April 25, 1942—San Francisco, California. Residents of Japanese ancestry appear for registration prior to evacuation. Evacuees will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration.

Photographer Dorothea Lange is best known for her candid shots of the 1930s Great Depression and showing the heart-breaking struggle that many endured during that time. One of her most famous pieces from the period is the iconic Migrant Mother, in which a destitute pea picker is embraced by two of her seven children. In 1942, she was hired by the US government to similarly document the “evacuation” and “relocation” of Japanese-Americans. While opposed to the idea, she was eager to take the commission because she thought “a true record of the evacuation would be valuable in the future.”

Military commanders reviewed Lange’s work afterwards and were not pleased once they realized her contrarian view of the internment camps. They then seized the photos for the duration of World War II and deposited them in the National Archives, unavailable for view. In 2006, the censored pictures were finally released.

Lange’s heartbreaking photos show the different phases of the internment. She snapped portraits of Japanese-Americans as they wait to register before the “evacuation,” are bused to the camps, and then forced to establish a new routine in the meager and desolate parts of California. The effects—and despair—felt by those confined is palpable through these images.

The book Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment features quotes from those imprisoned. “We went to the stable, Tanforan Assembly Center. It was terrible,” one Osuke Takizawa recalled. “The Government moved the horses out and put us in. The stable stunk awfully. I felt miserable but I couldn’t do anything. It was like a prison, guards on duty all the time, and there was barbed wire all around us. We really worried about our future. I just gave up.”

In addition to her photographs, Lange meticulously captioned her photos, offering context to this troubling time. See a selection of her images (with the captions) below. Tim Chambers of Anchor Editions has also made a limited number of Lange’s prints available for sale.

Dorothea Lange captured a powerfully candid portrait of Japanese-American internment during World War II.

During registration:

San Francisco, California. Flag of allegiance pledge at Raphael Weill Public School, Geary and Buchanan Streets. Children in families of Japanese ancestry were evacuated with their parents and will be housed for the duration in War Relocation Authority centers where facilities will be provided for them to continue their education.

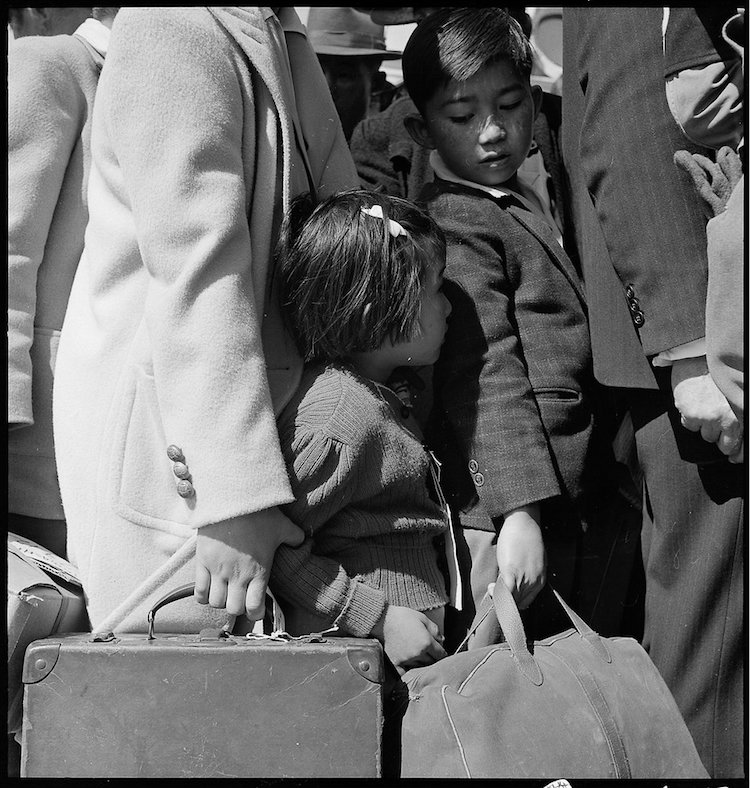

May 2, 1942—Byron, California. Third generation of American children of Japanese ancestry in crowd awaiting the arrival of the next bus which will take them from their homes to the Assembly center.

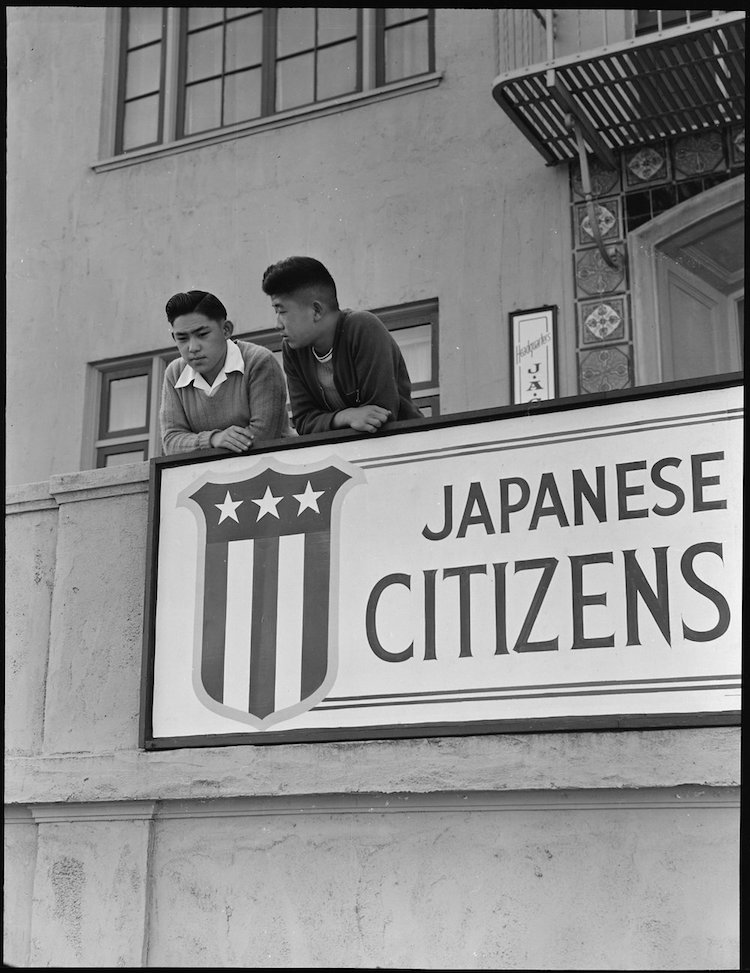

San Francisco, California. High school boys, on balcony of Japanese American Citizens League at 2031 Bush Street, look down sidewalk where friends boarded evacuation buses. Evacuees of Japanese ancestry will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration.

May 8, 1942—Hayward, California. Members of the Mochida family awaiting evacuation bus. Identification tags are used to aid in keeping the family unit intact during all phases of evacuation. Mochida operated a nursery and five greenhouses on a two-acre site in Eden Township. He raised snapdragons and sweet peas. Evacuees of Japanese ancestry will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration.

Sacramento, California. Rooming House in the Japanese section of town. Photograph taken two days before evacuation.

As Japanese-Americans left:

May 20, 1942—Woodland, Yolo County, California. Ten cars of evacuees of Japanese ancestry are now aboard and the doors are closed. Their Caucasian friends and the staff of the Wartime Civil Control Administration stations are watching the departure from the platform. Evacuees are leaving their homes and ranches, in a rich agricultural district, bound for Merced Assembly Center about 125 miles away.

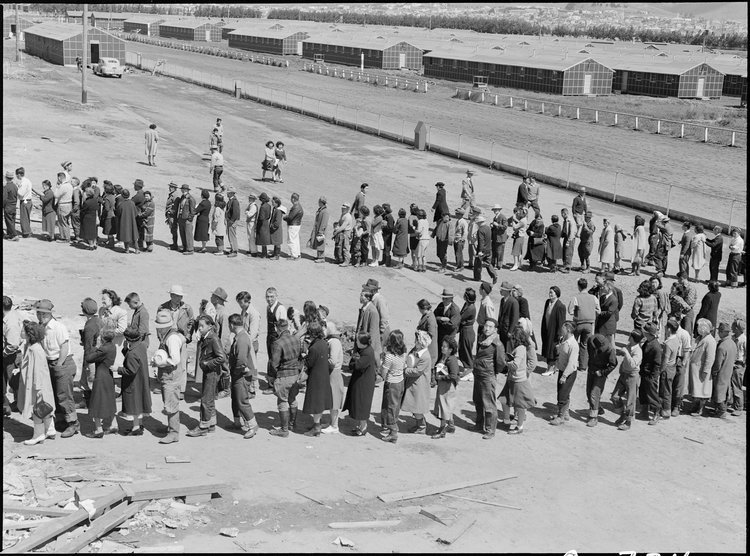

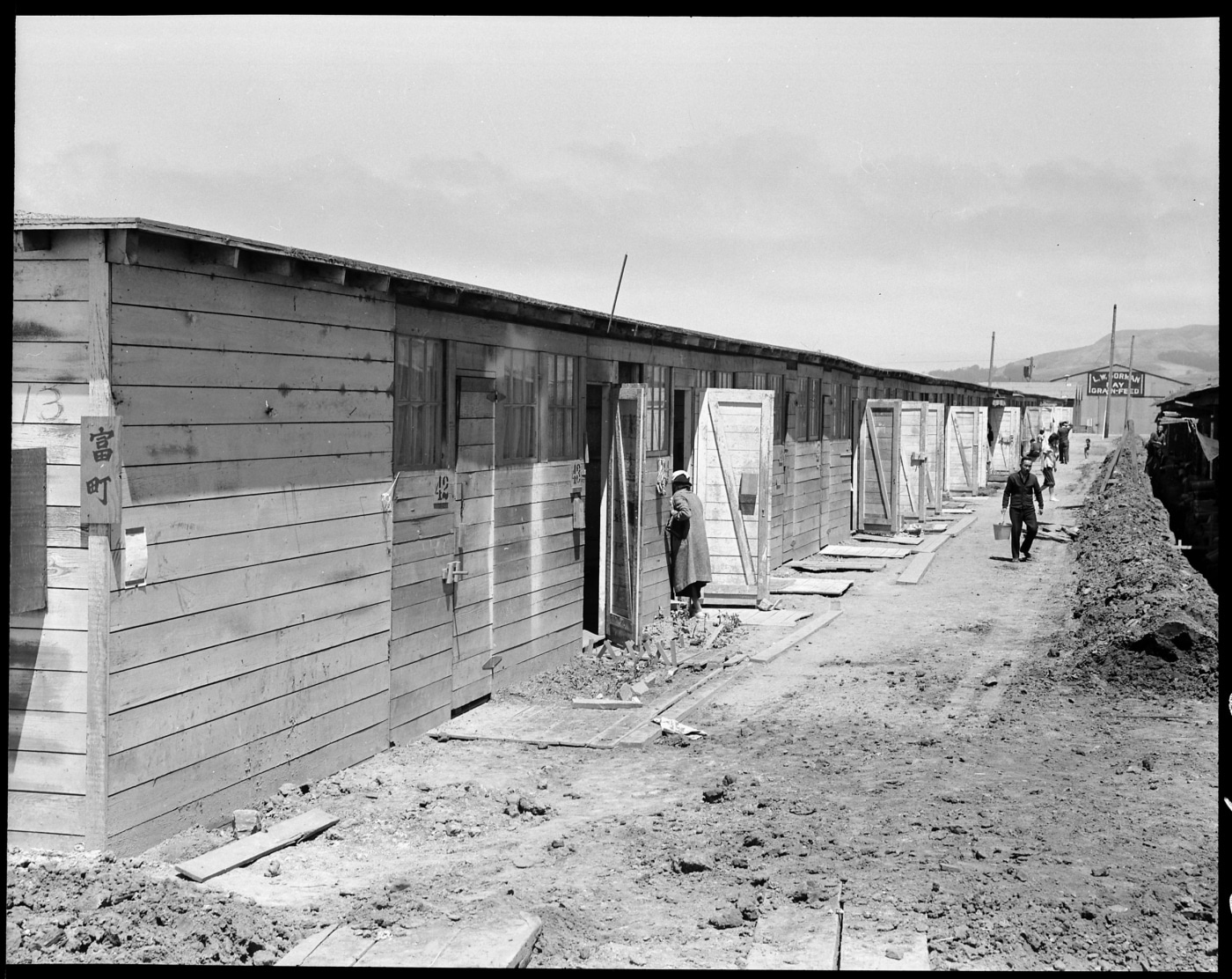

April 29, 1942—San Bruno, California. This assembly center has been open for two days. Bus-load after bus-load of evacuated persons of Japanese ancestry are arriving on this day after going through the necessary procedures, they are guided to the quarters assigned to them in the barracks. Only one mess hall was operating today. Photograph shows line-up of newly arrived evacuees outside this mess hall at noon. Note barracks in background, just built, for family units. There are three types of quarters in the center of post office. The wide road which runs diagonally across the photograph is the former racetrack.

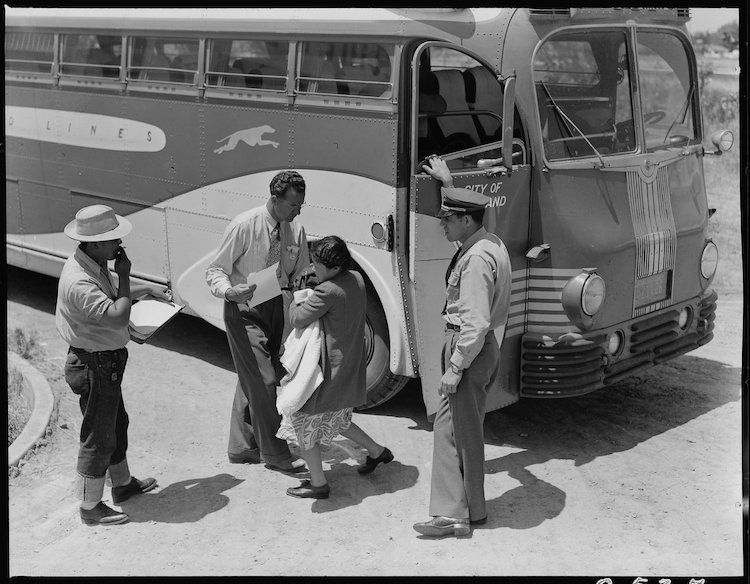

May 19, 1942—Stockton, California. Young mother of Japanese ancestry has just arrived at this Assembly center with her baby and she is the last to leave the bus. Her identification number is being checked and she will then be directed to her place in the barracks after preliminary medical examination.

While at the camps:

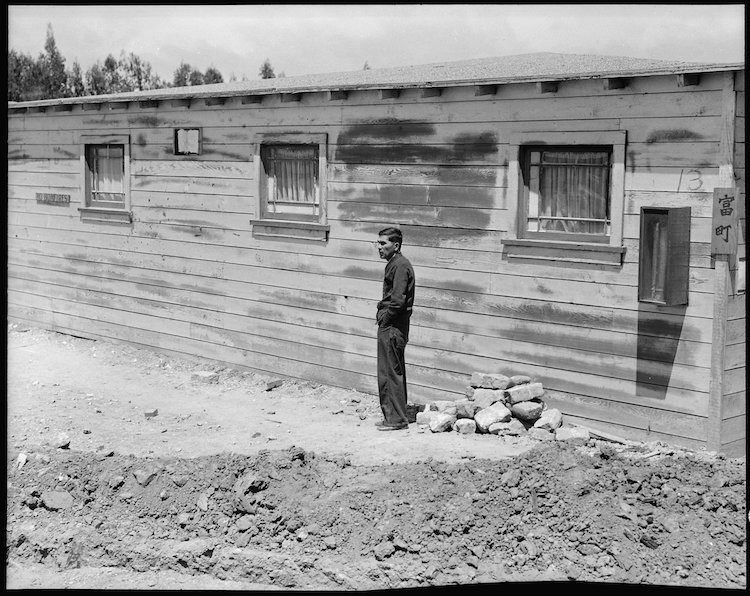

June 16, 1942—San Bruno, California. Many evacuees suffer from lack of their accustomed activity. The attitude of the man shown in this photograph is typical of the residents in assembly centers, and because there is not much to do and not enough work available, they mill around, they visit, they stroll and they linger to while away the hours.

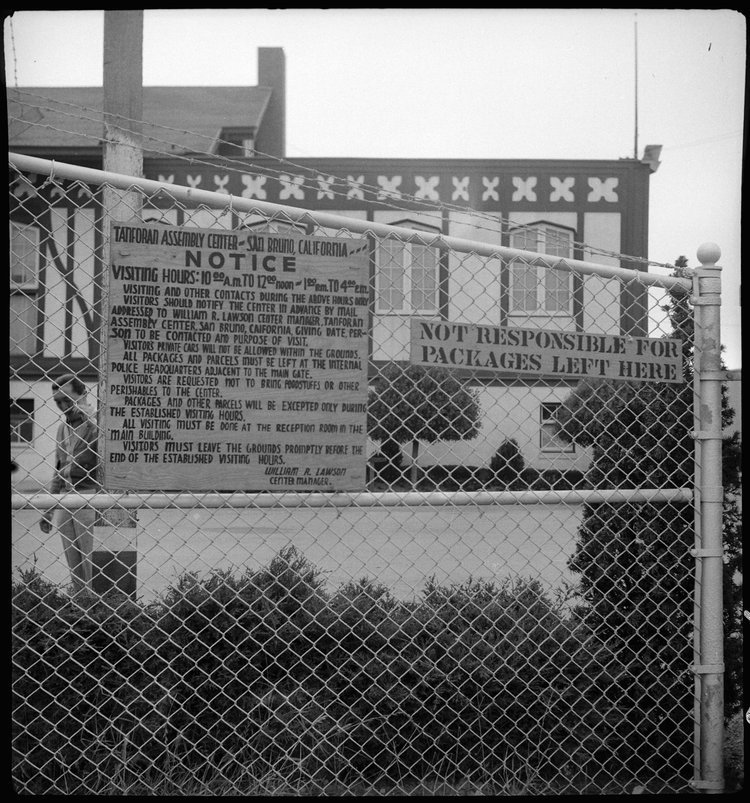

June 16, 1942—San Bruno, California. A sign at the main entrance of the Tanforan Assembly center, through which all traffic passes. The gate is guarded and controlled by United States soldiers.

June 16, 1942—San Bruno, California. This scene shows one type of barracks for family use. These were formerly the stalls for race horses. Each family is assigned to two small rooms, the inner one, of which, has no outside door nor window. The center has been in operation about six weeks and 8,000 persons of Japanese ancestry are now assembled here.

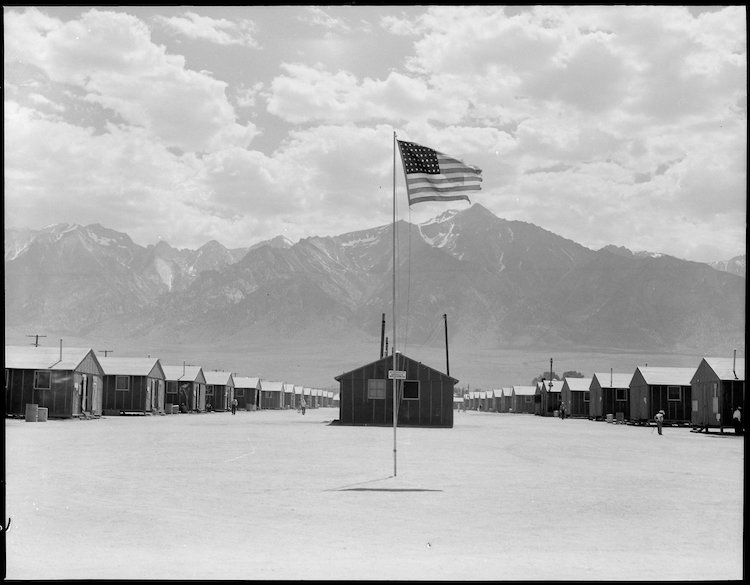

July 3, 1942—Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Street scene of barrack homes at this War Relocation Authority Center. The windstorm has subsided and the dust has settled.

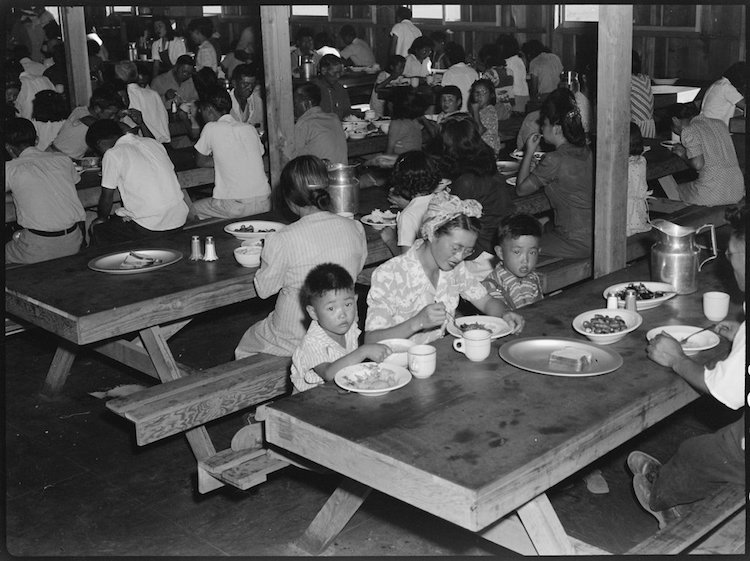

July 2, 1942—Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Mealtime in one of the messhalls at this War Relocation Authority center for evacuees of Japanese ancestry.

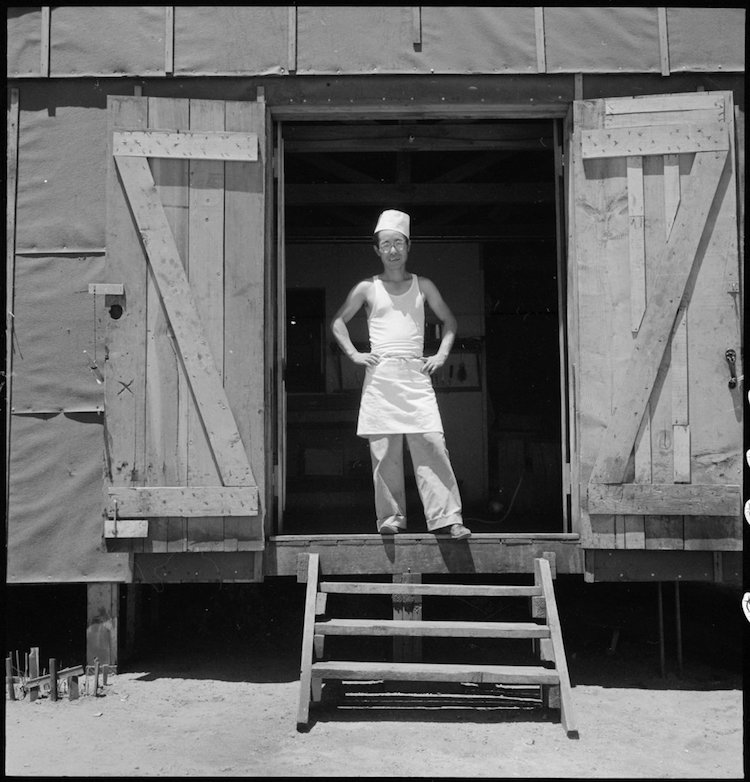

July 2, 1942—Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. A chef of Japanese ancestry at this War Relocation Authority center. Evacuees find opportunities to follow their callings.

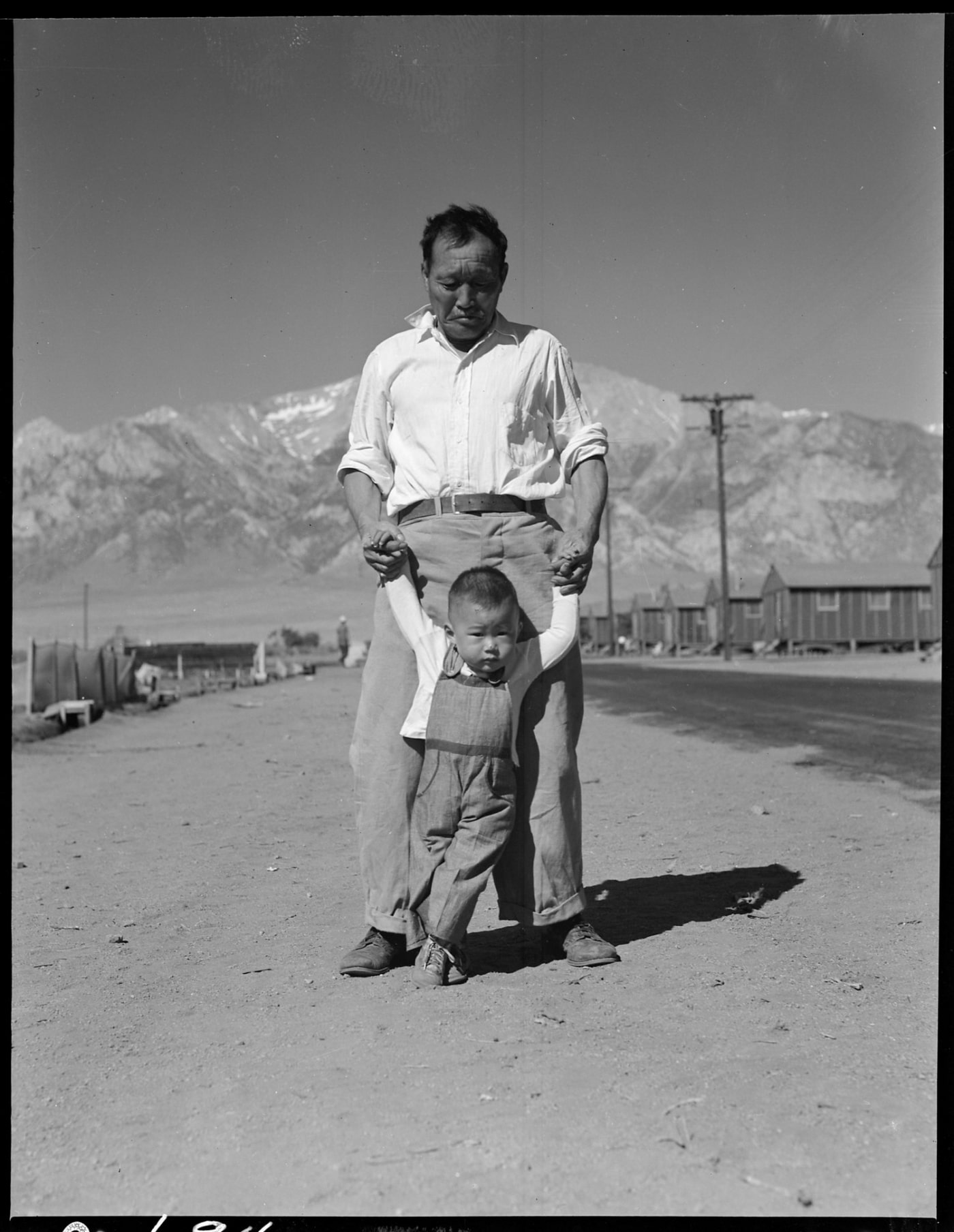

July 2, 1942—Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Grandfather of Japanese ancestry teaching his little grandson to walk at this War Relocation Authority center for evacuees.

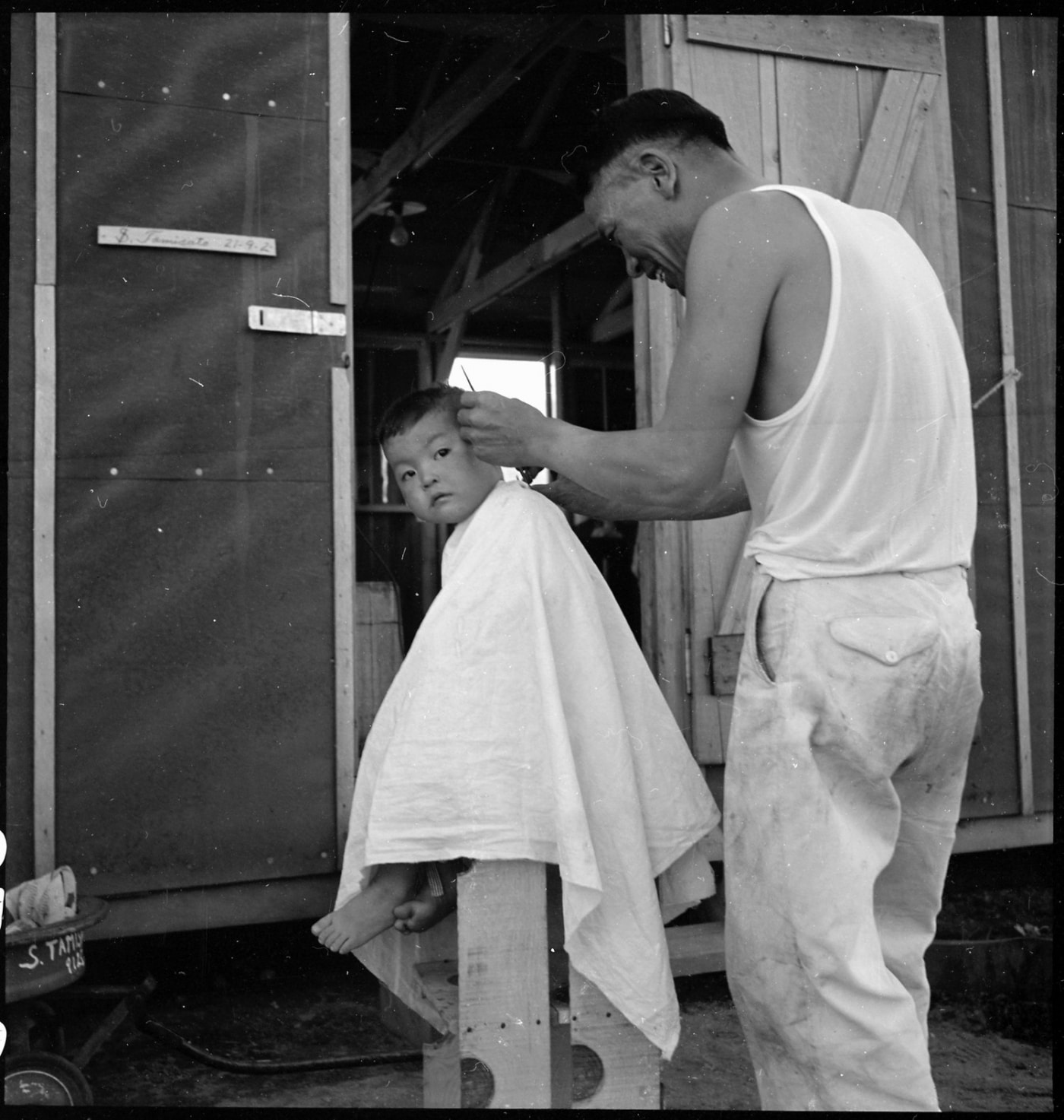

July 2, 1942—Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Little evacuee of Japanese ancestry gets a haircut.

June 30, 1942—Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. William Katsuki, former professional landscape gardener for large estates in Southern California, demonstrates his skill and ingenuity in creating from materials close at hand, a desert garden alongside his home in the barracks at this War Relocation Authority center.

June 30, 1942—Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. More land is being cleared of sage brush at the southern end of the project to enlarge this War Relocation Authority center for evacuees of Japanese ancestry.

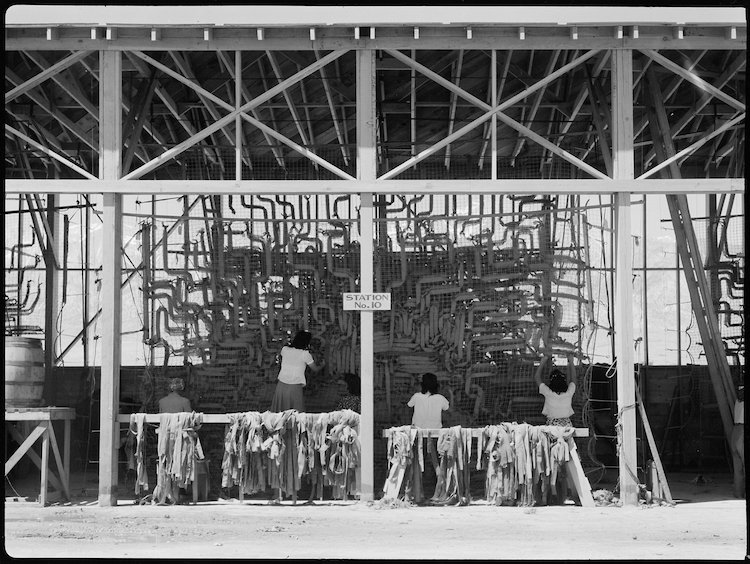

July 1, 1942—Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Making camouflage nets for the War Department. This is one of several War and Navy Department projects carried on by persons of Japanese ancestry in relocation centers.

June 28, 1942 — Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Guayule beds in the lath house at the Manzanar Relocation Center.

Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. Lawns and flowers have been planted by some of the evacuees at their barrack homes at this War Relocation Authority center.

h/t: [Neatorama]