View this post on Instagram

A keen observer of everyday life, Norman Rockwell is known for his idealized images of American history. He had a 47-year-long association with The Saturday Evening Post, for which he provided over 320 cover images. Many of his paintings are now iconic and illustrate important societal themes including patriotism, gender equality, and racial integration.

Rendered in his signature realist style, Rockwell’s paintings were executed with an immense amount of detail. He often used humor in his work and executed his scenes with tremendous respect for his subjects. The legendary illustrator wanted to create work that made viewers “want to sigh and smile at the same time.”

Rockwell's work was often criticized by abstract expressionists at the time; they believed his paintings shouldn’t be taken seriously. But even today, his work stands out in the memory of many.

Here are six Normal Rockwell paintings that define his prolific career.

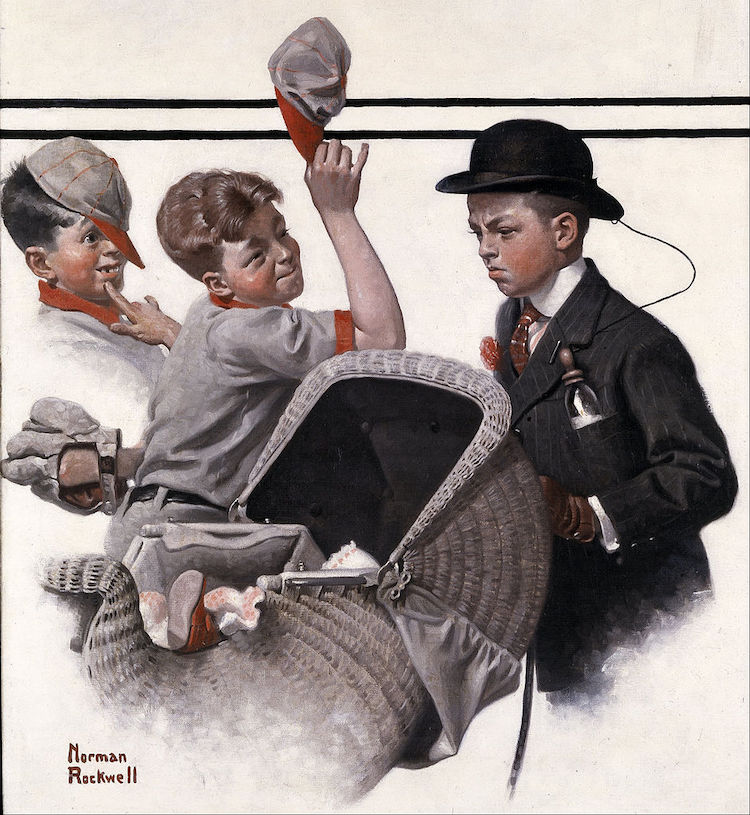

Boy With Baby Carriage, 1916

“Boy With Baby Carriage” by Norman Rockwell, 1916. Photo: Wikimedia Commons (Public domain)

Boy With Baby Carriage was Rockwell's first cover for The Saturday Evening Post. This humorous depiction of boyhood features three figures and a wicker carriage with a baby inside it. One of the boys pushes the carriage with an earnest expression, while the others appear to playfully mock him. The painting explores the theme of coming-of-age and captures the trials and tribulations of the human experience.

Rockwell was particularly talented at provoking empathy for his characters. The Post's art editor Kenneth Stuart commented that “no guide is needed for Norman's work” since the “warmth of his understanding reaches [the] People [who] experience his paintings.” Stephanie Plunkett, the Chief Curator at the Norman Rockwell Museum, backed that view when she said his images represent “who we are, what we could be, what we could look like [and] what our values could be.”

A Red Cross Man in the Making, 1918

“A Red Cross Man in the Making” by Norman Rockwell, 1918. Photo: Wikimedia Commons (Public domain)

Rockwell painted A Red Cross Man in the Making for The Red Cross Red Crescent magazine, a publication for the Red Cross organization. The humanitarian group is dedicated to protecting human life and health, and here, the goodwill of a Red Cross kid is illustrated. A scout is depicted attending to the injury of a small dog, while a larger dog looks concerned. Rockwell put a huge amount of effort into the details of the painting, including the scout’s textured uniform and hat as well as the tools he uses. The painting was chosen to be used as Rockwell's first calendar cover for the Boy Scouts of America.

Freedom From Want, 1942

“Freedom From Want” by Norman Rockwell, 1942. Photo: Wikimedia Commons (Public domain)

Considered one of Rockwell’s most famous works, Freedom From Want is the third in a series of four titled Four Freedoms. The collection was inspired by President Franklin Roosevelt's January 1941 “Four Freedoms State of the Union Address” to Congress. In it, he outlined four essential human rights that should be protected—freedom from want, freedom from fear, freedom of speech, and freedom of worship. This painting, as well as the three others based on the other “freedoms,” were published in The Post in 1943. The paintings were so successful that they were also produced as posters for schools, post offices, and other public buildings.

Freedom From Want (also known as I'll Be Home for Christmas) depicts a large, happy family who is about to enjoy a sumptuous home-cooked meal. Each of the characters is based on a real person whom Rockwell photographed separately before painting them together in the scene. The iconic work represents an idealized view of the post-war “American Dream.”

Rosie the Riveter, 1943

View this post on Instagram

During World War II, women began taking up male working roles in factories and shipyards. The strong Rosie the Riveter character represented many of these invaluable women who were recruited to helped to build war supplies. Rockwell's painting was used as the cover illustration for The Post on Memorial Day, May 29, 1943. With a powerful woman as the subject, the artwork was intended to encourage more women to give up their domestic roles and seek work. The popular image is still used today as a symbol for feminism and female empowerment.

“Rosie” is based on real-life Vermont resident, Mary Doyle O'Keefe. She posed for Rockwell with a ham sandwich and a plastic toy machine gun, while her confident pose was borrowed from Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling painting of the prophet Isaia. “I was very pleased […] I am proud of this painting,” said O’Keefe years later. “It's a symbol of what women did for the war, to do their part, and to give up their nail polish.”

The Discovery, 1956

View this post on Instagram

The Discover was the last of Rockwell’s popular holiday-themed covers for The Post. (Although he continued to contribute illustrations for seven years after.) It humorously depicts a young boy who has just found his father’s hidden Santa costume, revealing the myth of Father Christmas. Rendered with textured details, this piece marked a subtle shift towards greater realism—in fact, it almost looks like a photograph. The expression of shock on the child’s face is so vivid, you can almost feel his disillusionment, too.

Rockwell’s wide-eyed model, Scott Ingram, became a minor celebrity at the time. He received fan mail, and was asked to autograph pictures and books, and even appeared on the TV show Hallmark Hall of Fame with Rockwell.

The Problem We All Live With, 1964

View this post on Instagram

The Problem We All Live With is an iconic image of the Civil Rights Movement. It depicts Ruby Nell Bridges, a six-year-old African American girl who went to the William Franz Elementary School in Louisiana. It was one of two all-white public schools that implemented desegregation in 1960. During the dramatic shift, the school experienced riots and death threats against Black children. For her safety, Ruby had to be escorted to school each day by four United States Marshals.

Published in 1964, the poignant painting was Rockwell’s first for LOOK magazine. Then later in 2011, President Barack Obama displayed the painting at the White House as part of the 50th anniversary of Bridges's historic walk.

Related Articles:

Illustrator Uses Art to Give a Voice to the Black Lives Matter Movement [Interview]