In Lucknow, India, a small family-run workshop is helping preserve a prehistoric artistic tradition. Jalaluddeen Akhtar learned bone carving from his uncle in 1980 and has been producing stunning creations ever since. Now, his son Aqeel works alongside him in one of the very few workshops that are able to keep its doors open. Aqeel, who learned the art of bone carving when he was 14, is using the internet to bring their work to a wider audience in the hopes of helping them continue with the tradition.

Bone carving has a special place in Indian culture. During the Mughal dynasty, royals would commission elaborate bone carvings to adorn their palaces. Of course, those historic carvings were done in ivory, but once that was made illegal, artisans like Akhtar simply pivoted and began using buffalo bones. In fact, that is what Akhtar continues to use today, sourcing his materials from butchers who are happy to get rid of these bones.

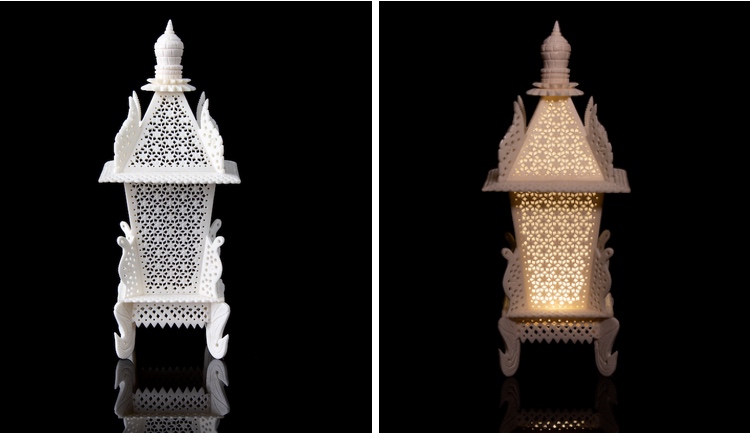

Once in his hands, these bones are broken down, cleaned, and carved into stunning works of art. From lamps to pens to knives to earrings and necklaces, there is nothing that can't be made. And whatever bone fragments don't make it into the final carving are sold to businesses that grind them down and place them in fertilizers. In this way, nothing goes to waste.

While government support has helped sustain the craft, the high cost of electricity, scarcity of materials, and the shrinking local market have put the tradition at risk. Currently, the Akhtar family teaches government-subsidized workshops in the community, passing their knowledge along. And, together with a handful of specialist artisans, they continue to create stunning bone carvings.

With a diminishing appetite for their work locally in India, most of their carvings are shipped abroad to international customers. Aqeel hopes to capitalize on this interest by making their catalog available online and posting finished pieces on Reddit, Instagram, and Facebook.

We had the chance to speak with Aqeel about this incredible artform and what he hopes that people take away from their art. Read on for My Modern Met's exclusive interview.

Can you share a bit of history about bone carving and its place in Nawabian culture?

Since humans started to hunt, they utilized the bones of animals to make tools. As shaping bone was much easier than when compared to stone, along with the hardness of bones being higher than wood, it was used to make tools that were intended to last a long time. Eventually, jewelry was also made to be worn by people as a symbolic gesture of power and as a piece of remembrance.

Later, around the 17th century, as people started to refine their skills of carving, bone (such as ivory and Rhino horns) was increasingly used as a medium to display their carving skills. Being prevalent in the Indo-Gangetic region, the Nawabs started to notice the immense skill displayed by the artists of the time. Artworks such as jewelry, intricately carved walking sticks, and jewelry storage chests were commissioned by the local rulers and kings. This significantly catapulted the art of bone carving and to the extent where the poaching of elephants for ivory became commonplace in the region.

Later in the 20th century, many left this field of art after the government rightly banned the trade of ivory in order to bring the poaching of elephants to a complete stop. While some took their skills to wood carving, others took up completely different areas of work to survive. Today, we are one among the few remaining (less than 10 families) descendants of the artists with Nawabi lineage. Although we are on the edge financially, we are committed to continuing and passing on our culture in hope of better days and increased recognition.

Why is it important for you to keep this tradition alive?

While we greatly appreciate the progress and development that the modern world has given us, we believe some aspects are better if preserved. We believe it is both our responsibility and our honor to keep alive the culture that our forefathers began. Although mostly ivory was prevalent in this artform before the government banned it, causing most to move to other works, we were one among the only few to change our medium to buffalo bones instead of abandoning our culture.

The art of bone carving is a practice that precedes almost all the popular art forms. When such is the case, it is an absolute honor for us to keep the artwork alive. It is our opinion that there is an immense opportunity to create works of art that reflect modern culture. Creating works of an ancient art form that represents modern thinking is something few people do today.

How long do the more intricate carvings take?

The most intricate work that we are currently working on is restoring a lamp that was made about 60 years ago. The lamp measures about five feet tall and has carvings whose accuracy measures less than a millimeter all over its body. The base of the lamp was damaged by unknown causes. Restoring that it has already taken years and yet it remains unfinished. Our masterpiece lamps take over 1,000 hours of work by skilled craftsmen who have been in practice for at least 15 years.

Is everything carved by hand, or are lasers also used?

The process of bone carving does involve machines, but they’re limited to only crude ones, such as a sawmill to cut the bones into smaller pieces and a drill press to initiate the Jaali work. These were also incorporated only recently just so the trivial aspects of the work don’t take too much time.

We also use a small buffing machine to smoothen the artwork in the end. A mini handheld Dremel tool is used to make carvings, but that's limited to the crude shaping of the work—the detailing is made by hand using needle files. The Jaali work—the net, star, or flower-shaped latticework—is initiated by drilling holes and then the central part of the carving is entirely done by hand using needle files. No stencils are used anywhere in the process. And no, no lasers are used in the process.

What do you hope that people take away when they look at your work?

Many people, when they look at our artwork, are reserved in their opinion as there is a taboo of using ivory in the past. Our thinking, like others', has transformed, and we understand that harming animals just for the sake of art is heinous. We would greatly appreciate it if people observed our determination to change our views while holding on to our culture through our artwork.

When people look at our work, we desire that they see not only the superficial intricacies of the artwork but also its history, which has managed to transcend through thousands of years. We would like them to recognize through our art how far we’ve come from who we once were.

Learn more about how Jalaluddin Akhtar and his son Akheel are keeping the ancient tradition of bone carving alive.

Art Renatus: Website | Instagram | Facebook

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Art Renatus.

Related Articles:

The Fading Art of Traditional Chinese Dongyang Wood Carving

Intricate “Candle Carving” Forms Blooming Designs with Layered Wax

16th Century Gothic Boxwood Miniatures With Extremely Detailed Carvings

Artisans Hand-Carve Incredible 3D Wood Art To Keep Traditional Wood Carving Techniques Alive