For millennia, humans and animals have coexisted in Africa’s Great Rift Valley, a vast geographical trench often considered to be the cradle of humankind. Home to some of the earliest hominid fossils and countless habitats, the topographical scar stretches across 11 countries on the African continent and into the Middle East, complete with deep valleys, rivers, volcanic mountains, and a chain of lakes. Here, gorillas roam through lush mountains; elephants wander across cracked deserts; leopards stalk prey in bountiful grasslands; and fish swim through rivers that end as gushing waterfalls.

More than two decades ago, Shem Compion’s fascination with the Great Rift Valley began taking shape. Since 2002, the South African photographer has descended into the region, capturing everything from endangered wildlife and dramatic landscapes to intimate portraits of local tribes in Ethiopia’s Omo Valley and other cultural groups across the Rift. No matter their setting, these photographs are a poignant reminder of the area’s diversity—and why it’s necessary to protect. After all, there is perhaps no other place in the world that has shaped humanity as much as the Rift.

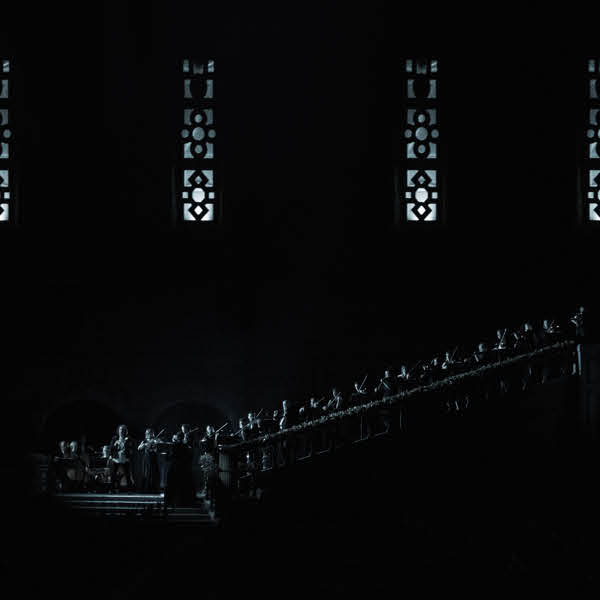

Now, after years of work, Compion has released The Rift: Scar of Africa, a monumental new volume that gathers 280 of his photographs taken throughout the region. Throughout, readers encounter aerial images of small villages peppered beneath the shadow of towering mountains; tender close-ups of women decorated with intricately beaded jewelry; and black-and-white scenes of animals traversing the natural landscape. Enriching the book are texts by over 20 anthropologists, historians, scientists, conservationists, and poets, including UN Goodwill Ambassador for the IFAD Sabrina Dhowre Elba and former Prime Minister of Ethiopia Hailemariam Desalegn, among others.

“I learned that nothing is at face value in the Rift,” Compion tells My Modern Met. “The nuance behind what we see is the real beauty of the Rift’s story that we have told.”

My Modern Met had the chance to chat with Shem Compion about his photographic practice, his new book, and how his passion for the Great Valley Rift has endured for so long. Read on for our exclusive interview with the photographer.

What first compelled you about photography as your primary artistic medium?

Early on, I discovered that the photographic process is about making a correct exposure with light, a subject, and your camera. The trick I learned was by using a creative process, you can transform that image—using the same light, subject, and camera—into something compelling, visually striking, and definitive. It’s the same elements, yet changing your perspective alters an image dramatically where the mundane can become the exceptional. When I understood this, I knew photography would be what I pursued for the rest of my career.

Why did you gravitate toward Africa’s Great Rift Valley as a photographic subject, and how has that passion endured throughout time?

As a photographer, you assimilate certain inputs that help you create great images—it is where we get the term “inspiration and feel” from. Lake Nakuru in Kenya is in the heart of the Rift. It’s a lake deep in the shadow of the Rift escarpment. The waters are filled with flamingos and surrounded by incredible wildlife. On the escarpment edge, the town is visible and three generations of my own family lived one hour away by donkey cart.

Here, the Rift is alive—it’s a living breathing organism of wildlife, conservation, and community all utilizing the same area to live in. That moment was seminal to me in understanding the significance of the Rift—to be surrounded by lions and rhinos in a forest and lake system forged by geology, while human communities also use it as part of their livelihood.

The family link forged that connection, and being amongst 60,000 flamingos also helped. From there, the passion was simple, as the Rift has so many interconnected relationships: our shared humanity, biodiversity hotspots, geological drama, and, of course, it is the greatest repository of the origin of humankind.

What was the process of creating your latest book, The Rift?

My photographic travels have helped me collect images over the last 20 years. Many images are from my safari business travels, which often focuses on Rift valley locations like the Mara/Serengeti ecosystem, the mountain gorillas, or South Luangwa. My private expeditions are where I traveled to more remote locations, searching out the magic to be made with a camera. It is here where I was most inspired.

I formally started the process of putting everything into a book in August 2021. These four years were mostly about finding the correct format of chapters and then sourcing the most appropriate contributors. One lesson I learned was how generous many of the experts were—they wanted the story of the Rift to be told. I cold e-mailed Prof. Donald Johanson, who discovered ‘Lucy’ 51 years ago and is considered the world’s most prominent paleoanthropologist. Within 48 hours, he had sent 2,000 words. I realized then that this is not my story, but the Rift’s story to tell.

Once you work with a good publisher, then the process moves quickly. It’s the foundational work at the start that is important. Once we had the chapters and contributors in place, the project moved forward easily.

The book is a celebration of the Great Rift Valley and the many people, animals, and cultures it houses. How important was site-specificity throughout the project?

It was important to me that this book was a celebration of the Rift, a project merging art and science. It covers all the significant areas of the Rift, yet intentionally does not feel the need to academically or scientifically cover every individual aspect. I did travel to site-specific locations to pay homage to the significance I wanted to showcase. Overall, we cover all the major areas of the Rift, merging compassion and science.

What was your experience collaborating with the tribes of Ethiopia’s Omo Valley and other cultural groups across the Rift Valley? Relatedly, how does your portrait photography differ from your wildlife and landscape work?

I learned quickly that you cannot engage properly with the tribal groups that interact with tourists, as the relationship is biased by Western influence. So, over time, we searched into the more remote areas and worked with tribal groups where we could build strong relationships.

With one group, the Suri, we started a mother tongue education initiative with a language NGO. In another area, with the Mursi, we focused on improving food and health security. When the relationship is mutual, rather than transactional, then you foster great human connections. I am not a photographer who wants to go into an area, take photos, and leave. I want to return and learn more, each time gleaning new experiences and making images with a deeper connection.

These initiatives have facilitated that—and it shows. Images with candor make for a great human connection and translate incredibly well in an image, which is what I seek.

What are some of your favorite stories and photographs featured in The Rift?

I invested a lot of time into an expedition to climb the volcano Ol Doinyo Lengai, for which I had great photographic ambitions. The hike up is defined as “extreme and exposed,” and as we summited, our views were thwarted by a high-powered storm, from which we had to seek shelter in a small lee. The storm raged all night, so not one photo was taken and upon daylight we scampered down the volcano depressed and despondent, my dreams of photo glory whipped away in the wind. Descending into a beautiful day, I noticed the amount of Maasai life around the volcano. Small village huts, daily life in the shadow of the volcano, and the context of the volcano in the environment—not of the landscape, but of the people, too. These are the images in the book today. It was a great lesson not to focus on the lava of the volcano when the narrative is the context of where the volcano stands.

I returned to this same volcano this year to photograph the recently discovered 10,000-year-old Enkaro Sero footprints at its base. Captured in cooling lava, these footprints give incredible ethnographic information about our human ancestors. It’s another indication that the narrative around the subject is more important than the subject itself.

Another story I love is my time with the Turkana, who are a fishing group eking out a living on an austere landscape where lava rock meets the jade sea. There are many Turkana images in the book. The beadwork of the ladies is probably the most impressive of all the Rift valley tribal groups. The difficulty is in showcasing it at its best. Once I discussed more with the ladies, I learned these beads are not simply like earrings. They represent generational inheritance, strands handed down between mothers and daughters over time, each one telling a story. The beadwork we see represents marital status, wealth, age set, fertility, all signatured with some individual flair. The beauty is in the design, and, once abstracted, the detail becomes the story.

I learned that nothing is at face value in the Rift—the nuance behind what we see is the real beauty of the Rift’s story that we have told.

What do you hope people unfamiliar with the region will take away from The Rift?

I hope that a reader can open up any page of the book and feel the significance of the Rift and be connected to it. Visitors may think they are on safari to see lions and elephants, yet they can open the book to see that the place they are in is so much more than the animals they came to see.

If this book can show the interconnectedness of this geological scar where culture, conservation, geology, and origin all collide, then I believe it will have made its mark. The paradox of the Rift is that the scar tearing Africa apart is the same binding fabric of Africa’s great elements.