This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

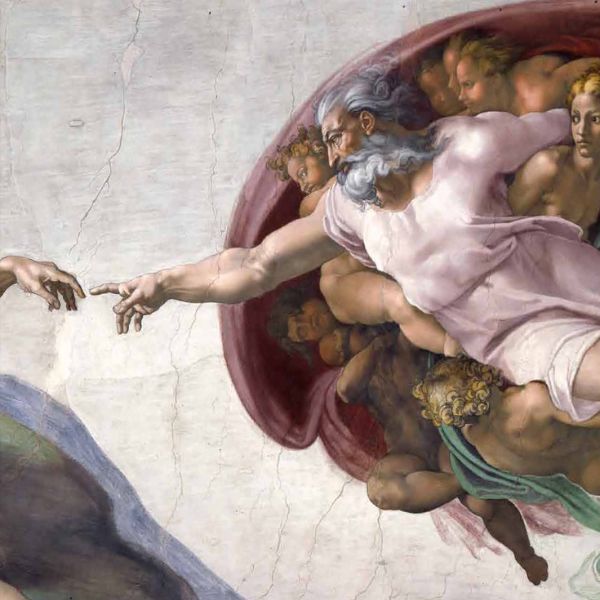

Long before Raphael the hotheaded, red-eye-mask-wearing Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle entertained children onscreen, there was Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (best known simply as Raphael) the esteemed painter who’d won over a cultured crowd of art connoisseurs. By his mid-20s, Raphael was already a star. At the top of his game, this master of the Italian Renaissance had been invited by the pope to live in Rome, where he would spend the rest of his days. Starting in 1509 he began decorating the first of four rooms in the Papal Palace. Collectively, these Raphael Rooms, along with Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel exemplify the High Renaissance fresco technique.

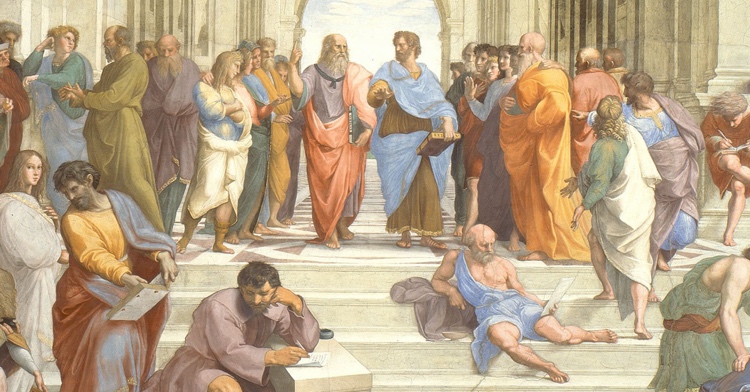

In particular, Raphael’s fresco The School of Athens has come to symbolize the marriage of art, philosophy, and science that was a hallmark of the Italian Renaissance. Painted between 1509 and 1511, it is located in the first of the four rooms designed by Raphael, the Stanza della Segnatura.

But just what does this famous painting mean? Let’s look at what the iconic The School of Athens meant for Raphael as an artist and how it’s become such a symbol of the Renaissance. At the time, a commission by the pope was the apex of any artist’s career. For Raphael, it was validation of an already burgeoning career.

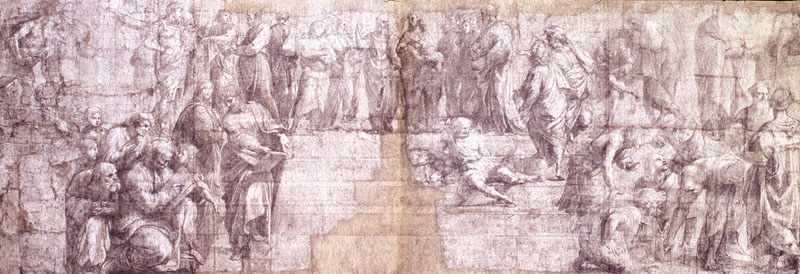

“The School of Athens” preparatory cartoon

Raphael was in Florence when he received word that Pope Julius II, the same man who asked Michelangelo to paint the Sistine Ceiling, asked him to decorate apartments on the second floor of the Vatican Palace. He was hoping to outshine the Early Renaissance paintings his predecessor, Pope Alexander VI, had done in the Borgia Apartments, which sat directly below. It could be seen as a bold choice, as a young Raphael had never executed fresco works as complex as the commission would require. At that point, he’d mainly been known for his small portraits and religious paintings on wood, in addition to a few altarpieces. Some believe that his friend Bramante, who was the architect of St. Peter’s, recommended him for the job. They’d both grown up in Urbino and knew each other well.

Raphael rose to the challenge, creating an extensive catalog of preparatory sketches for all his frescoes. These would later be blown up in full-scale cartoons to help transfer the design to the wet plaster. Working at the same time as Michelangelo, it’s thought that this helped push and inspire Raphael by stimulating his competitive nature.

Stanza della Segnatura and the Four Branches of Knowledge

Sala della Segnatura. (Photo: 0ro1 via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL)

The School of Athens is one of four wall frescoes in the Stanza della Segnatura. Each wall represents one of the four branches of knowledge during the Renaissance—theology, literature, justice, and philosophy. The room was set to be Julius’ library, and therefore Raphael’s overall concept balances the contents of what would have been in the pope’s study.

In the 15th century, a tradition of decorating private libraries with portraits of great thinkers was common. Raphael took the idea to a whole new level with massive compositions that reflected the four branches. Read as a whole, they immediately transmitted the intellect of the pope and would have sparked discussion between cultured minds that were lucky enough to enter into this private space.

The School of Athens was the third painting Raphael completed after Disputa (representing theology) and Parnassus (representing literature). It’s positioned facing Disputa and symbolizes philosophy, setting up a contrast between religious and lay beliefs.

Take a virtual tour of the Stanza della Segnatura via the Vatican Museums website.

The School of Athens

Set in an immense architectural illusion painted by Raphael, The School of Athens is a masterpiece that visually represents an intellectual concept. In one painting, Raphael used groupings of figures to lay out a complex lesson on the history of philosophy and the different beliefs that were developed by the great Greek philosophers.

Raphael certainly would have been privy to private showings of the Sistine Chapel in progress that were arranged by Bramante. Though Raphael’s work, in many ways, could be seen as more complex due to the number of figures placed in one scene, he certainly was influenced by the great artist’s work. This is particularly evident by the long figure thinking in the foreground, as we’ll soon see.

In fact, modern influence seeps in more frequently than one would think, particularly when it comes to the faces used for certain figures in The School of Athens. Let’s take a look, group by group, to pick apart the concept and see who appears in the famous fresco.

Who are the figures in The School of Athens?

Plato and Aristotle

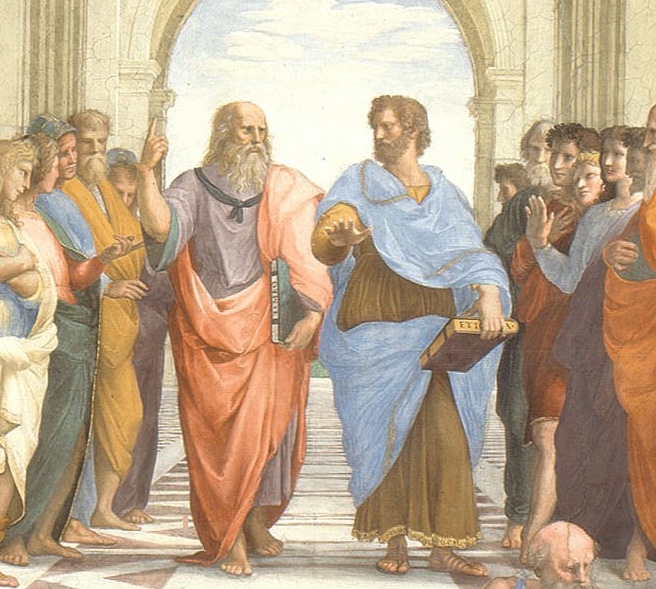

The two main figures in the work are placed directly under the archway and in the fresco’s vanishing point, a compositional trick to draw the viewer’s eye to the most important part of the painting. Here, we see two men who effectively represent the different schools of philosophy—Plato and Aristotle.

An elderly Plato stands at the left, pointing his finger to the sky. Beside him is his student Aristotle. In a display of superb foreshortening, Aristotle reaches his right arm directly out toward the viewer. Each man holds a copy of their books in their left hand—Timaeus for Plato and Nicomachean Ethics for Aristotle.

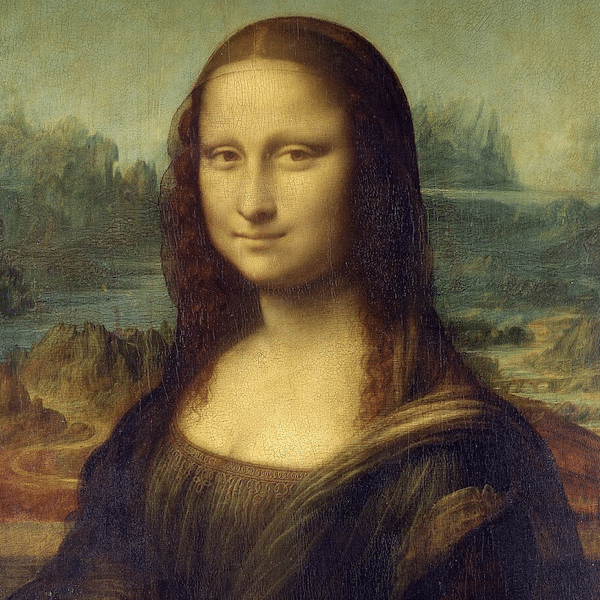

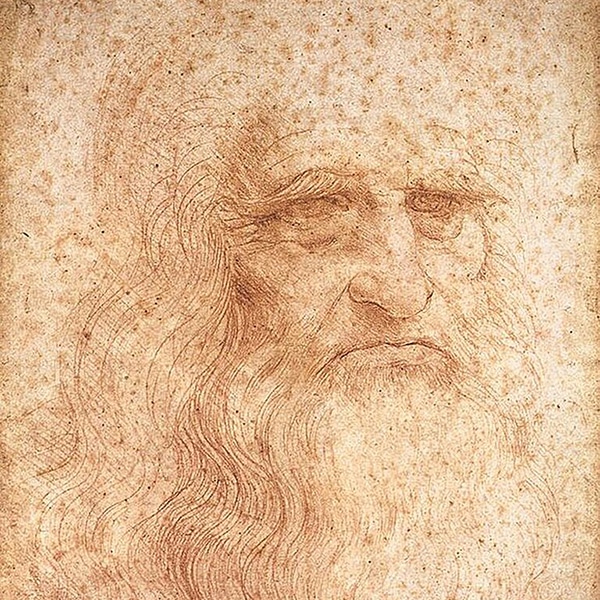

Plato’s gesture toward the sky is thought to indicate his Theory of Forms. This philosophy argues that the “real” world is not the physical one, but instead a spiritual realm of ideas filled with abstract concepts and ideas. The physical realm, for Plato, is merely the material, imperfect things we see and interact with on a daily basis. Interestingly, some people believe that Raphael used Leonardo da Vinci’s face for Plato, based on similarities from his self-portrait.

Conversely, Aristotle’s hand is a visual representation of his belief that knowledge comes from experience. Empiricism, as it is known, theorizes that humans must have concrete evidence to support their ideas and is very much grounded in the physical world.

Scholars argue that this divide in philosophies, placed at the center of The School of Athens, is the core theme of the painting.

So who is everyone else? It’s not always crystal clear, as Raphael doesn’t arm all his characters with attributes that give away their identity. Fortunately, there are quite a few that scholars can agree on.

Socrates

To the left of Plato, Socrates is recognizable thanks to his distinct features. It’s said that Raphael was able to use an ancient portrait bust of the philosopher as his guide. He’s also identified by his hand gesture, as pointed out by Giorgio Vasari in Lives of the Artists. “Even the Manner of Reasoning of Socrates is Express’d: he holds the Fore-finger of his left hand between that, and the Thumb of his Right, and seems as if he was saying You grant me This and This.”

Among the crowd surrounding Socrates are his students, including the general Alcibiades and Aeschines of Sphettus.

Pythagoras

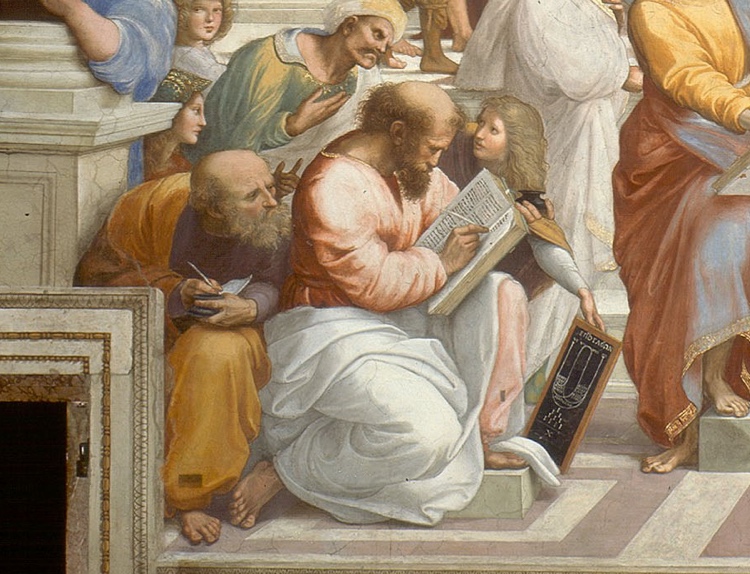

In the foreground, Pythagoras sits with a book and an inkwell, also surrounded by students. Though Pythagoras is well known for his mathematical and scientific discoveries, he also firmly believed in metempsychosis. This philosophy states that every soul is immortal, and upon death, moves to a new physical body. In this light, it makes sense that he would be placed on Plato’s side of the fresco.

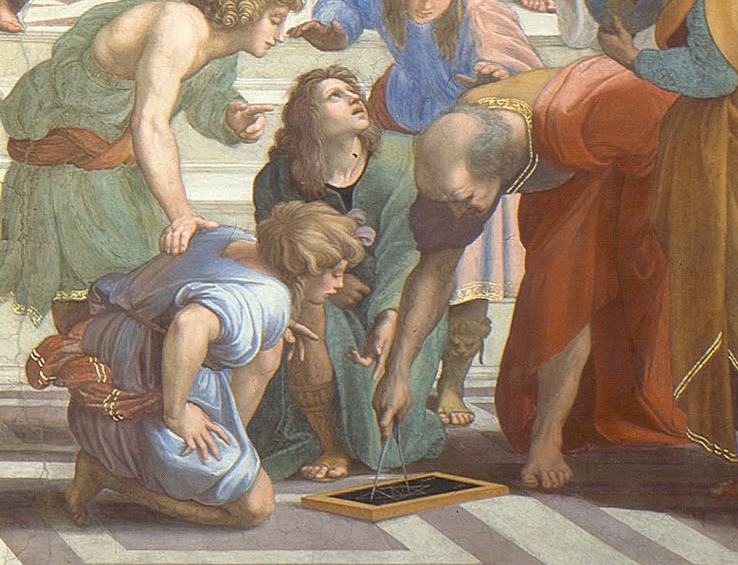

Euclid

Mirroring Pythagoras’ position on the other side, Euclid is bent over demonstrating something with a compass. His young students eagerly try to grasp the lessons he’s teaching them. The Greek mathematician is known as the father of geometry, and his love of concrete theorems with exact answers demonstrates why he represents Aristotle’s side of The School of Athens. Experts believe that Euclid is a portrait of Raphael’s friend Bramante.

Ptolemy

The great mathematician and astronomer Ptolemy is right next to Euclid, with his back to the viewer. Wearing a yellow robe, he holds a terrestrial globe in his hand. It’s thought that the bearded man standing in front of him holding a celestial globe is the astronomer Zoroaster. Interestingly, the young man standing next to Zoroaster, peaking out at the viewer, is none other than Raphael himself. Incorporating this type of self-portrait is not unheard of at the time, though it was a bold move for the artist to incorporate his likeness into a work of such intellectual complexity.

Diogenes

It’s universally agreed that the older gentleman sprawled on the steps is Diogenes. Founder of the Cynic philosophy, he was a controversial figure in his day, living a simple life and criticizing cultural conventions.

Heraclitus

One of the most striking figures in the composition is a brooding man seated in the foreground, hand on his head in a classic “thinker” position. This figure doesn’t show up in Raphael’s preliminary drawings and plaster analysis shows that it was added later. Art historians Roger Jones and Nicholas Penny write in their book Raphael that it “is probably Raphael’s first attempt to appropriate some of the heavyweight power of Michelangelo’s Sistine Prophets and sibyls.”

Long thought to be a portrait of Michelangelo himself, the brooding nature would have matched the artist's character. In the realm of philosophers, he is Heraclitus, a self-taught pioneer of wisdom. He was a melancholy character and did not enjoy the company of others, making him one of the few isolated characters in the fresco.

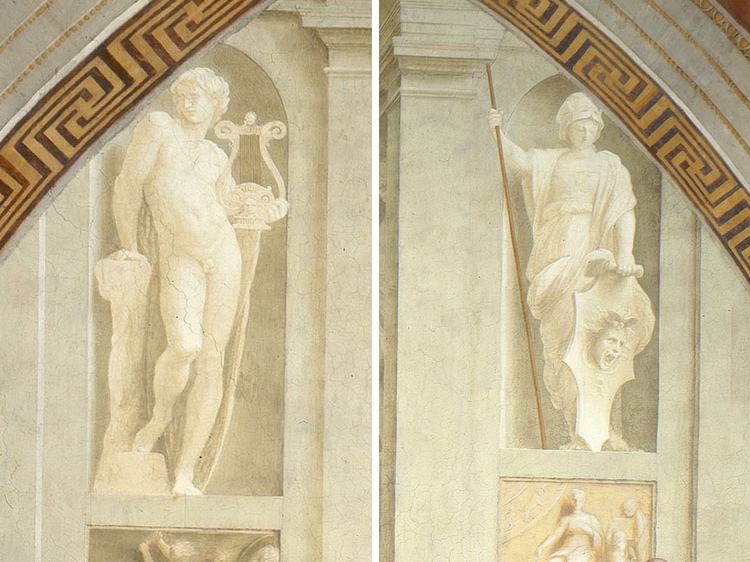

Statues

Rounding out Raphael’s program, two large statues sit in niches at the back of the school. On Plato’s right, we see Apollo, while on Aristotle’s left is Minerva. Minerva, the goddess of wisdom and justice, is an apt representative of the moral philosophy side of the fresco. Interestingly, her positioning also places her close to Raphael’s fresco about jurisprudence, which unfolds directly to her left.

Apollo, recognizable by his lyre, represents the natural philosophy side. As the god of light, music, truth, and healing, his position puts him adjacent to Raphael’s Parnassus fresco representing literature and poetry.

Since its creation, The School of Athens was a success, bringing Raphael subsequent commissions by the pope and making him one of the most sought-after artists in Rome. Though Raphael’s life was short—he died in 1520 at age 37—his impact has endured over the centuries. He’s still considered one of the great masters of the Italian Renaissance, with his work influencing artists even today.

All images via Wikimedia Commons (Public domain) except where noted.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

The History and Legacy of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mysterious “Mona Lisa”

9 Renaissance Artists Whose Work Transformed the Art World

The Significance of Botticelli’s Renaissance Masterpiece ‘The Birth of Venus'

The Significance of Leonardo da Vinci’s Famous “Vitruvian Man” Drawing

Art History: The Meaning Behind Michelangelo’s Iconic ‘David’ Statue