Charles II in Armour, 1681, by Juan Carreño de Miranda. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

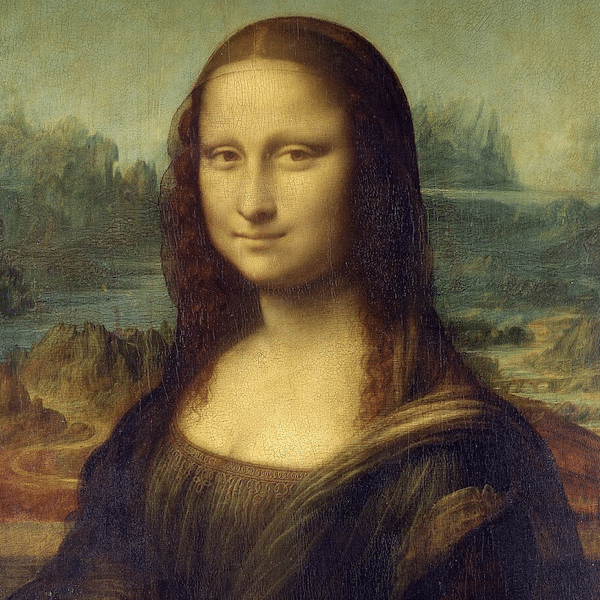

Thanks to modern technology, we’re able to uncover hidden images within historic works of art. One recent discovery comes from a 17th-century portrait of a royal. The Habsburgs ruled early modern Europe. For almost seven centuries, members of the clan intermarried and ruled across Europe. From Hungary to Portugal and Germany, their power rose and fell. Austria remained the center of the family's power, where they ruled from 1282 until 1918, for much of this period as Holy Roman Emperors. Another outpost was the Spanish monarchy, where that branch of the family aggressively consolidated power by marrying their own relatives. The result was Charles II—the last Habsburg king of Spain—whose life was depicted in the work of painter Juan Carreño de Miranda.

Carreño de Miranda was a court painter in Madrid whose portraiture was influenced by the Baroque greats such as Titian, Rubens, and Van Dyck. He spent the second-half of the 17th century churning out depictions of Spanish nobles and royalty, including Charles II. Charles II was born in 1661. His father, Philip IV, was the uncle of his mother Mariana of Austria. He became king as a child in 1665, so his mother acted as regent. However, Charles II was unfortunately destined for a life of difficulty and disease throughout his childhood and adulthood.

Charles II was the only one of his parent's children to survive to adulthood. His progress from boy to man has been revealed by x-ray in Carreño de Miranda's work Charles II in Armour. Painted in 1681 when the king was 20 years old, it depicts the monarch in military regalia with all the symbolism of a bold leader. His armor was made for his esteemed ancestor Phillip II, and the young king stands in front of a battle scene in the background. However, x-ray examinations of the painting reveal the canvas previously boasted a different image. Behind the young man was a much shorter, yet similar in appearance, child king. His hair in both images is loose, his face long, and his pose similar.

According to the Museo del Prado where the painting resides, “Carreño probably used what had become an obsolete portrait of the child king to paint on top of it a new portrait that updated his image as an adult, showing his taller stature. He then added a strip of canvas to the top in order to augment the height of the painting, and he trimmed the sides slightly so that it would correspond to the format of the painting of Philip IV (also painted by the artist).” The now hidden image of the younger king is closely related to a verson painted of the 10-year-old monarch which now hangs in the Museo de Bellas Artes de Asturias. But behind both images of the king lurk sad realities of inbreeding in one of Europe's most dominant royal houses.

Charles II was the result of 16 generations of Habsburg inbreeding, including his own parent's very close genetic relationship. Within these generations of the Spanish royal family, researcher Gonzalo Alvarez discovered, “[o]f 34 children, half died before their tenth birthday, and 10 died before their first.” Charles II was rare in surviving, but he was born with intellectual and physical disabilities which affected his health and hindered his ability to speak. In particular, he had the Habsburg jaw, a severe underbite which made life difficult. He was infertile and left no heirs, dying at 35, plagued by senility and seizures. This sad life lurks behind his royal portraits, which nonetheless attempt to frame the monarch as the last of a powerful dynasty.

Behind this portrait of the Spanish King Charles II is a past portrait, x-rays reveal. The king is depicted as younger and shorter in the older version.

Este retrato de Carlos II adulto que pinta Carreño de Miranda en 1681 esconde otra obra: Carreño reutilizó un lienzo en el que había pintado años antes un retrato del rey más joven y en la misma estancia, el Salón de los Espejos del Real Alcázar de Madrid pic.twitter.com/b5g29SJlq6

— Museo del Prado (@museodelprado) July 8, 2020

Charles II was a member of the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs, a ruling family of Europe known for inbreeding.

Carlos II de España, circa 1680, by Juan Carreño de Miranda. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

h/t: [Museo del Prado]

This article has been edited and updated from an earlier version that misspelled the Habsburgs.

Related Articles:

Restored Rembrandt Is on Sale for $30 Million

Lost Tudor Wall Paintings Found in Cambridge University Building

Family Discovers Their Living Room Painting Is a Lost Masterpiece Worth Millions