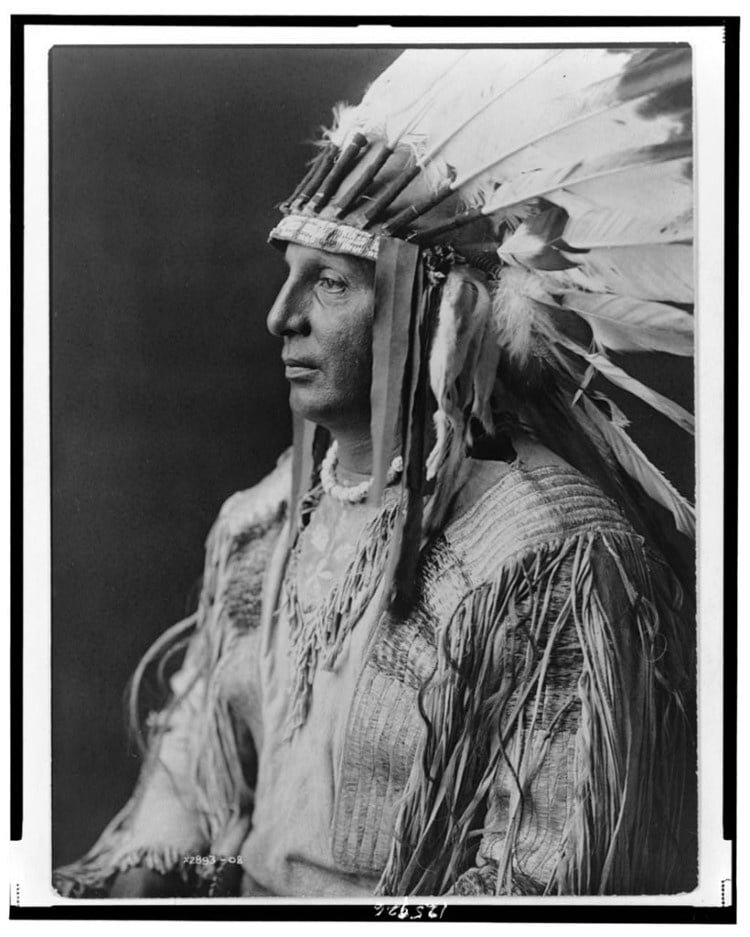

White Shield – Arikara, 1908 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis via Library of Congress, Public domain)

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

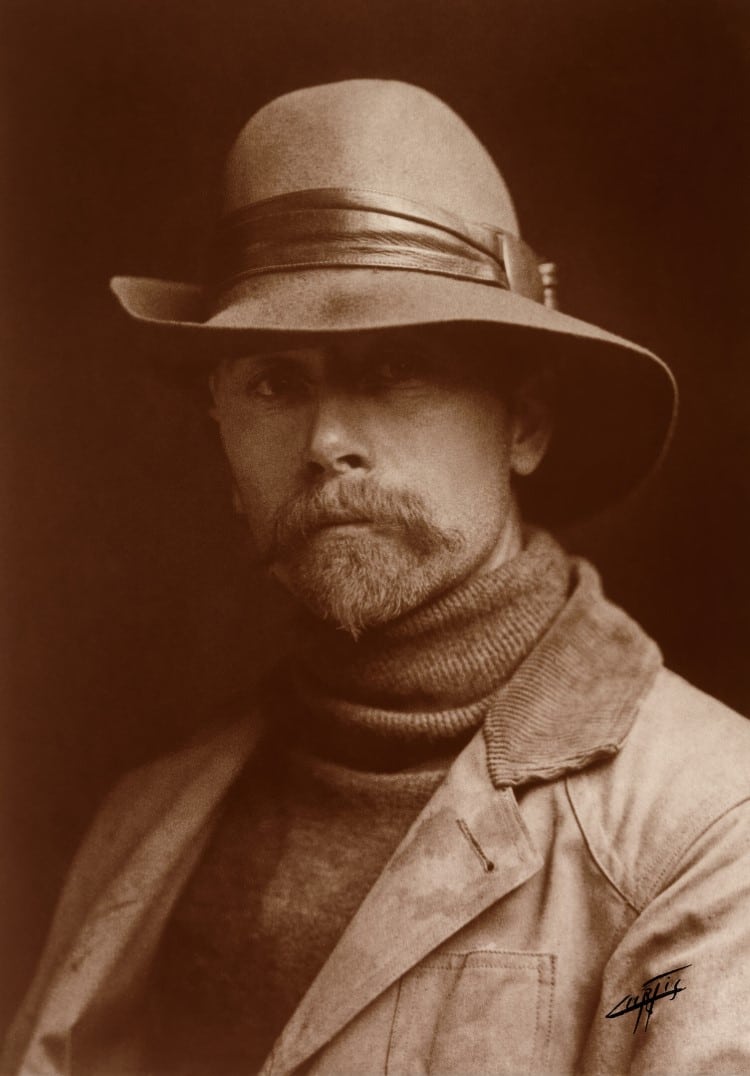

In what he perceived as a race against time, due to the American expansion and the intervention of the federal government, photographer and ethnologist Edward S. Curtis spent more than 30 years documenting Native Americans and their traditions.

Curtis referred to Native Americans as a “vanishing race,” and as such, wanted to document the customs and traditions of a wide variety of Native American tribes. To do so, he would need to secure wealthy patrons, allowing him to travel to different Indian territories, including a wide exploration of the American West.

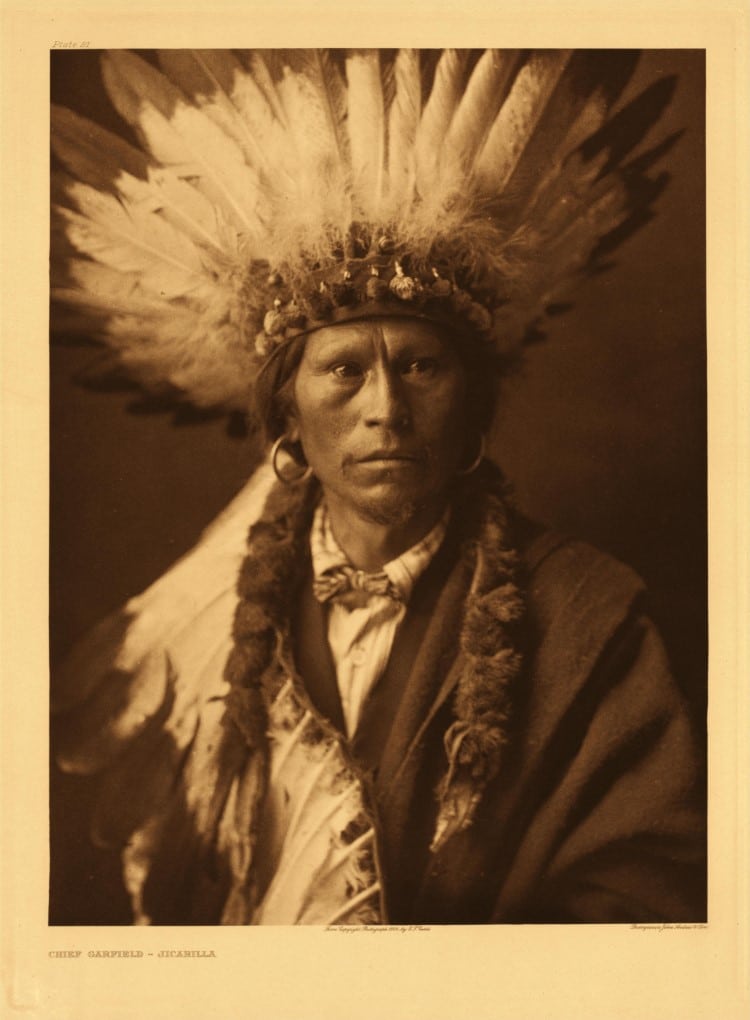

In 1906, with the sponsorship of J.P. Morgan, Curtis undertook the production of what was set to be a series of 20 volumes with 1,500 photographs of Native Americans. Initially, five years was designated for the project, but its ambitious scale pushed Curtis well beyond the deadline. Under the original terms of the sponsorship, Morgan paid out $75,000 over five years in exchange for 25 volumes and 500 original prints. This was enough for Curtis to purchase his initial equipment to make the arduous voyages to each tribe, but money quickly grew scarce.

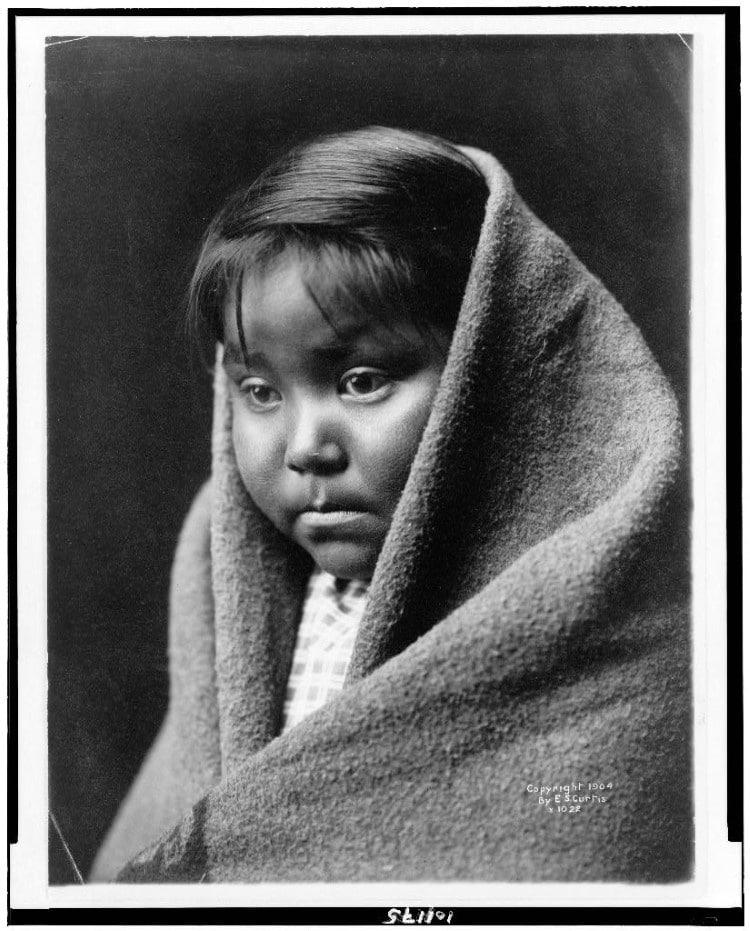

Curtis was on the move for more than three decades, living among dozens of tribes. During this time, he photographed well-known Native Americans, such as Geronimo, Red Cloud, Medicine Crow, and Chief Joseph. Interested in more than just photography, Curtis wished to capture a full view of Native American culture. While visiting more than 80 tribes, he created 10,000 wax cylinder recordings of Native American language and music, certainly an important component for preserving the tribes' legacy.

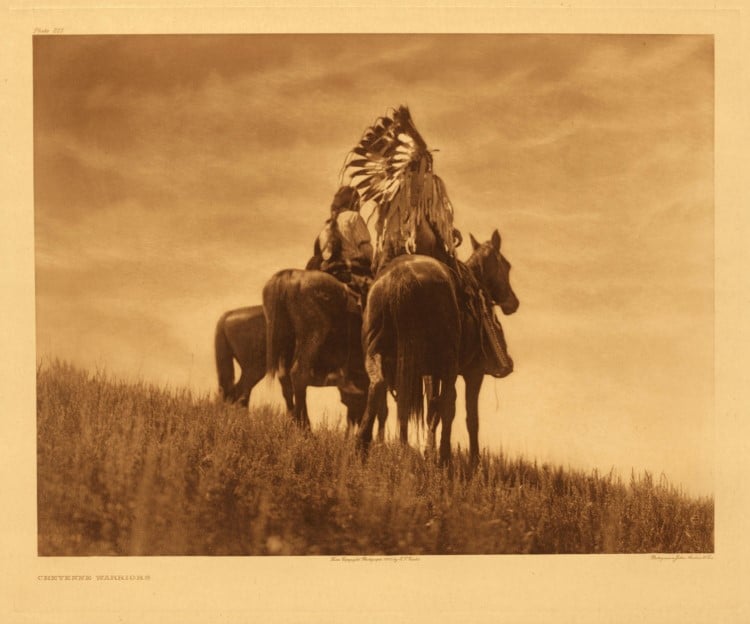

Cheyenne Warriors, 1905 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis via Northwestern University, Public domain)

To Curtis' dismay, The North American Indian was not the success he had envisioned—partially due to the onset of WWI, as well as diminishing interest in Native American culture. Less than half of the projected 500 sets were printed and scholars were skeptical of Curtis' observation skills. His images were posed, and he often paid people to perform in staged scenes or dances. While Curtis' imagery is a romanticized view of these indigenous populations, it is still valuable.

While there remains controversy over Curtis' choice to strategically eliminate traces of contemporary life from his later photographs, Laurie Lawlor, author of Shadow Catcher: The Life and Work of Edward S. Curtis, sees it differently. “When judged by the standards of his time, Curtis was far ahead of his contemporaries in sensitivity, tolerance, and openness to Native American cultures and ways of thinking. He sought to observe and understand by going directly into the field.”

Ultimately, he took over 40,000 images of the tribes he visited and documented a wealth of information about tribal culture. This includes folklore, clothing, traditional foods, housing, leisure activities, and ceremonies such as funerals.

It's estimated that today, production of the volumes would cost more than $35 million dollars. Incredibly, we can still view his work today. This is all the more amazing when one considers that Curtis destroyed all of his glass plate negatives. Curtis carried out this brutal act with his daughter after his ex-wife was granted ownership of his photo studio in their divorce.

There are many ways to still see Curtis's work. In 2004, Northwestern University digitized The North American Indian and placed it online. The Library of Congress also has a collection of more than 2,400 silver-gelatin photographic prints, about one-third of which are Curtis's Native American portraits.

If you are someone who loves to have a physical copy in their hands, Taschen published The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolio in 2015.

Born in 1868, photographer Edward S. Curtis spent over 30 years documenting Native American culture.

Self-portrait, 1899. (Photo: Edward S. Curtis via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

He visited over 80 tribes and took over 40,000 images to create his 20-volume opus, The North American Indian.

Navajo child, 1904 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis via Library of Congress, Public domain)

Óla – Noatak, 1928 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis via Library of Congress, Public domain)

Chief Garfield – Jicarilla, 1904 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis via Northwestern University, Public domain)

While his photographs are often staged and show his romanticized view of Native Americans, they are still historically valuable.

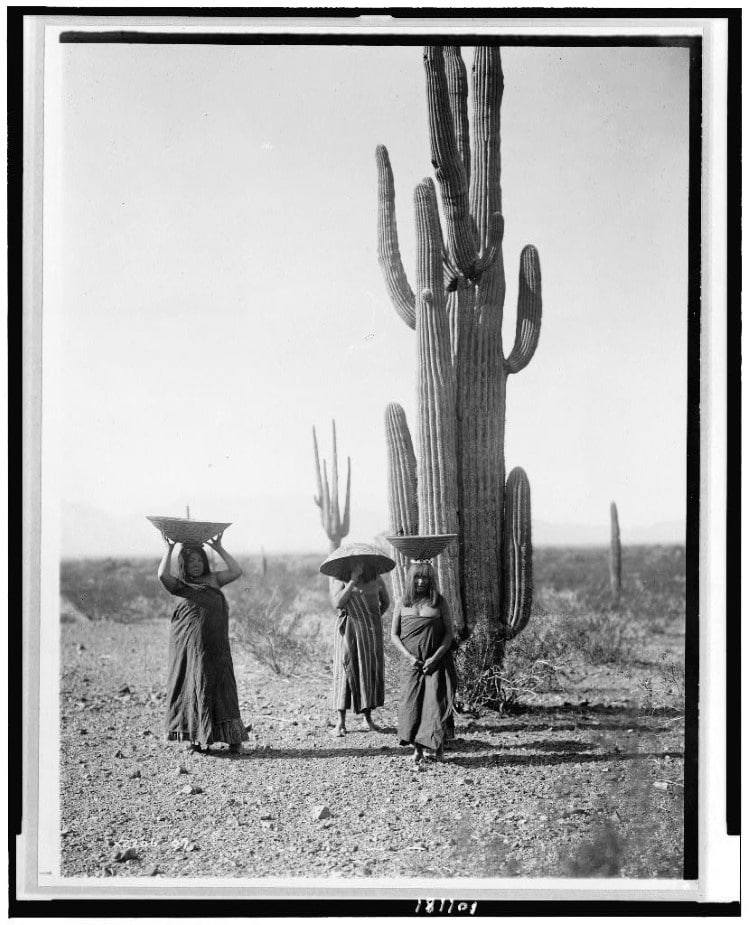

Maricopa women gathering fruit from Saguaro cacti, 1907 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis via Library of Congress, Public domain)

Apache man, 1903 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis via Library of Congress, Public domain)

His work ranges from portraits to photos of daily life, housing, and ceremonies.

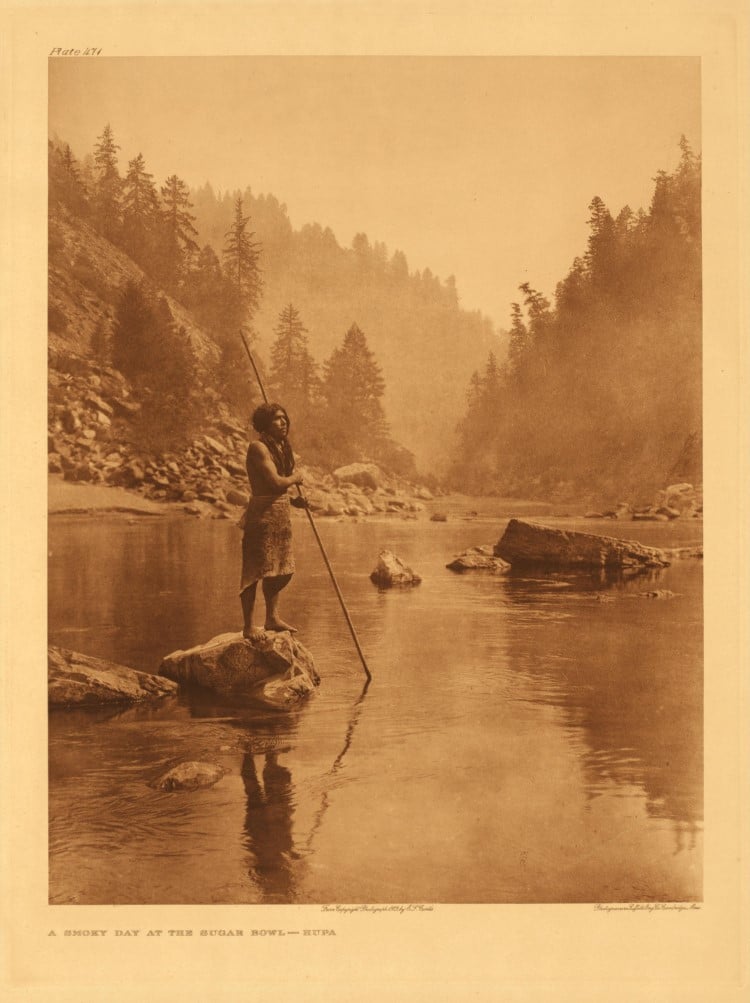

A Smoky Day at the Sugar Bowl – Hupa, 1923 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis via Northwestern University, Public domain)

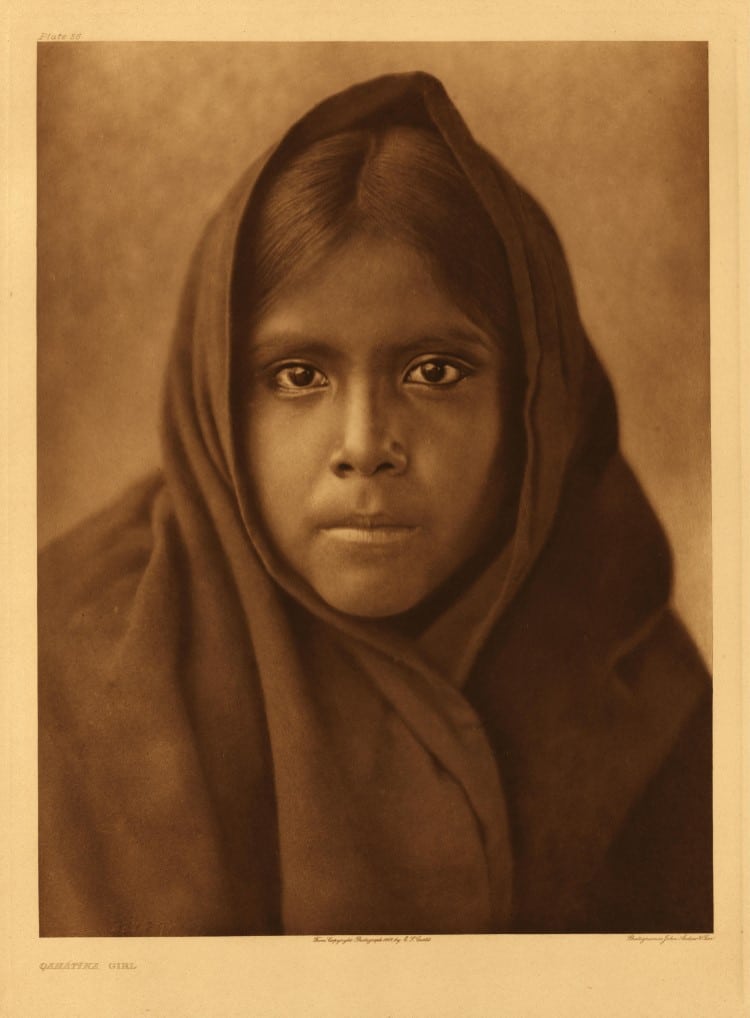

Qahátīka Girl, 1907 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis via Northwestern University, Public domain)

Blackfoot Finery, 1926 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis via Northwestern University, Public domain)

Today, his work has been digitized by Northwestern University and the Library of Congress.

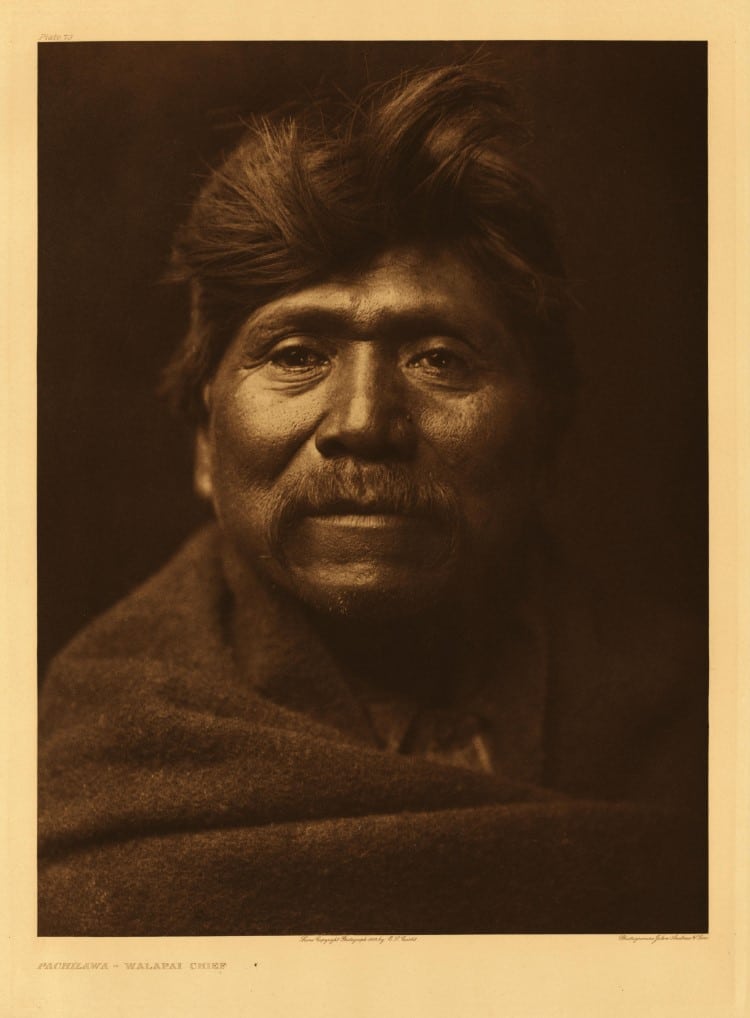

Pakílawa – Walapai Chief, 1907 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis via Northwestern University, Public domain)

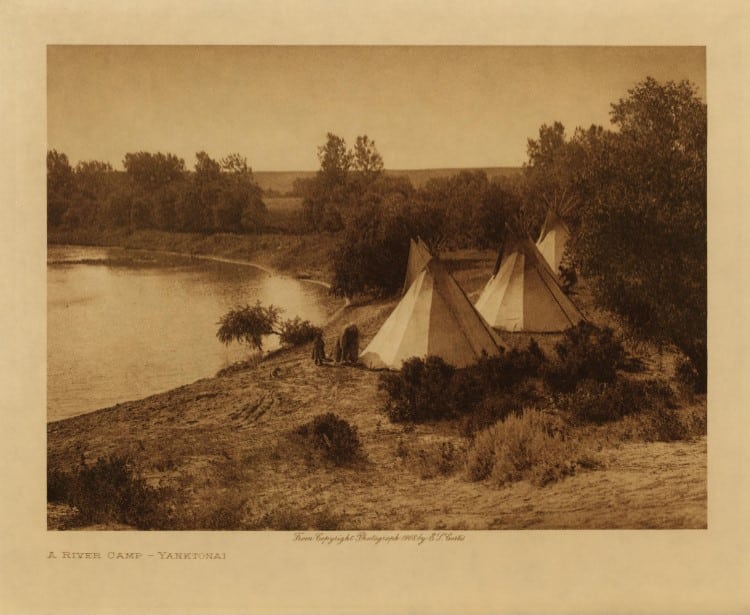

Yanktonai River Camp, 1908 (Photo: Edward S. Curtis via Northwestern University, Public domain)

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

Rare Images Depicting American Life in the 19th Century

Mathew Brady, the Story of the Man Who Photographed the Civil War

Tintype Photography: The Vintage Photo Technique That’s Making a Comeback

Smithsonian Acquires Rare Collection of Photos Taken by 19th-Century Black Photographers