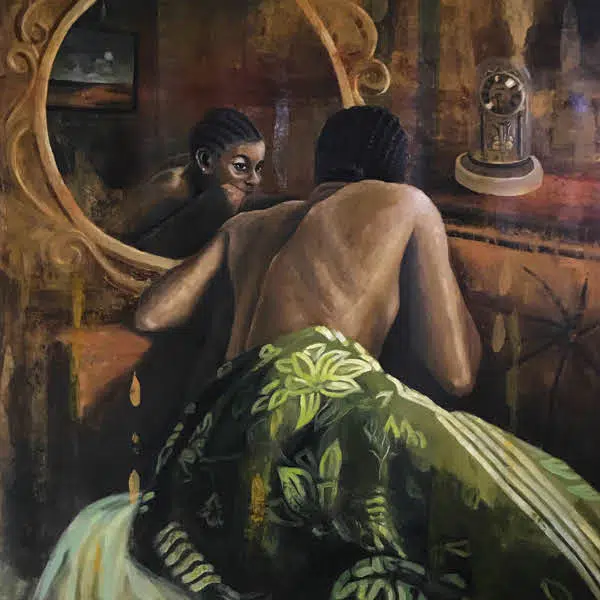

“Gentle,” Piezography Ink (2015).

Photographer Oliver Klink focuses his work on the complex ways in which modern life unfolds. His award-winning, black-and-white imagery has been featured in National Geographic and Popular Photography, among other publications. In particular, his Consequences series combines his artistic abilities with anthropological investigation.

Consequences, which sees Klink traveling to remote, yet accessible, areas, seeks to address threats to cultural diversity through modernization. In an age where globalization is expanding, how can unique traditions continue to thrive? Through visits to countries such as Myanmar, Bhutan, and China, Klink seeks these answers.

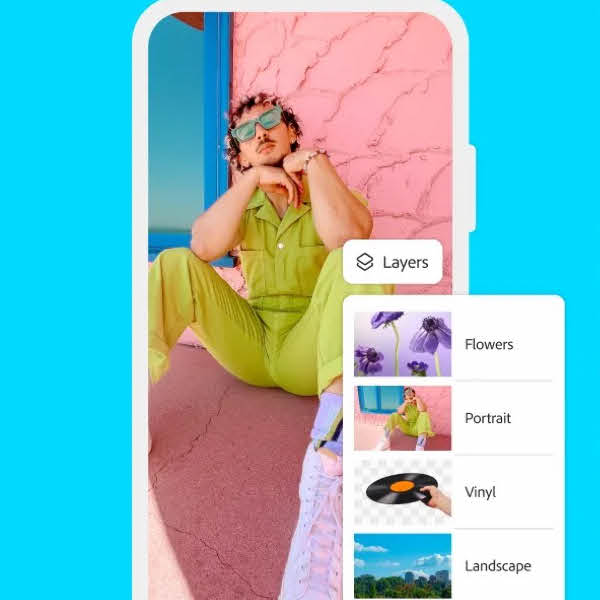

Klink's work has a timeless feel, owed in large part of his mastery of Piezography. This digital printing process, where photographers mix their own inks, enhances the highlights and shadow of each photograph. In this way, Klink is able to pluck each moment from the background, artistically shaping the final result.

We were lucky enough to speak with Klink about his work in general and how Consequences has developed. Read on for the full interview.

“God's Rays,” Piezography Ink (2014).

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and how you found your way into photography?

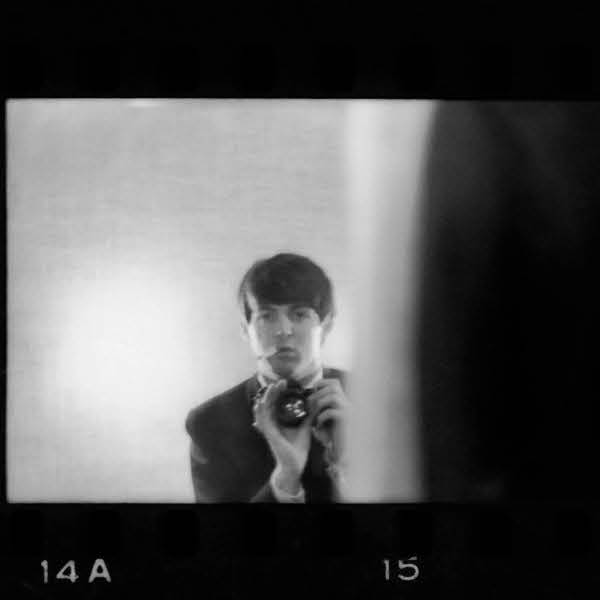

My name is Oliver Klink. I was born and raised in Switzerland. My combined studies in physics and photography were the catalyst to understanding light and how to record it in an artistic fashion. The fascination for printing came from my dad, who was a printmaker.

I vividly recall the smell of the ink, the paper flying thru Heidelberg presses, and flipping thru books he printed. I started as a large format analog photographer and was in awe of the quality of the images and the prints. I moved to digital in 2001, trying to find the best camera and printing methodology available to match my analog work. In the last three years, I have perfected my printing skills by mixing my own ink—a process called Piezography—and mastering large-scale printing.

“Stepwell,” Piezography Ink (2016).

Your work has an anthropological approach. What led you in this direction?

As a fine art photographer, I travel the world to capture the complex modern world constantly unfolding in new and unexpected ways. I capture our cultural changes, the environments we inhabit, and the insights into our world and ourselves. My artistic goal is to tell stories with my images, making the viewers dream, and providing a glimpse of “the world as it should be.”

“Ancient Farming,” Piezography Ink (2015).

How did Consequences come about?

I am an avid reader of books and “photographs.” I have marveled at the work of Art Wolfe, Chris Rainer, Jimmy Nelson, Amy Vitale, and others who have focused on documenting remote cultures. During my travels, I have found that as human beings we are intrigued by customs, what we feel is disappearing. Unfortunately, when we meet these people, they are presented to us as an “attraction,” which tends to make them lose their true identity.

I wanted to travel to “accessible places” and give a voice to the people that are going through changes, sometimes against their will, sometimes for the better, but most of the time at a pace that is beyond comprehension.

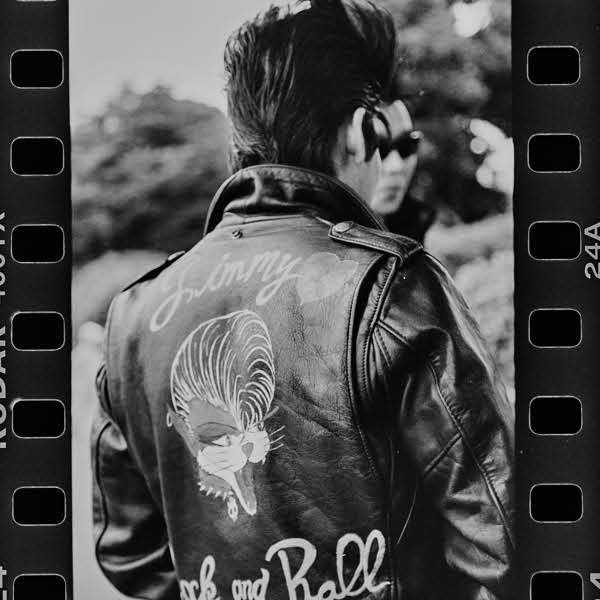

“Tattoed 1961,” Piezography Ink (2014).

“Herding instinct,” Piezography Ink (2014).

Is there a particular experience that stands out among the ones you had shooting the series?

Each experience is precious in itself. The two elderly touching hands in Gentle was mesmerizing, as Chinese culture tends to be emotionless in public. The portrait of Tattooed 1961 came about after she heard that I was photographing in the neighboring village. She walked over 5 km (3 miles) to see what was happening. When she arrived, she was exhausted and leaned on her walking stick.

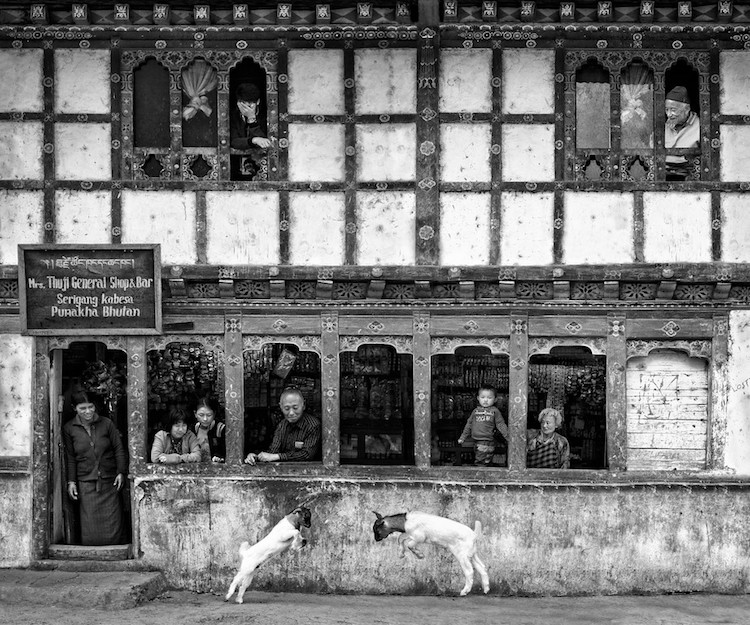

God’s rays became even more meaningful after the 2016 earthquake destroyed countless old temples in Bagan, Myanmar. Herding Instinct depicts the philosophy of Bhutanese people, where the government prides itself to gauge its success in GNH (Gross National Happiness).

The biggest challenge is to find the remote places that still “exist” and maintain their traditions. Local festivals, typically not published on the Internet and hard to pin down on “exact” dates, are gems to attend.

“Spring Festival,” Piezography Ink (2016).

How do locals react to your presence?

Unfortunately, I do not speak all the local national languages. The challenge is not just to find a guide, but to find the guide who speaks the local “dialect.” After a few days roaming around the small villages, I become known for my “smile” and “bobbing head.” Locals become curious about my “whereabouts”, and they start to strike a conversation through my guide. Sharing images and stories is an attention grabber and generate interest in them participating in my project.

Typically a return trip is more productive, pending that the time frame between the trips is short. I do like to visit these people at different times of the year, where I am able to experience various customs based on their work habits, weather patterns, family outings, and downtime.

“Horse Ride,” Piezography Ink (2016).

What do you hope people come away with when viewing the images?

I have seen people watching these images off a computer monitor, off a slide projector at a show in Buenos Aires, off my 24”x 29” portfolio box, and off gallery walls printed and framed as large as 80” wide. The emotions people felt are very different. The more time an individual spends contemplating the intricacy of the image, the more they get involved with the subject. The subtleties of the image triggers trips down memory lane and/or what the future holds for us.

I am always intrigued by how visitors react to my images and would welcome comments.

Anything else you'd like to share?

I keep adding new images to this project, as I am traveling to new places. In January 2017 I visited my 100th country. As the project increases in size, the output will mutate to additional formats, such as books, continuous solo and group exhibits, and documentaries. Look for future news at www.oliverklinkphotography.com.

Oliver Klink's incredible travel photos capture remote cultures around the globe.

“Growing Up,” Piezography Ink (2016).

“Home,” Piezography Ink (2012).

“Tattoed 1963,” Piezography Ink (2014).

“Community Affair,” Piezography Ink (2014).

“Laborious,” Piezography Ink (2015).

Oliver Klink: Website | Facebook