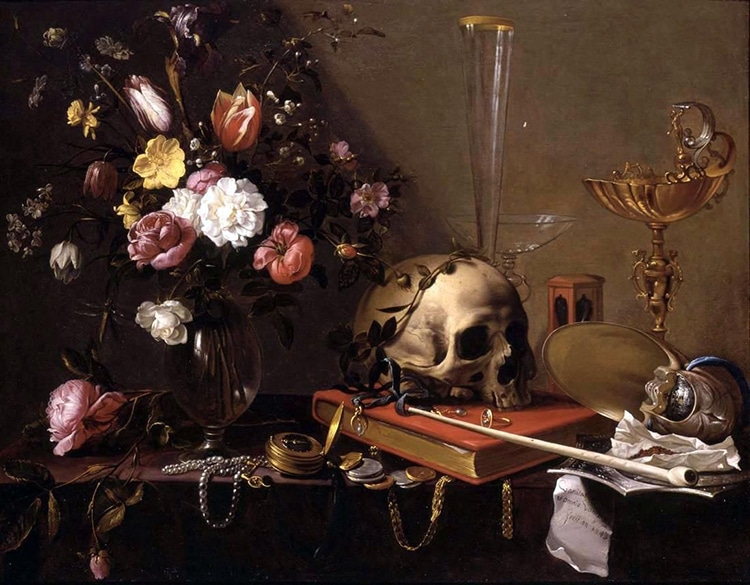

“Allegory of Vanity,” by Antonio de Pereda, circa 1632 – 1636. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

What does a skull symbolize? Many people would say death or danger, pointing to the classic “skull-and-crossbones” pirate flag. Others might think first of skulls in a scientific context—an evolutionary trail leading humans to our modern form. But to many painters in the 17th century, the skull was a symbol of the fleeting nature of life. A particularly popular motif among the Dutch Old Masters, skulls were incorporated into a genre of painting known as vanitas.

The vanitas painting tradition takes its inspiration from the Bible, but artistic meditations on fleeting life and impending death date back to ancient times. Symbols—such as wheels, hourglasses, and clocks—represent the unstoppable passage of time. However, vanitas paintings are not all doom and gloom. Instead, they encouraged a more pious, spiritual approach to life. Those viewing an early modern vanitas painting were encouraged to live their lives transcendent of earthly concerns.

Memento Mori

A Roman mosaic “memento mori” from Pompeii, showing the Wheel of Fortune and life and death both hanging by a thread. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The ancient Greeks and Romans thought a lot about death. Philosophers such as Socrates and Plato mused that each individual's end was inevitable. Stoicism incorporated this truth as it developed as an ancient philosophy. A memento mori served as a physical reminder of this truth. These tokens are literal embodiments of their Latin name, meaning “remember that you will die.” Such a reminder could take the form of a mosaic. A skull was usually center stage, but symbols such as the wheel of time or vegetation (which naturally wilts) were also used.

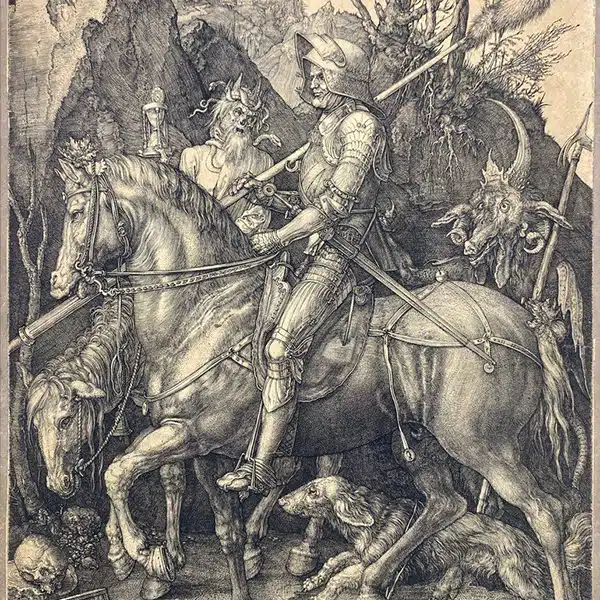

Medieval Europeans combined Christian theology with the stoic legacy to put their own spin on memento mori. Still focusing on impending death, they incorporated symbols such as hourglasses, extinguished candles, flowers, and fruit. Each item is—like human life—inevitably “ended” in some way—either by a swift gust of air, naturally passing time, or decay. Other symbolic memento mori representing meditations on life and death can be seen around the world from Mexico to Tibet.

Dutch Golden Age

“A vanitas portrait of a lady,” Clara Peeters, circa 1613-1620. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

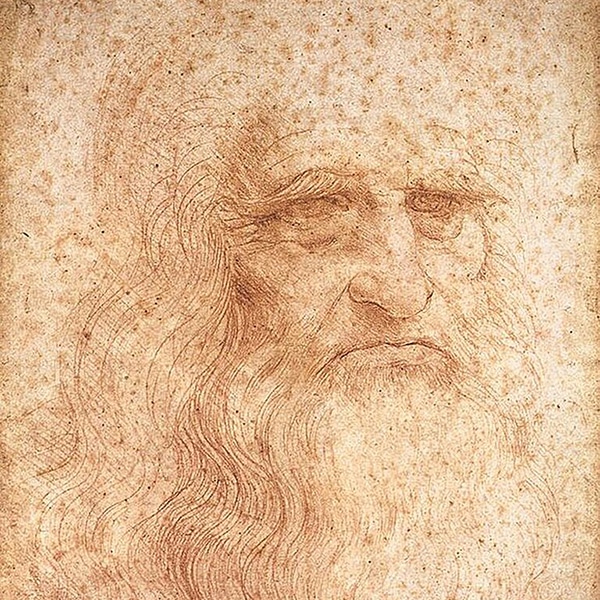

The memento mori was embraced by the painters of the Dutch Golden Age. The Golden Age spans the 17th century when trade allowed the Netherlands to flourish. Art and culture thrived under the prosperous patronage of merchants and nobles. Painters such as Rembrandt van Rijn, Johannes Vermeer, and Frans Hals produced countless works of portraiture, still life, and landscape. Known for the subtle brushwork and striking realism of the Baroque period, the works of the Dutch Old Masters today fetch incredible prices at auction.

Beginning in the 16th century and continuing into the 17th century, a group of painters centered around the Dutch city of Leiden began to produce distinctive vanitas paintings. The city was very Protestant, and the artificial pleasures of this life were heavily emphasized by the theologians who studied at the University of Leiden. The birthplace of Rembrandt, the city was also a center of the Dutch Renaissance. Theology and artistic tradition would come together to produce countless well-known examples of vanitas paintings.

Vanitas, A Meditation

“Vanitas—Still Life with Bouquet and Skull,” by Adriaen van Utrecht, circa 1642. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

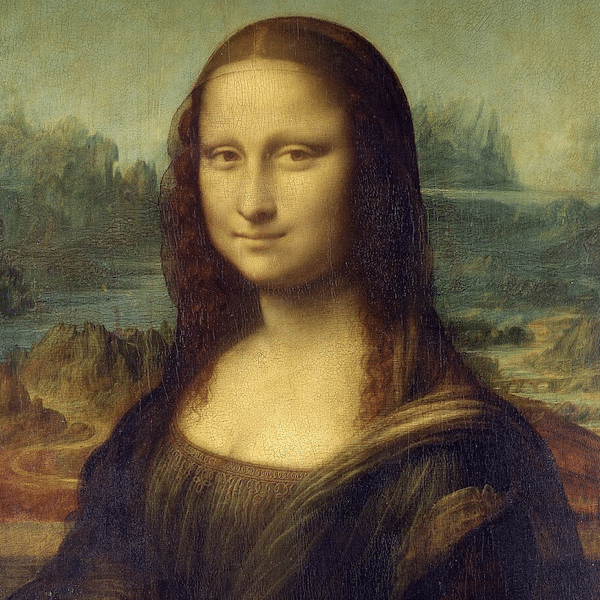

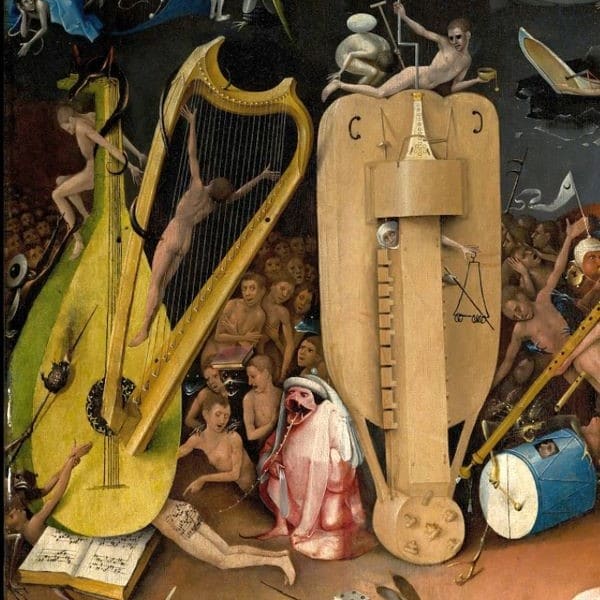

The vanitas genre is, in some ways, a subset of the ancient memento mori tradition. Vanitas takes its name from the Book of Ecclesiastes in the Bible, “Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities, all is vanity.” Like memento mori artwork, skulls feature prominently, as do hourglasses and withering vegetation. These carry the same meaning—life is short and fleeting. However, as noted by the Tate, vanitas paintings add a more worldly symbolism. Gold, jewels, wine, books, and musical instruments all remind the viewer that these earthly pleasures are worthless or in vain.

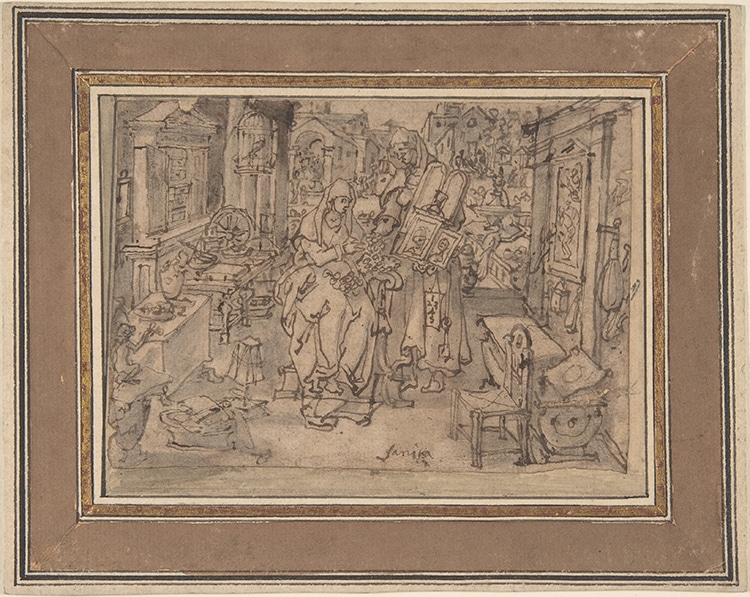

“Vanitas,” by Jan van der Straet, called Stradanus, mid-16th to early-17th century. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public domain)

While vanity is often used to mean prideful or conceited, here it refers to the fallacy of placing trust and enjoyment in worldly activities. Instead, the viewer is encouraged to contemplate the eternal afterlife as described in Christian theology. Protestant painters produced many of the most well-known vanitas works. However, Catholic artists contemplated these same themes as well. Reminded of impending death and the futility of their own secular accomplishments, any viewer was encouraged to reexamine their relationship with God as their savior and only hope. While not a strictly cheerful message, all hope was not lost for the pious.

“Allegory of Charles I of England and Henrietta of France in a Vanitas Still Life,” anonymous Flemish painter, 1670s. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Vanitas works are an example of allegorical art. An allegorical work may be figurative or still life, however, its true meaning goes beyond what is depicted. The subject of the work is used to represent a higher ideal or idea. These hidden meanings may sometimes seem obscure to the contemporary viewer. However, a viewer at that time would have shared much of the same religious and cultural lexicon as the painter. A vanitas work featuring a skull, hourglass, and abundant flowers would have clearly communicated its thematic meaning to a 17th-century Dutchman.

Modern Vanitas

“Skull Portraits,” by Alexander de Cadenet, on view at 30 Underwood Street Gallery, Shoreditch, London March 2000. (Photo: Saffarelli via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

This shared cultural lexicon is still in use today—even as relevant symbols have morphed over time. Most enduring is the skull, still today a symbol of death. Modern artists have incorporated the skull into their works, many of which can seen as continuations of the Vanitas tradition. British artist Alexander de Cadenet‘s celebrity skull portraits using x-rays are a contemporary example. Damien Hirst‘s For the Love of God is another example. Described as a sort of “counter-vanitas,” or a triumph over death, the work is a platinum cast of an 18th-century human skull encrusted with over 8,000 diamonds. The teeth are real human teeth. The work debuted in 2007 to much comment in the art world.

Art is arguably about life, and commenting on death is not new. The vanitas tradition continued the meditation of life and death that had long existed in memento moris. Through painting and modern media, artists have stared death in the face and asked questions about how we should live our lives before that moment comes. While some may see vanitas works as ghoulish, the early modern painters and their viewers saw a message of hope. No matter how transient this life, the paintings illustrate, there is something higher to aspire towards.

“Still-Life with a Skull, Vanitas,” by Philippe de Champaigne, circa 1671. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Related Articles:

Discover 10 Famous Portrait Paintings and the Real Life People Who Inspired Them

Japanese Artist Plants Colorful Flower Landscapes to Explore Nature’s Cycle of Life and Death

How American Benjamin West Became London’s Preeminent Painter During the American Revolution

How Delacroix Captured France’s Revolutionary Spirit in ‘Liberty Leading the People’