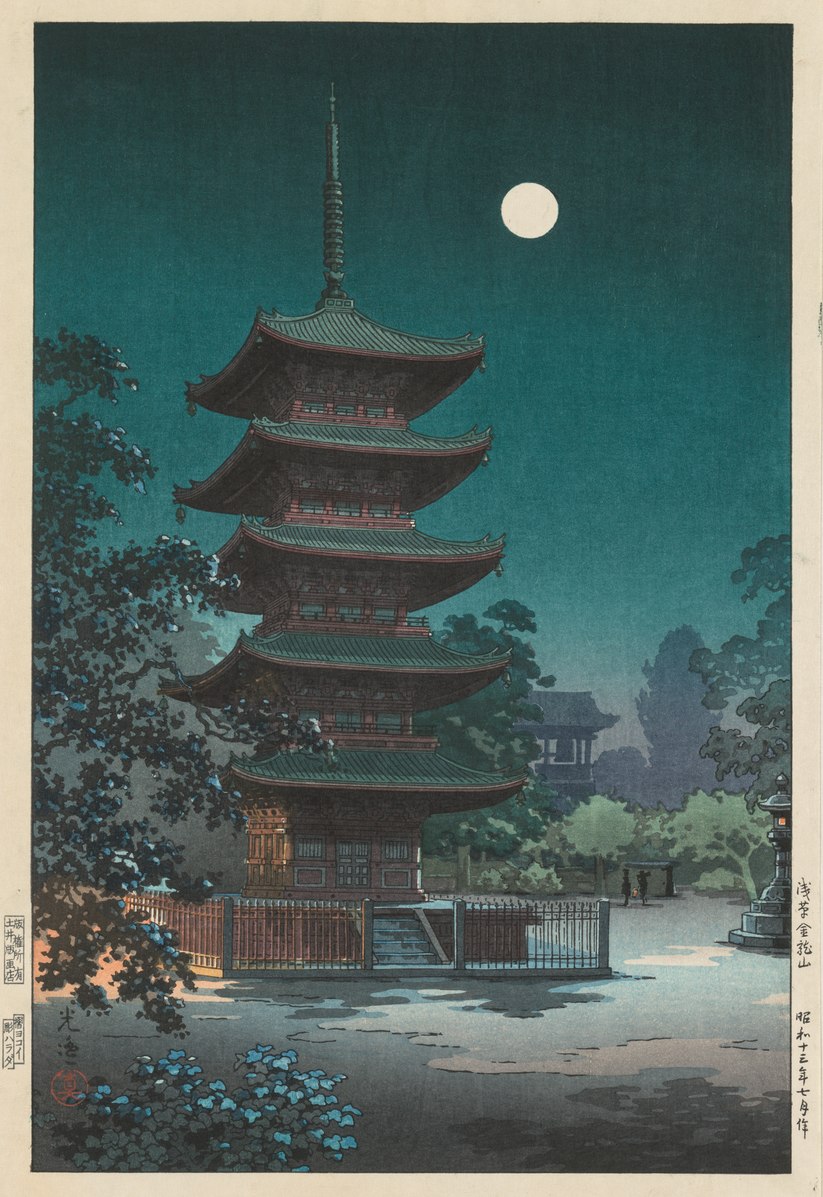

“Sketches of Famous Places in Japan: Asakusa Kinryūzan Temple,” 1938. (Photo: Cleveland Art via Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0)

In the early 1900s, Japan had undergone some dramatic changes. Just a few decades before, the country had opened itself up after more than 200 years of self-isolation, and the dual forces of industrialization and internationalism had begun taking root. It was within this shifting environment that Japanese artists revived ukiyo-e, a traditional form of woodblock printing, as shin-hanga (literally meaning “new prints”). Unlike ukiyo-e, though, shin-hanga artists incorporated Western techniques and elements, offering a more contemporary—and romanticized—glimpse into Japan’s past.

At the center of this art movement was Tsuchiya Kōitsu, one of the few students of the famous Meiji-era print designer Kobayashi Kiyochika. Born in 1870, Kōitsu became known for his vibrant landscape prints, a passion he only developed later in his career, at the age of 61. From the early 1930s until 1940, he designed and produced landscapes for some of Japan’s most renowned woodblock print publishers, including the Tokyo-based Kawaguchi and Watanabe. Factoring into his success was his chance encounter with Watanabe Shōzaburō, who is largely credited as the founder of the shin-hanga movement, in 1931.

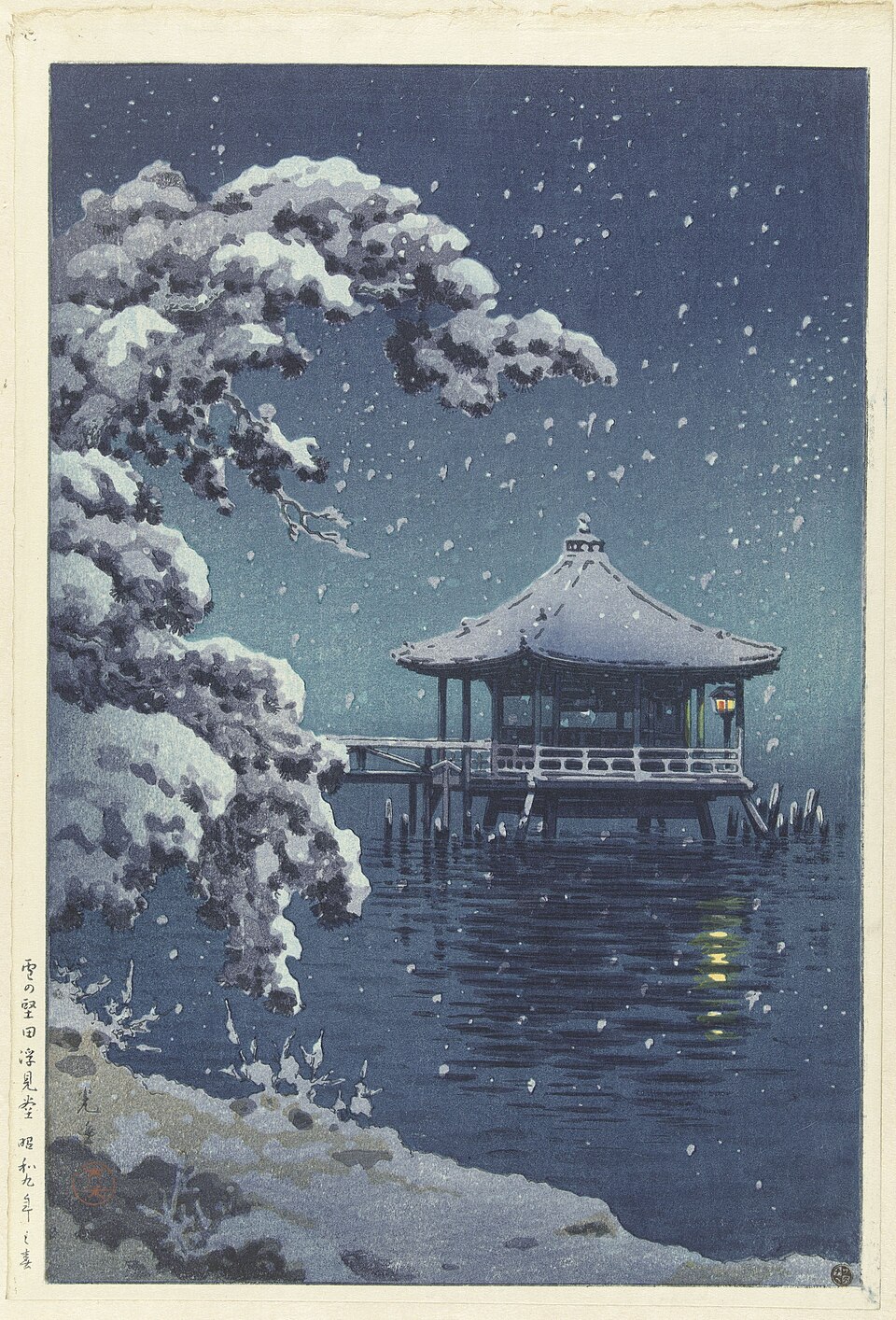

Like many shin-hanga artists, Kōitsu favored illustrative compositions, featuring precise linework and “quintessentially Japanese” sights, such as famous pagodas and temples, to increase international appeal. But what distinguished Kōitsu’s practice was his treatment of color. His landscapes often hum with bright colors and dramatic lighting effects, resulting in propulsive and highly saturated atmospheres. One print from 1937, for instance, showcases the Nagoya Castle, constructed in 1612 during the Edo period. The castle and its surroundings are steeped in bold tones, where every color is heightened to its extreme. Cherry blossoms are a deep, rosy shade, tinted with purples and blues; the trees are emerald green, with hints of turquoise; and the sky slowly fades from pink to a deep blue as the eye progresses up the canvas.

Kōitsu also rendered evenings and nights masterfully. His print of Asakusa Kinryūzan Temple brilliantly combines greens, blues, and purples to elicit a sense of quiet tranquility, while a rainy scene of Kofukuji Temple seems appropriately dreary with its grayish-green palette. These various colors and moods seem reminiscent of those found throughout manga, even though the art form was developing independently from and earlier than shin-hanga.

In 1949, at 79 years old, Kōitsu died from complications due to pneumonia. Despite only producing his landscape prints for about a decade, the artist still had a tremendous impact on the shin-hanga movement and the Japanese art that followed.

Tsuchiya Kōitsu was a significant figure in Japan’s shin-hanga movement, which revived traditional ukiyo-e prints.

“Snow on the Ukimido at Katada,” 1934. (Photo: Rijksmuseum via Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0)

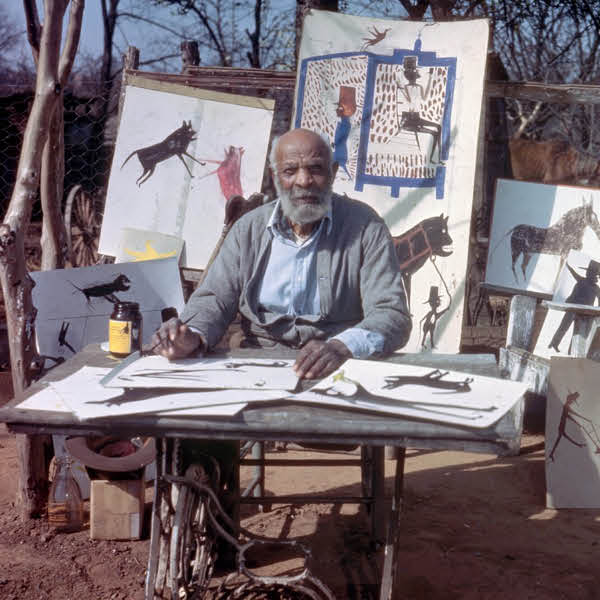

Portrait of of Tsuchiya Kōitsu (1870-1949) in March 1902. (Public domain)

Kōitsu specialized in landscape prints, complete with highly saturated colors, precise linework, and dramatic lighting effects.

“Rain at Kofukuji Temple,” 1937. (Public domain)

Some have even drawn aesthetic similarities between Kōitsu’s style and that of manga, which was developing independently from and earlier than shin-hanga.

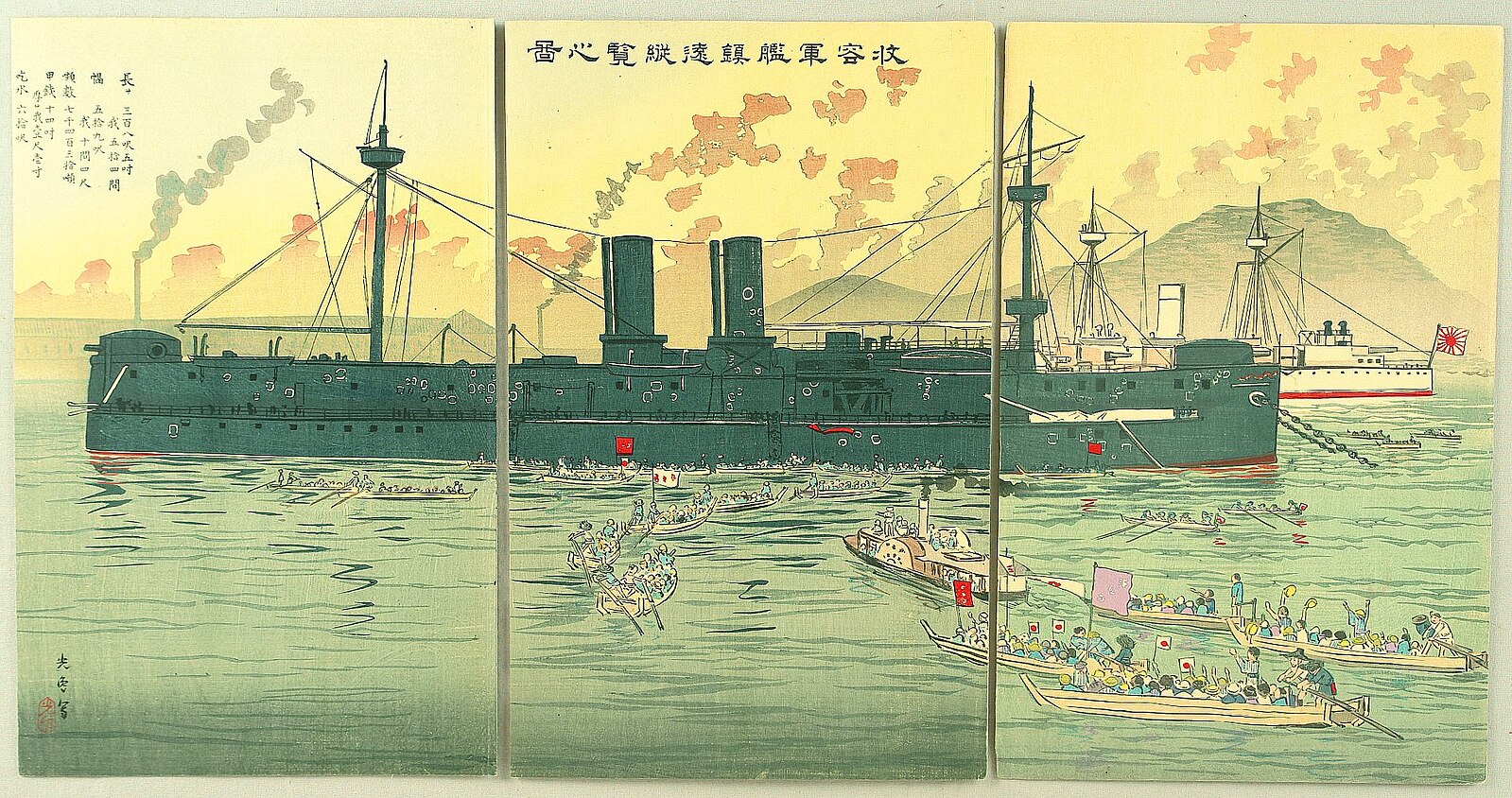

Chinese Warship Ting Yuang Visiting Japan. (Public domain)

Sources: Tsuchiya Kōitsu (1870-1949); Reflections of a Changing Japan: The Evolution of Shin Hanga; Shin-hanga; Tsuchiya Koitsu; Koitsu Tsuchiya (1870 – 1949)

Related Articles:

Discover How Japanese Swordsmiths Transform Sand Into Legendary Katanas

Takashi Murakami Reinvents Japanese Art History in Upcoming Gagosian Exhibition

Illustrator Reimagines Avengers Endgame Characters as Ukiyo-e Japanese Warriors