Photo: Stock Photos from dibrova/Shutterstock

Washington, DC is a treasure trove of American history. While much of the capital city serves as an archive of the past, the National Mall stands above the rest. This nearly two-mile stretch of land is lined with some of the country's most prized museums and monuments, from a string of Smithsonians to the Lincoln Memorial.

The historical significance of the Mall, however, is marked by more than the landmarks it houses. Spanning over 200 years, the history of the National Mall itself is worth exploring. Here, we stroll through a meandering timeline of the important site, from its original plan to its current state as the “monumental core” of the capital—and country.

A “Grand Avenue”

Allyn Cox, Portrait of Pierre Charles L'Enfant in the US Capitol (Photo: Architect of the Capitol [Public Domain])

L'Enfant quickly became known for his creativity—both on and off the battlefield. On top of mastering the “art of fortification,” he was also recognized for his fine art skills; he was even reportedly commissioned to paint a portrait of George Washington in 1778. Merging these skill sets, L'Enfant pursued a career in civil engineering after the war, culminating in his most famous project: designing the new federal district.

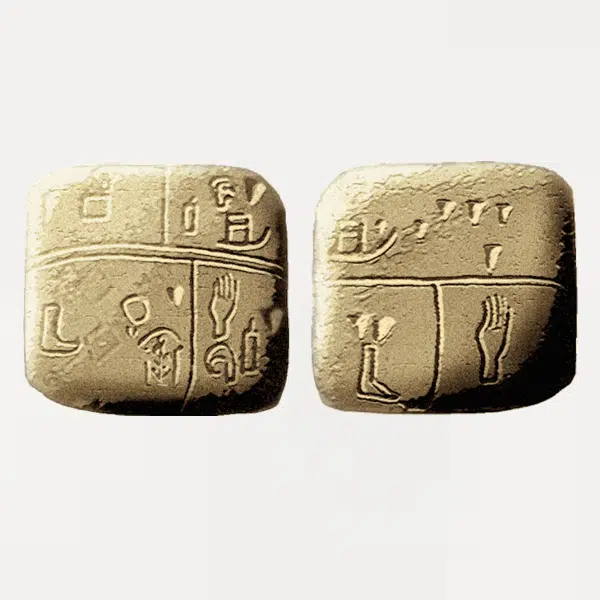

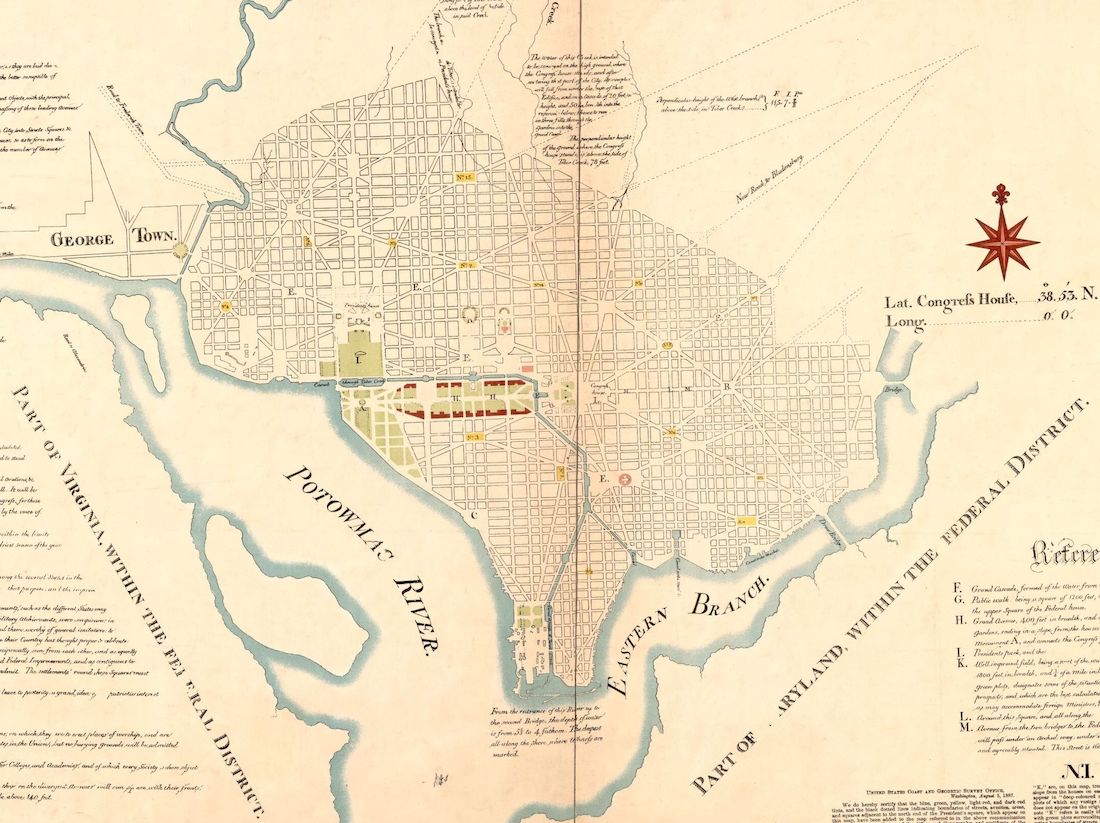

In 1791, George Washington appointed L'Enfant to come up with a plan for the “City of Washington.” While Washington and Thomas Jefferson, his Secretary of State, saw this as a modest task (they assumed he'd simply help them pick a location and the sites of important buildings), L'Enfant had bigger plans, as laid out in his Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of the United States.

Pierre Charles L'Enfant's 1791 Plan for the Federal Capital City (Detail) (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [CC BY 2.0])

Unfortunately, the overly ambitious nature of L'Enfant's plans strained his professional relationships, and, in 1791, he was dismissed by Washington. Land surveyor Andrew Ellicott took over the project, revising L'Enfant's plans until architect and horticulturist Andrew Jackson Downing was put in charge in the early 1850s.

A “Public Museum”

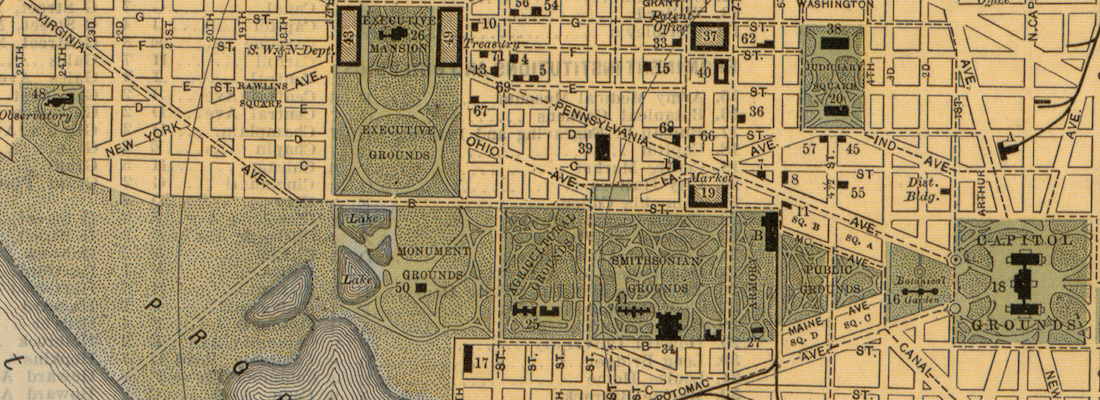

Map of the Mall in 1893 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Downing dreamt up a promenade with discrete naturalistic parks that would turn L'Enfant's manicured Mall into “a public museum of living trees and shrubs.” Facing limited resources, Congress initially only approved some of the project. And, by 1853—a year after Downing's untimely death—all funding was cut. Still, against all odds, his plan mostly managed to reach fruition. Over the coming years, public parks would pop up along the Mall and, following the Civil War, the space was even outfitted with greenhouses used to grow crops.

The “Monumental Core”

The McMillan Plan of 1901 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Chaired by James McMillan, a Republican Senator from Michigan, the McMillan Commission proposed a major Mall refurbishment to mark the city's centennial. In order to aptly commemorate this anniversary, the team looked to L'Enfant's “European” plan, culminating in a design typified by “a legal enforced height restriction, landscaped parks, wide avenues, and open space allowing intended vistas.”

This “open space,” however, would not be in the form of the “grand avenue” L'Enfant had envisioned. It would instead materialize as a tree-lined lawn framed by busy boulevards, flanked by celebrated buildings, and pierced by the Washington Monument, a 555-foot marble obelisk intended to honor George Washington. Dedicated in 1885, this structure remains an icon of what the McMillan Commission called the country's “monumental core”—even after an earthquake in 2011 called for its complete restoration.

The Mall Today

Stock Photos from S.Borisov/Shutterstock

Even prior to the earthquake, there had been an increasing emphasis on maintaining the Mall and its monuments. Since 2007, the Trust For The National Mall, a non-profit partner of the National Park Service, has worked to preserve the promenade, which sees over 36 million annual visitors.

What can sightseers expect at the Mall today? On top of a glimpse into L'Enfant's sprawling layout and Downing's dream of a “public museum,” the Mall's “open space” houses a wealth of world-class museums—from the Neo-Classical National Gallery of Art to the forward-thinking National Museum of African American History and Culture—as well as sculpture gardens and poignant memorials. A “masterful blending of formal history and tradition and informal contemporary life,” these sites make the historic Mall one of today's most important cultural destinations.

Related Articles:

D.C. Mayor Commissions Massive Black Lives Matter Mural on Street, Activists Add to It

25 White House Photos Highlighting President Obama’s Eight Years in Office