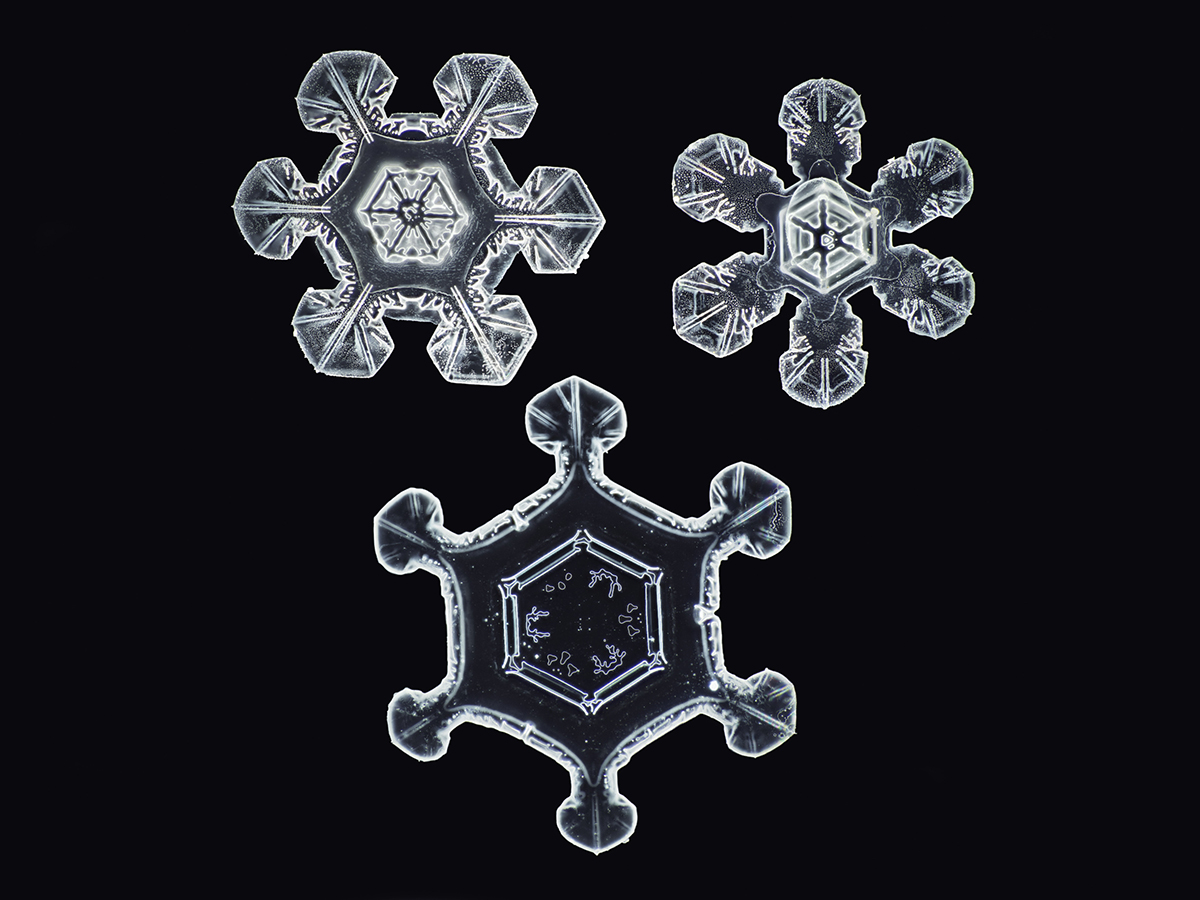

“No Two Alike” by Nathan Myhrvold

Everyone knows that snowflakes are unique arrays of tiny crystals—no two are precisely the same. However, capturing the unique designs of snowflakes using photography can be very tricky. Snowflakes are easily disfigured with the slightest warmth or touch, so renowned photographer Nathan Myhrvold had to develop a specialized camera when he decided to shoot the most technically advanced images of snowflakes ever attempted. As a photographer, chef, and founder of Modernist Cuisine, Myhrvold's years of experience in food photography prepared him with the speed, innovation, and technical skill for this challenge. With his purpose-built camera, he captured stunning images of delicate snowflakes at the highest resolution to date.

To get these perfect shots—available now as prints at the Modernist Cuisine Gallery—many factors had to be perfectly calibrated. To avoid melting or sublimation of the snowflakes, the images were shot on location in Fairbanks, Alaska and Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada. Myhrvold used a special camera of his own design. He combined the magnifying power of a microscopic lens (as typically used in snowflake photography) with a specially designed optical path. This path allowed the lens to channel its image to a medium-format digital sensor—which provided the stunningly high level of resolution. In addition, the camera featured a cooling stage upon which the tiny specimens could rest. With LED short-pulse lights and a shutter speed of less than 500 microseconds, Myhrvold was able to capture multiple images of each snowflake at different focal lengths. These images were then stacked to create the final image.

The scientific precision which enabled Myhrvold to create this unique snowflake camera is a hallmark of his varied career. With a PhD in Physics from Princeton, as well as two master's degrees, he did his postdoctoral research on quantum field theory with Stephen Hawking at Cambridge University. The young scientist then began his own software company, before working for Microsoft as chief technology officer alongside founder Bill Gates. He left the software world in 1999 to focus on food and photography—two of his lifetime interests. Founding Modernist Cuisine and authoring multiple cookbooks, Myhrvold merges his scientific knowledge with photographic skill and renowned recipes. His cookbook photography is shown in his four galleries, as well as through traveling installations around the world. It is not often an artist can claim physics research with Stephen Hawking alongside multiple James Beard Awards. Throughout his career, Myhrvold has taken innovation to the next level—his new snowflake images are no exception.

My Modern Met had the opportunity to catch up with Nathan Myhrvold to discuss his snowflake images—which depict nature's marvels in the highest resolution photographs yet taken. Scroll down to hear about this innovative photographer's thoughts and process.

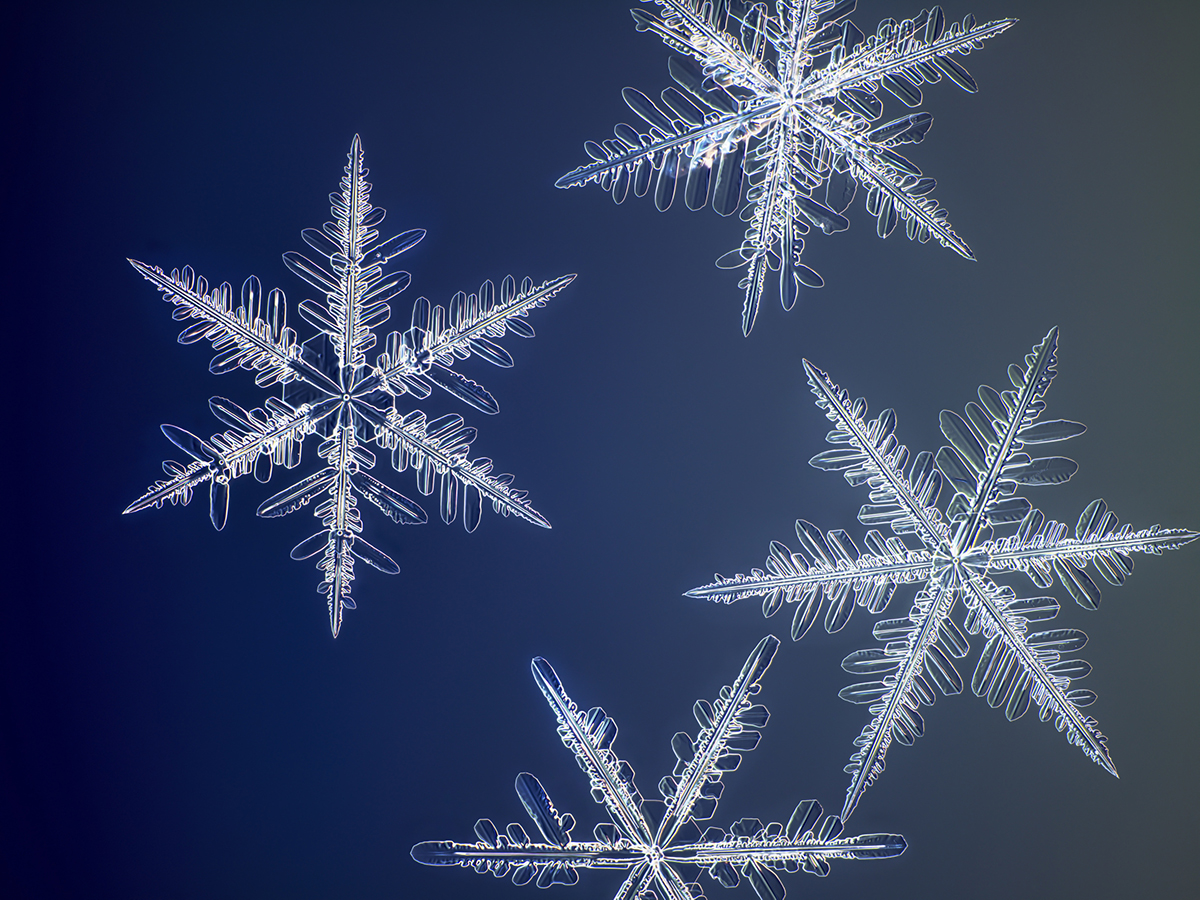

“Yellowknife Flurry” by Nathan Myhrvold

What is it about snowflakes that you find inspirational as a photographer?

Water, an incredibly familiar thing to all of us, is quite unfamiliar when you see it in this different view. This makes snowflakes a great example of hidden beauty. Their intricate beauty is derived from their crystal structure, which is a direct reflection of the microscopic aspects of the water molecule.

Did you start the project with the idea of having to build a custom camera or did that necessity become apparent once you started?

I do a lot of research before starting a project, so I went into it knowing that I would have to customize most of the setup.

How long did it take to build the camera and what was the biggest challenge in doing so?

It took 18 months to design and custom-build the Snowflake Cam. One of the biggest challenges is that snowflakes are only a few millimeters across, so they present a challenge to photograph due to their size and fragility.

I had to figure out a way to keep the snowflakes from melting or vaporizing too quickly because the sharp features of their crystal structure degrade over time. To address this issue, I added a cooling stage to the microscope as well as pulsed high-speed LED lights, which reduced the heat emitted from the microscope. This helped prolong the time that the snowflakes remained frozen and gave me more time to photograph and focus-stack the images.

How long does an average shoot in the field take and what research goes into things before you head out into the field?

Location scouting is very important for field shoots. For these photos, temperature was the main factor for determining location in addition to considering wind, moisture, and humidity. Different conditions result in different snowflakes, so once the weather shifts, it may no longer be ideal for photographing snowflakes. When it is warmer, the snowflakes tend to clump, and when it is colder, they tend to dry out. Some of the best snowflakes that I found were at temperatures between -15°F and -20°F (-26°C to -29°C).

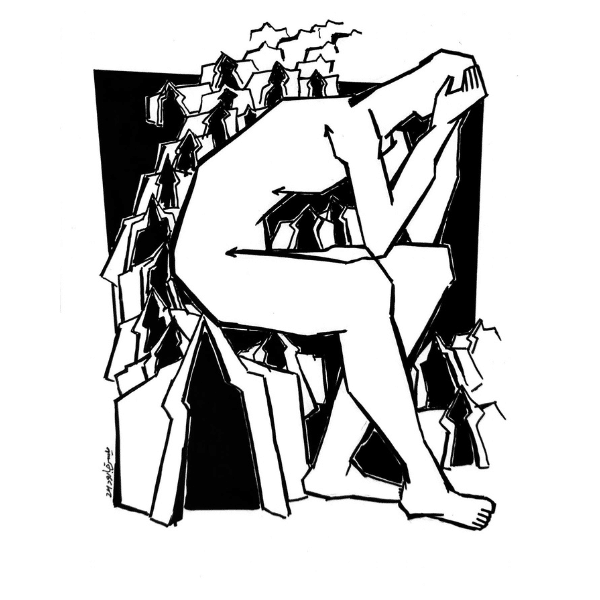

“Ice Queen” by Nathan Myhrvold

What’s surprised you the most about what you’ve discovered while photographing snowflakes?

I never cease to be surprised by the beauty and complexity of snowflakes. A snowstorm can go on for five hours, and if you’re out there with a piece of foam core trying to catch snowflakes, what’s amazing is that they can change minute by minute, right before your eyes, and there’s billions of them. Most snowflakes, numerically, are not perfect dendrite beauties; they’re a fairly simple hexagonal rod or plate. That can change extremely suddenly, though, and that’s when you go from boring plates to seeing something amazing. So you have to quickly mobilize to get the shot.

Some of the snowflakes in my photos, for example, are symmetrical star-shaped crystals called stellar dendrites. These types of snowflakes are dendritic, meaning that each of the arms keeps growing and nucleates more and more arms. All this happens because water molecules want to form hexagonal crystals. In the environment where snowflakes form, you get some event that starts a little plate. Other water molecules want to join, but they only want to join where they can make this hexagonal pattern. This stellated dendrite process only happens when it’s about 5°F (-15°C).

What do you hope that people take away from these images?

I wanted to show people the hidden beauty of snowflakes at a new level of detail and clarity. I hope people can tell there’s beauty in things that they can’t see with the naked eye.

“No Two Alike” by Nathan Myhrvold, displayed as a print available from Modernist Cuisine Gallery.