Horizons. 1994. The Farm. Kaukapakapa. New Zealand. (Photo: David Hartley)

Noted New Zealand sculptor Neil Dawson has been a force in contemporary sculpture for over 30 years. Most well-known for his large-scale public sculptures, Dawson often plays with illusion in his whimsical pieces. By focusing on the use of lines and positive and negative space, his sculptures have made an indelible mark internationally.

Whether suspending light and airy globes above public squares or using a single line to create a dramatic silhouette, Dawson's site-specific works are closely tied to their surrounding environment. “His sculptures flout convention in their lightness of feel, their transparency and their escape from the conventions of earthbound pedestal-based display,” writes Dr. Michael Dunn, Professor Emeritus at the University of Auckland, in his book New Zealand Sculpture: A History.

Though Dawson has focused less on public sculpture lately, his presence is clearly felt in the work he's left behind across New Zealand. From the inverted cone of The Chalice in Christchurch to the iconic Horizons at the Gibbs Farm sculpture park in Auckland, there is no denying the impact of his work. Horizons, in particular, is a tour de force where perception, illusion, and simplicity intermingle to great effect. Perched as a piece of paper on a hill, the work takes on new life throughout the day as the environment fills the enormous blank page.

We had a chance to speak with Dawson about his illustrious career and his contribution to the field of sculpture. Read on for My Modern Met’s exclusive interview.

Chalice. 2001. Christchurch. New Zealand. (Photo: Vicki Piper)

What first attracted you to sculpture as a medium?

I failed sculpture in my first year at art school. During my repeat year, I got hooked on making things and discovered the freedom that sculpture offered. At the time, you could paint something in the sculpture department but couldn't build something in painting. The late 1960s was a time of experimentation in all the arts and during the 4 years I studied sculpture, I developed a life long passion for sculpture, architecture, and engaging with the public through site-specific installations.

Echo. 1982. Christchurch. New Zealand.

The use of positive and negative space plays an important role in your work. What drew you into this spatial work and the use of illusions?

I have always been interested in how drawing can work in three dimensions. Wanting to create work outside galleries demanded working on a large scale. Using line to create illusions became a way I could create a substantial experience in a space. The work was then animated by the movement of the spectator and the constantly changing weather and light conditions.

Kahu. 1994. Kaikoura. New Zealand. (Photo: Anne Noble)

People often underestimate the demands of creating public sculpture once the finished piece is up. How did you first get involved in creating public artwork?

My first involvement in public art was through creating temporary installations inside and outside galleries and in public spaces. These were site-specific installations developed through building a relationship with the client and the site. The aim was to create a unique experience that worked in concert with the historical, physical, and visual character of the site.

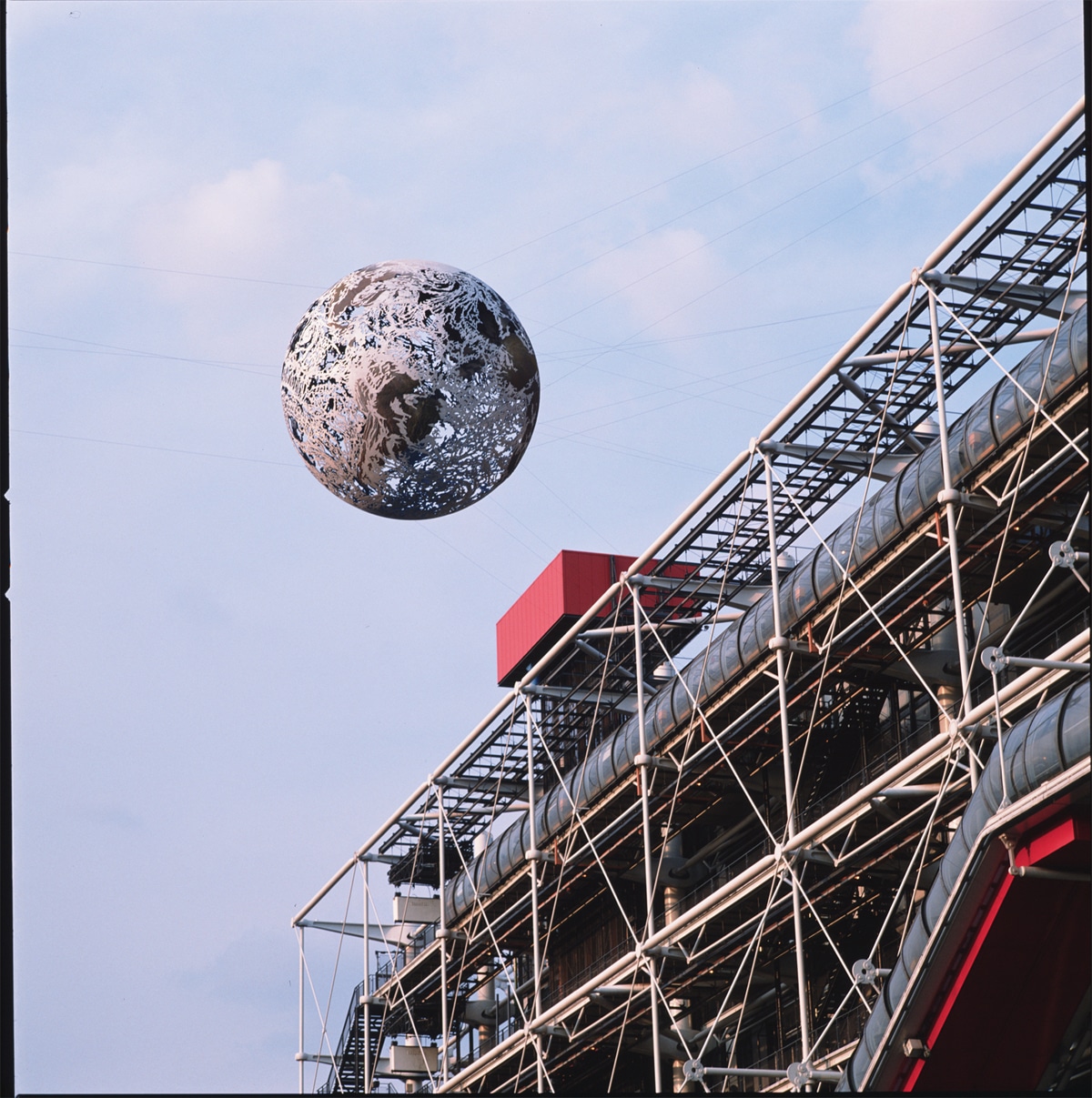

These were included in the Sydney Biennale (Vanity) and Magiciens de la Terre at the Centre Pompidou. (Globe). I have since created numerous permanent public works throughout New Zealand, Australia, Asia, and the UK.

Globe. 1989. Paris. France. (Photo: Bill Nichol)

Any particularly memorable experiences when installing one of these pieces?

I see every project as an adventure as they tend to be filled with challenges and surprises. Each has its stories. Installing Globe in 1989 was a “pantomime” carried out over the heads of the jugglers and sword swallowers in Beaubourg Square. The 4.5 meter diameter foam and carbon fiber globe was pulled up 20 meters into the air by hand using ropes and block and tackle. The work was suspended on 3mm-thick stainless steel wires attached to the Pompidou Centre and the chimney walls 80 meters away on the other side of the square. I recall negotiating with embassies and police departments to get approvals through, purchasing cables in the gallery car park, and scrambling around on crumbling chimney walls. It was hung with the assistance of a team of workers I brought from New Zealand.

Fanfare. 2004. Sydney. Australia.

You've stepped away from these public pieces in recent years. Can you explain the decision behind that?

I am always interested in responding to invitations to work in exciting spaces—public or private—and have continued to do large-scale commissions in the last 20 years. However, larger public works have recently become less of a focus, because I have found the competition opportunities don't always provide the relationships and collaboration that my projects require. I have also found that design and implementation processes have become considerably more complex, costly, and risk-averse.

Kahu. 2019. Christchurch. New Zealand.

How does the creation of smaller sculptures differ from the public work and in what ways is it similar?

The smaller works are like the playroom for ideas. Concepts and structures can be explored on an intimate scale without the pressures that an outdoor or public space brings. I have always enjoyed building things with my hands. They seem to think more clearly than I do.

All of the large works begin with a series of small-scale models as this is the best way to get to know it. It is important that the client has a very clear idea of what is coming.

Ripples. 1987. Hamilton. New Zealand.

How does it feel to represent the New Zealand art scene on an international level?

I have always seen myself and my work in relation to the world, the sphere being an ongoing theme in my work for 30 years.

There are heaps of New Zealand artists in the international scene: Michael Parakowhai, Simon Denny, Dane Mitchell, Luke Willis Thompson, Francis Uprichard, Bill Culbert, Fiona Pardington, Boyd Webb.

Horizons 1994. The Farm. Kaukapakapa. New Zealand. (Photo: David Hartley)

What is next for you?

Living in a coastal property, I am savoring native birds and bush and working on cloud and feather sculptures.

“In the same way it takes numerous glimpses of a public artwork to build up a relationship, it takes just as long to let the environment seep into you before creating something from that experience.”

Ferns. 1998. Wellington. New Zealand.