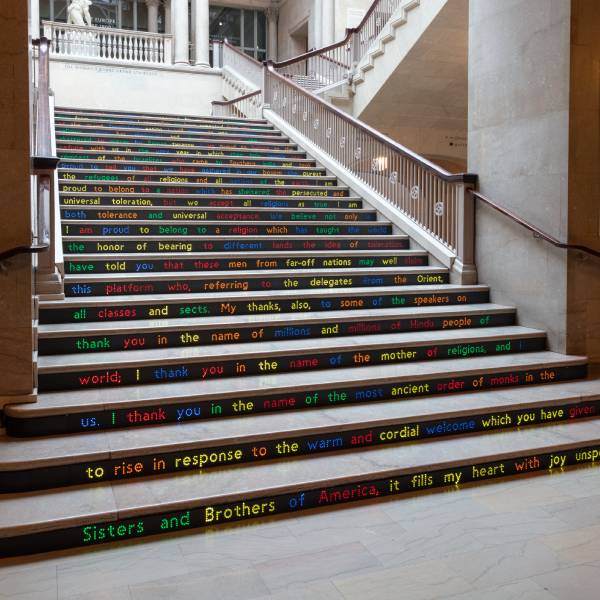

“Super/Natural,” 2025, stained glass panels and steel and wooden frame. (Photo: Claire Oliver Gallery)

When Judith Schaechter first encountered stained glass during her studies at RISD, she instantly knew that the material would dramatically alter the trajectory of her career. It turns out that her intuition was correct.

For years, the Philadelphia-based artist has produced intricate glass compositions, complete with vibrant color palettes and enchanting patterns. What defines her practice above all, though, is her preoccupation with the human condition and the tensions between what she describes as the “wretched and the beautiful.” These interests manifest as atmospheric, intense, and at times unsettling works, in which humans are contorted with grimaces; whales are bloody and beached on the shore; and axe-wielding figures swing at each other through shattered shards of glass. In these works, there’s both whimsy and destruction, beauty and strangeness, encouraging viewers to contemplate beyond what they initially see.

Aside from these themes, Schaechter also gravitates toward organic imagery. Across her practice, flowers, insects, birds, and vast landscapes coalesce, echoing stained glass traditions and their preference for the sublime, sacred, and supernatural. These feelings are exactly what the artist hopes to conjure in her latest project, aptly titled Super/Natural.

The installation, which she created during a residency at the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics, resembles a chapel with a three-tiered cosmos. Each of the work’s 65 glass panels practically vibrates with color and life, reflecting Schaechter’s ongoing fascination with biophilia and the natural world. Those who enter the sanctuary are inundated with a riot of imagined plants, bugs, and animals, all rendered in delicately stained glass.

“The images, all derived from the imagination, are intended to call to mind a sense of nature as understood by a human mind—they are not ‘real’ plants or birds,” Schaechter tells My Modern Met. “It is my belief the human mind can conjure awe independent of external experience and hopefully Super/Natural will prove to be an example of that.”

On March 20, 2026, an exhibition of the same name will land at Claire Oliver Gallery in New York, allowing visitors to explore that sense of awe for themselves. Super/Natural will not just encompass its eponymous installation, but three new lightbox works, including Reynardine, which incorporates an experimental process of layered glass.

“Stained glass is inherently awe-some, its deployment in houses of worship is no coincidence,” the artist adds. “The radiance of the colored light is both warming and inspiring in a very physical way.”

Ahead of the exhibition’s opening, we spoke with Judith Schaechter about her artistic practice and how she created her new Super/Natural installation. Read on for our exclusive interview with the stained glass artist.

“Super/Natural,” 2025, stained glass panels and steel and wooden frame. (Photo: Claire Oliver Gallery)

“Super/Natural,” 2025, stained glass panels and steel and wooden frame. (Photo: Claire Oliver Gallery)

“Super/Natural,” 2025, stained glass panels and steel and wooden frame. (Photo: Claire Oliver Gallery)

What originally drew you to stained glass as an artistic medium?

As a painting student at RISD, I wandered into the stained glass class one day. I was instantaneously attracted. At first contact with the material and process, I knew that was what I wanted to pursue for the rest of my life.

Who knows how I could have come to that recognition back then, but I remember that I liked the fact that stained glass has only a brief, and much neglected, history. I was quite intimidated by the history of painting. I can see now that I had some kind of yearning to be a technical innovator, and it seemed like, in painting, pretty much everything has been tried and then done to death repeatedly.

Furthermore, Modernism seemed to value things like heroic brushstrokes and was weighty with profoundly serious intellectual theory, which I liked but felt no personal connection to. Glass operated in the margins and I intuited I could get away with more there!

“Wondermoths,” 2025, stained glass in lightbox

What compels you about the materiality of glass?

There are many reasons for my attraction to the material of glass itself. First, transmitted light is inherently attractive. I was also interested in the technical aspect. Ironically, I found my “artistic voice” was liberated by technical restriction. I felt “in sync” with glass. The labor intensiveness, the variety of processes involved, and the repetitious movements allowed me to focus and concentrate.

By the time I managed to do something to the glass, I had developed feelings of attachment and was hardly going to throw it away. Glass was the only thing I could bear to work with long enough to become fluent in.

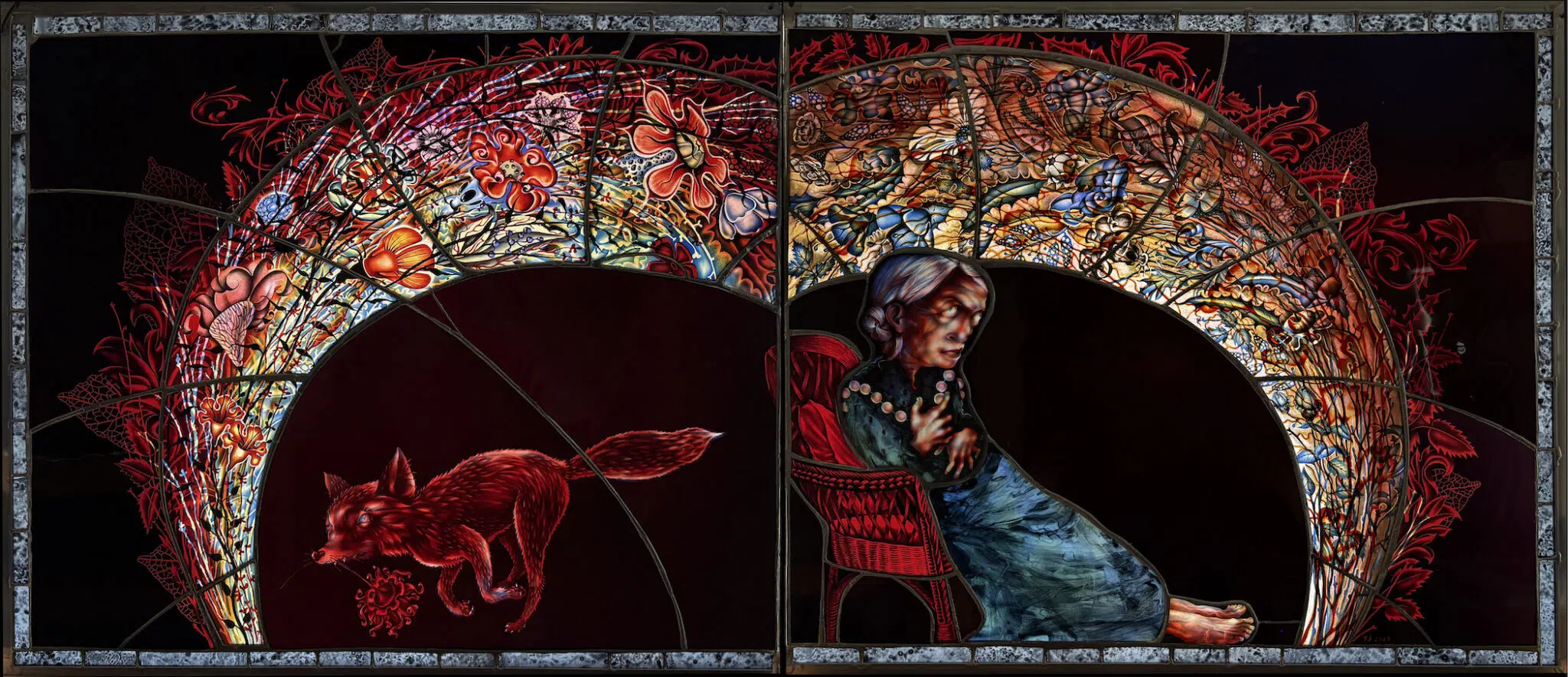

“Reynardine,” 2026, stained glass panels and steel and wooden frame. (Photo: Claire Oliver Gallery)

How did you develop your own personal style within stained glass?

I have never intentionally tried to develop a style. In fact, I was taught to try not to as it was a form of branding and would constrict my development as an artist. But looking at my work, it has a voice and a feel to it that I hope is uniquely mine. This evolved organically and comes from years of making and drawing. My own hand surprises me—why do my images look like my own? I can’t say.

When it comes to influence, it’s very broad, and probably more from culture than from nature. I look at images constantly almost from the point of view of an alien. What makes an image legible, intriguing, resonant? How can one balance objective and subject “reality” in a picture?

“Super/Natural,” 2025, stained glass panels and steel and wooden frame. (Photo: Claire Oliver Gallery)

“Super/Natural,” 2025, stained glass panels and steel and wooden frame. (Photo: Claire Oliver Gallery)

“Super/Natural,” 2025, stained glass panels and steel and wooden frame. (Photo: Claire Oliver Gallery)

Super/Natural contends with biophilia and other organic themes. What compels you about these subjects, and how do you represent or visualize them throughout your work?

The piece Super/Natural resulted from my residency at the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics (PCfN). Biophilic design is studied at PCfN to better understand how nature-based design affects cognition and improves well-being. Biophilic principles are often used in hospitals and office buildings to create “refresh rooms” and non-secular chapels—places to lower stress and encourage feelings of serenity and peace. Additionally, there is research showing us the necessity of the experience of “AWE” to our well-being. So, Super/Natural was created in the hopes of evoking a sense of awe in addition to peace and serenity.

Stained glass is inherently awe-some, its deployment in houses of worship is no coincidence. The radiance of the colored light is both warming and inspiring in a very physical way. The images, all derived from the imagination, are intended to call to mind a sense of nature as understood by a human mind—they are not “real” plants or birds. It is my belief the human mind can conjure awe independent of external experience and hopefully Super/Natural will prove to be an example of that.

In addition to being inspired by the work of PCfN, I was interested in creating a “personal temple” for a single viewer, in the centuries old tradition of stained glass in ecclesiastical spaces. It is my hope to create a venue for contemplation of inner space, meaning, how we experience spaces neurologically and psychologically; as well as outer space, or, how we extend ourselves into our surroundings. For me, this would include an environmental message. The earth is our home, and it can be a welcoming home and perhaps if we thought of it as such, we might be less inclined to sit by while we destroy it.

On a more personal level, I am a life-long city person who does not own a car, so I do not often have the chance to experience natural spaces beyond city parks. Super/Natural is a result of that perspective.

“Super/Natural,” 2025, stained glass panels and steel and wooden frame. (Photo: Claire Oliver Gallery)

How did you develop the ideas behind Super/Natural?

I am committed to not imposing my will on the creative process and am deeply suspicious of “having an idea.” Inspiration, for me, is never “an image in my head that wants to get out.” When I think I have had an idea of this sort, it always has the elusive quality of a dream half remembered. I pick up a pencil, and it almost instantaneously vanishes entirely into the ether. But drawing is the beginning of what will end up looking like I had an “idea.” All of my work derives from a sort of “automatic drawing” or doodling process. With Super/Natural, I drew at lab meetings once a week for two years. This generated a lot of material!

The next stage is to play with those doodles in Photoshop, cross-pollinating themes and compositions. I find that free play leads to concepts I could never have imagined, and I find that very exciting.

Finally, I have to get to the point where I have enough information—and it can be very little and very vague—where I can generate a cutting pattern for the glass. Then, I begin a technical process—but before I get into that, I want people to know that the creativity doesn’t end there. Working with the glass itself is very spontaneous and there is much improvisation going on. So, while, I may have a pattern, I have been known to change course multiple times along the way!

“Super/Natural,” 2025, stained glass panels and steel and wooden frame. (Photo: Claire Oliver Gallery)

What was the technical process behind producing Super/Natural?

I use a material called “flash glass.” Flash glass is a type of handblown glass with a paper-thin veneer of intense color on a base layer of lighter color.

After cutting and shaping the glass to a cartoon (a cutting pattern), I sandblast the surface. This is a process by which one can “frost” the colored layer, sometimes removing it altogether to reveal the clear layer below. After sandblasting, I engrave smaller details using a flexible shaft engraver. I also use diamond files to make smooth tonal variations in the color. The easiest way to understand this is that it’s kind of similar to cameo carving (although less three-dimensional).

One reason there is a lot of color in each section of my pictures is that the flash glass is layered—sometimes up to three pieces deep. The only paint I use is a type of glass enamel which fires onto the surface of the glass permanently. Sometimes I also use silverstain (which is yellow) and is the origin of the term “stained glass.”

“Super/Natural,” 2025, stained glass panels and steel and wooden frame. (Photo: Claire Oliver Gallery)

“Super/Natural,” 2025, stained glass panels and steel and wooden frame. (Photo: Claire Oliver Gallery)

What do you hope people will take away from Super/Natural?

I don’t tend to see my work in omniscient terms. I don’t always have a message—anything you get from the work is fine, they are open to interpretation. I am really just trying to make empathetic and inspiring images.

With more figurative work, I have been asked many times why the work is “depressing,” a label I really hope is not accurate. I have always found comfort in art, especially in art that transforms the wretched into the beautiful—say, unspeakable grief, unbearable sentimentality, or nerve wracking ambivalence—and represents these feelings in such a way that it’s inviting and safe to contemplate and captivating to look at. I am at one with those who believe art is a way of feeling one’s feelings in a deeper, more poignant way and I hope my work contributes to that particular dialogue.