actually an idea I’ve had for some time, but I’ve not been able to implement it just because I haven’t found the right location and the technical aspects were quite complicated. But, obviously, Townsville was the perfect place because there are already weather stations positioned on lots of different parts of the Great Barrier Reef and these stations monitor water temperature, salinity… lots of different metrics. So it was actually possible for me to be able to do that by working with AIMS Institute to connect that data and then share it on the sculpture.

It's really wonderful because, as you said, sometimes it's difficult for people to make sense of this intangible data, and with the sculpture, they're able to visually see what's happening below the surface in a quite beautiful way.

I was really inspired by a quote by Gus Speth, U.S. Advisor on Environment and Climate Change: “I used to think that the top environmental problems were biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse, and climate change. I thought that 30 years of good science could address these problems. I was wrong. The top environmental problems are selfishness, greed, and apathy, and to deal with these we need a cultural and spiritual transformation. And we scientists don’t know how to do that.”

I think the world’s changed in the last few years and where you would think that common sense or logic and facts would prevail, they haven’t. You could argue that people are much more swayed by emotional and spiritual arguments than they are behind facts and figures.

Certainly, the visual arts have the ability to tap into people’s emotions and perhaps cause them to get more involved with a social cause they might never have cared about otherwise. I know you tried to engage the public when you did workshops with the local community. How did those turn out and did you achieve that you expected?

So most of the models for the projects I have completed are part of community workshops. I feel that’s a really important part of the process. The local community becomes the sculptures; they become ambassadors or guardians for the reef. And I think that’s really critical for them, especially children growing up. They feel like they have a sense of ownership and a sense of responsibility to protect the reef.

In Australia, I really wanted to make sure that the indigenous community was represented in the artworks. So it was very important to get the local community to join in and be part of it. In fact, Ocean Siren was a young indigenous girl whose family are the traditional owners of the land. She looks out to sea, and she also looks out on the island of her great grandfather.

How did the overall vision for Coral Greenhouse come together?

One of the overriding objectives was that we wanted young people to be inspired by marine science and fascinated by it. And want to have an active interest in the health of the reef and to be able to explore it in a fun and dynamic way.

One of the big objectives was to create this space encompassing many areas, to be not only a space for art and culture but only about marine science and to use it as a portal or access point to explore the Great Barrier Reef.

Photo: Richard Woodgett

So you've already mentioned that the permitting was a big hurdle. But that aside, what were some of the other challenges you faced with this installation?

Yeah, it was pretty difficult. There are many, many factors. One of them being the occurrence of big cyclones on the Great Barrier Reef. So you had to plan the structures for a category four cyclone and that was very challenging—very difficult to do, especially with the scale of the project.

It’s also, I think, around 70 kilometers (43 miles) away from the shore, which is a very long way, especially when you’re towing hundreds of tons of artwork. It took us 16 hours to get there.

So there were some challenges, but there were also some very helpful things. I was very lucky in Australia to have incredible logistical help, the operators there—the machinery and the cranes—the experience there is really second to none. It has a very rich diving history. So I was fortunate in many respects.

Photo: Richard Woodgett

So for people who may not understand how these things work, can you share a bit about how these installations end up providing a good habitat for marine life?

Sure. So take the Coral Greenhouse, for instance, this is situated on a patch of sand in a kind of underwater channel at the northern part of the reef. It is flushed by a nutrient-rich current which is an ideal area for corals and marine life to flourish.

Because the sculpture is quite high, it spans all different areas of the water column. And so, in the lower parts, we have all these different habitat spaces for marine life. This includes a series of workbenches and modules which have a different type of hollowed space tailored for different types of creatures. So some of the holes are very small and just allow juvenile fish to get inside and be protected. Some of them are much larger for crustaceans and larger species. And so all this area beneath the lower end, it creates this artificial reef habitat—an area for fish to spawn and to take refuge.

Then, as the structure moves up, it starts to go into the kind of high current area where there’s a lot of nutrients flowing through the water. And from that part, it offers a really good substrate for all the different species that are filter feeders that extract all the nutrients from the water. So all the different types of hard and soft corals or crinoids, they can all attach to the structure and start sieving it for food. It becomes a large tree community. The smaller species very quickly attract larger species that then predate on them so, in a very short space of time, you get a very healthy reef system revolving around it.

What do you hope that people take away from your work at the museum in Australia?

First of all, I hope the people who come to Townsville make the trip out and go to see the Great Barrier Reef in itself. Where it’s positioned, as I mentioned, it’s actually next to some of the most spectacular reefs I’ve seen. So I hope that people go out there and snorkel and dive and see how incredible the reef is and how beautiful and diverse it is, and also get to see how we can actually live in some kind of symbiotic relationship in harmony with nature. It’s not a matter of us being conquerors of the natural world, it’s much more about interconnectedness. I hope people leave with that kind of sense.

Photo: Richard Woodgett

So I know that things might be on pause at the moment, but what's next for you?

I was in mid-roll with a few different projects. For instance, the Australia project wasn’t finished so I still have to return. And we are in the process of installing, I think, 4,000 corals into the greenhouse. We also want to expand the project into a Palm Island, which is a very beautiful Island just off the coast and is home to a large indigenous community. The idea is to create some large scale artworks for the community whilst helping to provide more local jobs and economic stimulus. We’ve been planning this for the last two years and we’ve raised the finances for it. We’re in the process now of just deciding the design with the local community. There are actually four phases to the Australia project. We finished the first two, so we’ve still got another two to go.