Memorial Portrait of Utagawa Hiroshige by Utagawa Kunisada, 1858. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Japanese artist Utagawa Hiroshige is often regarded as the last great artist of the Ukiyo-e movement. Ukiyo-e translates to “images of the floating world,” and artists of the movement made woodblock prints and paintings that depicted scenes of history, nature, and famous faces of Edo. However, rather than create prints depicting typical Ukiyo-e motifs, Hiroshige developed his own style. He looked to the everyday experience for inspiration, rendering images of working men and women in urban environments. He created his images with such skill, that day-to-day scenes were transformed into captivating landscapes with vibrant colors and charming details.

Hiroshige’s prints appealed to the masses, as the Japanese public were able to relate to the scenes. Many of his artworks focused on seasonal weather conditions or festivities that marked a specific time of year. Still popular today, Hiroshige’s woodblock prints offer a lasting record of the bygone Edo period.

Read on to discover 10 facts about the legendary Japanese Ukiyo-e artist, Utagawa Hiroshige.

“Station of Ōtsu” by Utagawa Hiroshige, c. 1840. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0)

Full Name | Utagawa Hiroshige |

Born | 1797 (Edo, Japan) |

Died | October 12, 1858 (Edo, Japan) |

Notable Artwork | One Hundred Famous Views of Edo |

Movement | Utagawa school |

He had many names

Hiroshige was born in 1797 and was the only son of Andō Gen'emon. He was originally named Andō Tokutarō, but his name changed throughout his childhood—he was also known as Jūemon, Tokubē, and Tetsuzō.

His childhood was tragic

Hiroshige’s family were Samurai, meaning they were the highest ranking of the four Japanese castes. Due to their social class, the Andō family were expected to uphold their ancestral positions as fire wardens in the civil service. They lived in the Yayosu Riverbank area of Edo (now known as Tokyo), which had become capital of the Japanese empire in 1603.

When Hiroshige was three years-old, his older sister passed away. Then in 1809, when he was 11, his mother died. His father died several months later, just after his 12th birthday. Hiroshige became an orphan and had to fend for himself.

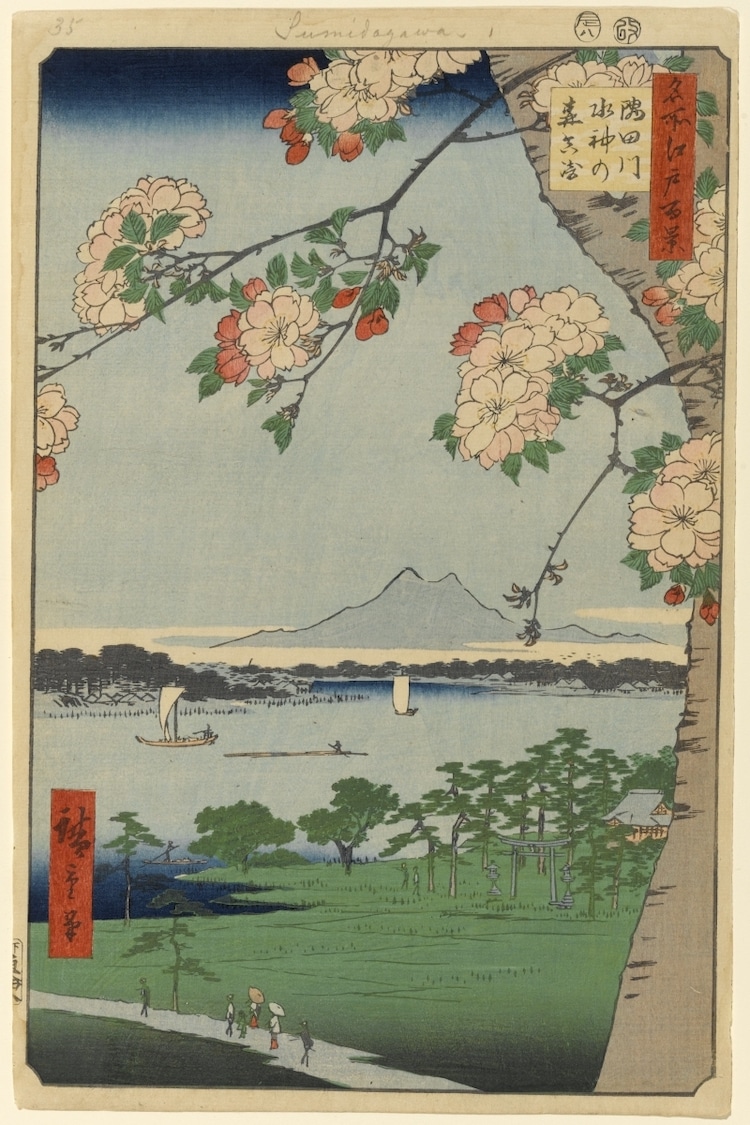

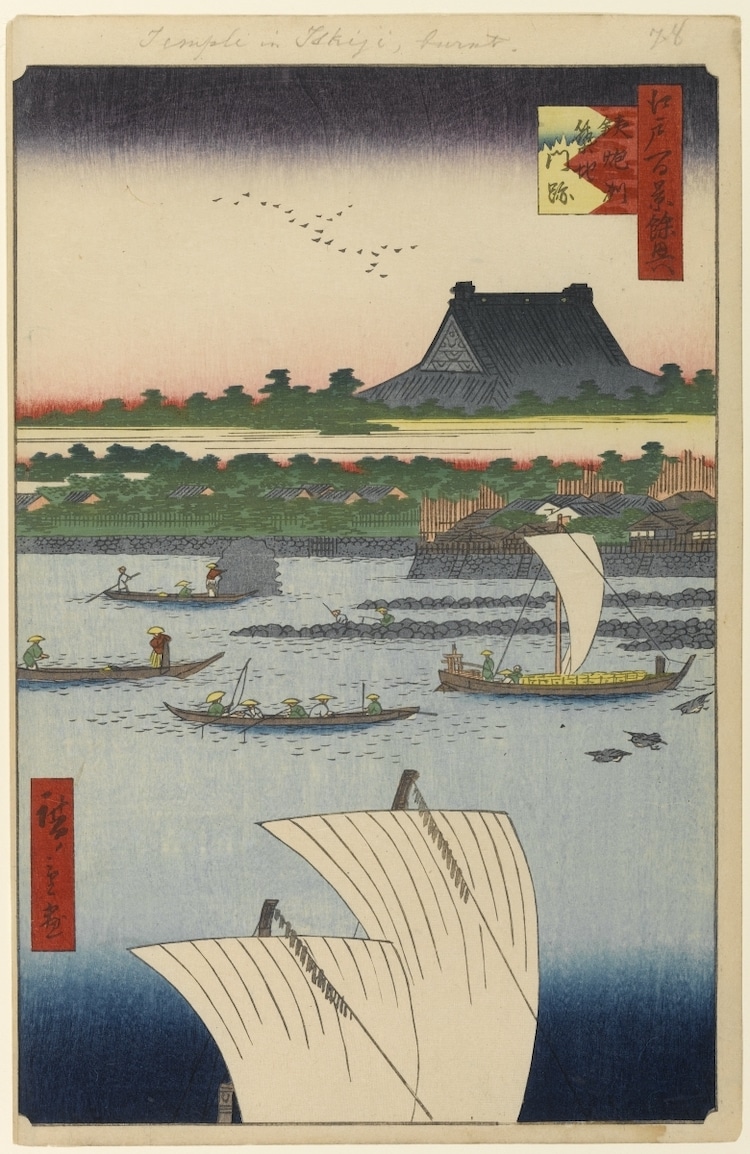

“Suijin Shrine and Massaki on the Sumida River.” Part of the series, “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo,” no. 35, 1856. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

He was a fireman before an artist

After his father died, Hiroshige inherited his father’s role of fire warden of Edo castle. The job provided him enough income to survive, but it also provided him with a lot of free time. Those working in the fire service often pursued other hobbies and occupations alongside their civil service job. Hiroshige took up art, and enrolled under Japanese ukiyo-e artist Toyohiro of the Utagawa school. Hiroshige also studied at Kanō school, one of the most famous schools of Japanese painting.

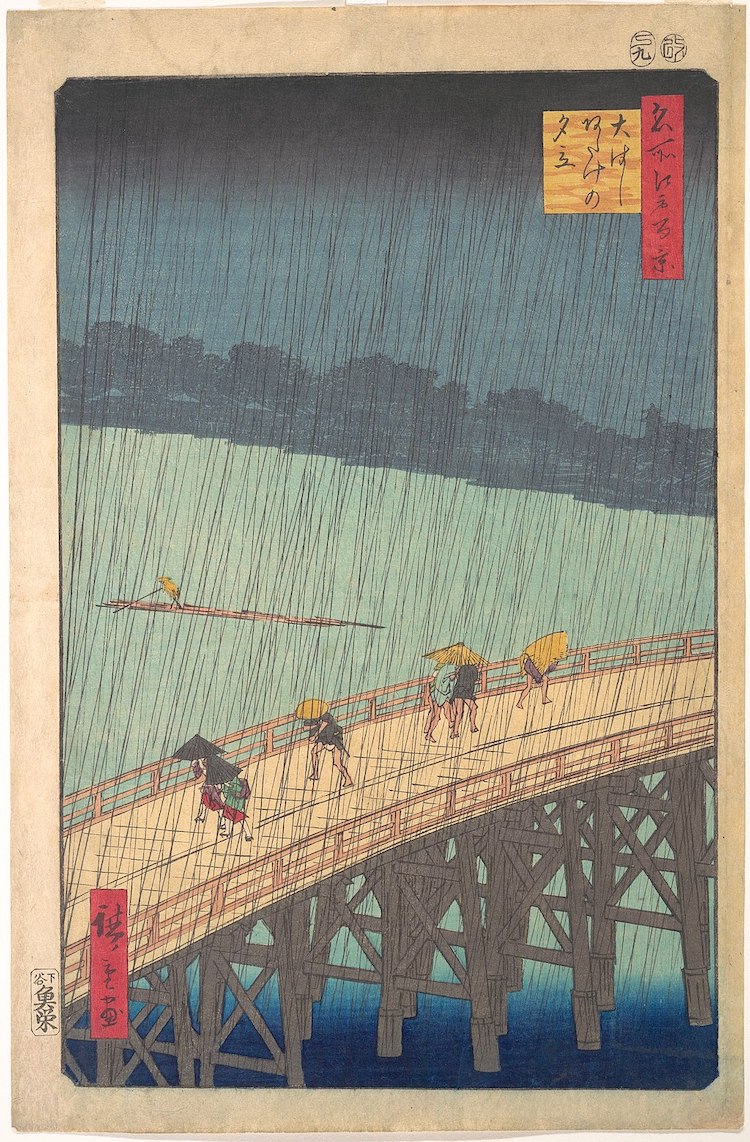

He was a master of bokashi

Hiroshige was known for his woodblock prints that featured beautiful skies in saturated color gradients. He achieved the subtle variation in hue using the ukiyo-e bokashi technique. This involved using a brush to apply ink in multiple colors to different sections of a moistened printing block. The ink bleeds across the wet area, creating a soft gradation when printed on paper.

“Teppozu and Tsukiji Honganji Temple.” Part of the series, “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo,” no. 78, 1858. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

He inspired famous European artists

Hiroshige’s prints helped popularize Japanese art around the world. In Europe, artists of the 19th century were fascinated by his use of color and his ability to capture the passing of time. French Impressionists Édouard Manet and Claude Monet were known as fans of his work. And some art historians have noted that Post-Impressionist Paul Cézanne’s use of perspective is similar to that in Hiroshige’s The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. Even Vincent van Gogh created a tribute to Hiroshige's Sudden Shower Over Shin-Ohashi Bridge and Atake with his 1887 painting, Bridge in the Rain.

He created around 8,000 works

Hiroshige was extremely prolific throughout his life and produced more than 8,000 works. His earliest prints depicted common ukiyo-e themes such as women and actors. However, in 1831 he began focusing on landscape art. He created numerous print sets inspired by the beauty of Edo, the changing seasons, and his travels around Japan.

“Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake.” Part of the series, “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo,” no. 52 or 58, 1857. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

He produced a series of prints that document his journey along the imperial road, Tōkaidō

Hiroshige's first major print series was The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō. It depicts a trip the artist took in 1832, where he travelled the entire length of the imperial Tōkaidō road. The journey is one of the most important of the Five Routes of the Edo period, connecting Kyoto to Edo. There were 53 post stations along the route to Kyoto, and Hiroshige stopped at each one to sketch the scene. When he returned home, the artist immediately began work on the first prints from the series. He presented the landscape prints to publishing houses, and they soon became some of his best-selling works. The success of The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō series established Hiroshige as the most successful printmaker of the time.

“Hodogaya (Shinkame Bridge),” in “The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō (Road) (Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi no uchi),” c. 1834 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

His One Hundred Famous Views of Edo series is one of the most famous collections of Japanese art

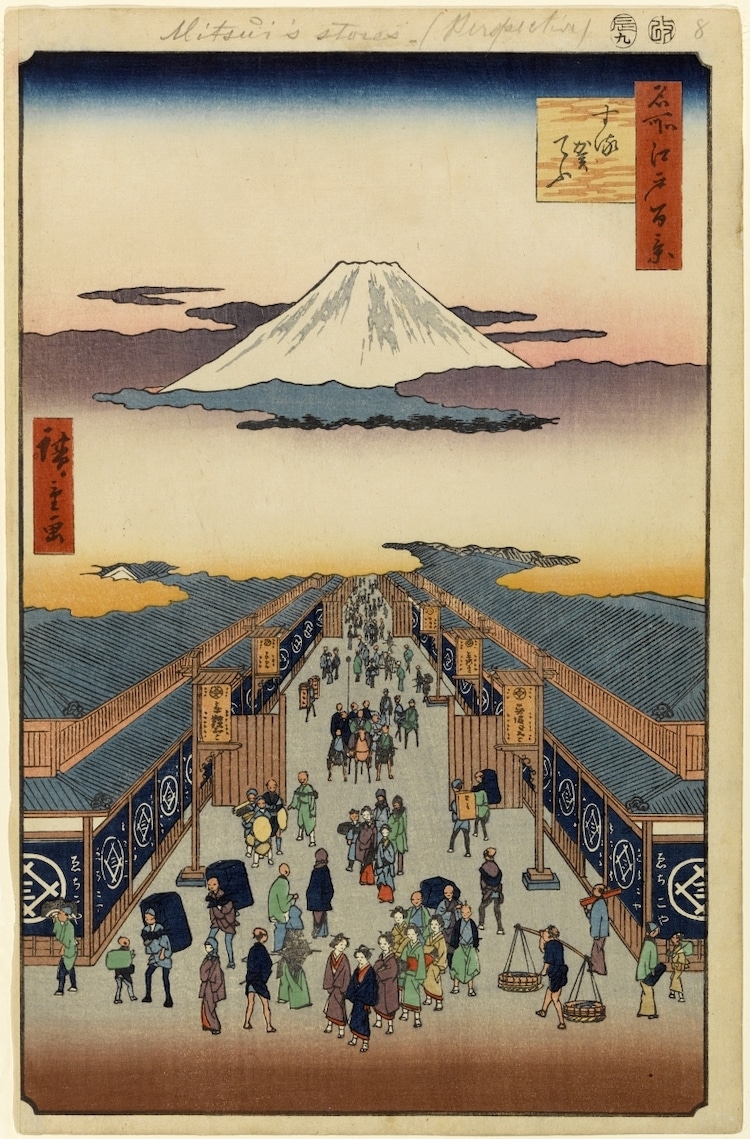

In 1856, Hiroshige began his influential One Hundred Famous Views of Edo series. Rendered in his distinct style, the prints depict the shrines, famous stores, restaurants, and tea-houses of Edo, as well as the Sumida river and its surrounding landscape.

Unfortunately, Hiroshige died before he could complete the collection and his work was continued by his son-in-law, Hiroshige II. The finished series was published between 1856–59 and was hugely popular. The images from the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo are still some of the most sought after woodblock prints of all time.

Part of the series “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo,” no. 008 , part 1: Spring, 1856 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

He lived in poverty

Despite being a successful artist, Hiroshige never became wealthy. He earned only around twice the salary of a laborer. Some people believe this is why he produced so many artworks. He worked tirelessly to make ends meet, and he even had to leave behind instructions on how to pay his debts after he died.

He became a Buddhist monk

In 1856, Hiroshige “retired from the world” and became a Buddhist monk. He died two years later in his early 60s and was buried in a Zen Buddhist temple. Hiroshige passed away during the great Edo cholera epidemic of 1858, however, it’s still unclear if the disease was the cause of his death. Before he died, Hiroshige wrote this farewell poem:

“I leave my brush in the East,

And set forth on my journey.

I shall see the famous places in the Western Land.”

Related Articles:

The Unique History and Exquisite Aesthetic of Japan’s Ethereal Woodblock Prints

The History of ‘The Great Wave’: Hokusai’s Most Famous Woodblock Print

200 Japanese Woodblock Prints From Over Two Centuries in One Book

How to Make Your Own Woodblock Print Like the Japanese Masters