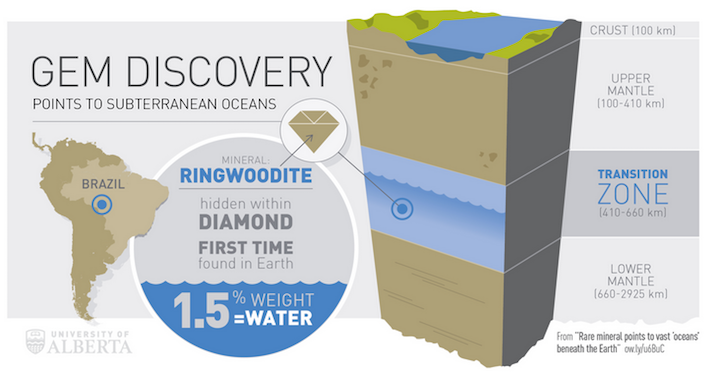

Researchers believe that deep below the Earth's surface lies an ocean of water. This might sound like something straight out of a science fiction movie, but thanks to a tiny, extremely rare gemstone, there's cause to believe the seemingly impossible exists. The special stone is called ringwoodite, and its chemical makeup holds the clues to what's potentially located hundreds of miles beneath the soil.

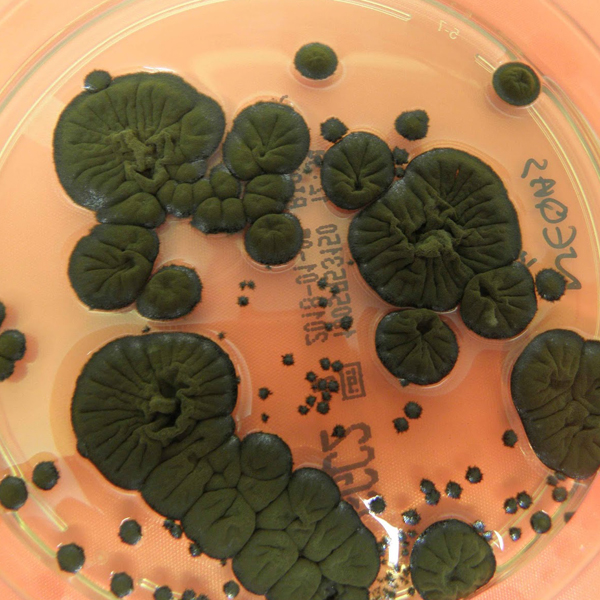

Ringwoodite is formed when olivine, a material abundant in the mantle, is highly pressurized and very hot. (When it's in less-pressurized environments, it reverts to olivine.) Scientists have seen ringwoodite in meteorites and created it in a lab, but until now, had never found a sample from Earth.

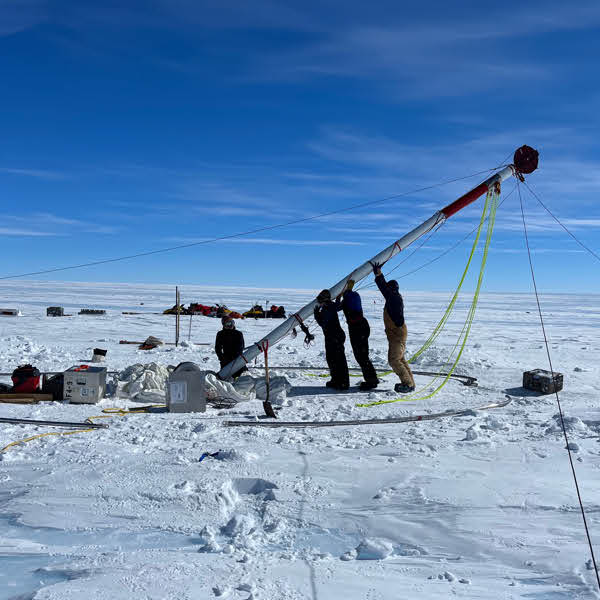

While there were theories about an underground ocean before, diamond expert Graham Pearson of the University of Alberta helped advance the hypothesis. A few years ago, he came across the three-millimeter brown diamond while was researching another type of mineral. Pearson and his team discovered that 1.5 percent of the ringwoodite's weight comprised trapped water. The findings, published in the science journal Nature, analyzed the mineral's depth, which would suggest that there's a lot of water below the surface.

Above image credit: Richard Siemens / University of Alberta

Image credit: University of Alberta

Image credit: University of Alberta

Earth is made up of several layers. At the top is the crust, which reaches about 100 kilometers down and contains the deepest depths of our known oceans. The upper mantle is underneath the crust and extends about 300 kilometers deep. Beyond that section is known as the “transition zone”–this is where the ringwoodite is from. Scientists debate what this area is, exactly: some contend that our oceans' water originated there, while others say it's dry.

Pearson's paper alters the discussion, and he says that there are two possible explanations for water in the ringwoodite. One is that extreme pressure and its chemical makeup spontaneously created the water. “Alternatively,” Pearson wrote in Nature, “the ringwoodite is ‘protogenetic,' that is, it was present before encapsulation by the diamond and its water content reflects that of the ambient transition zone.” In other words, the water was already there and the gemstone absorbed part of it.

Like many scientific breakthroughs, the discovery of ringwoodite was luck. According to Hans Keppler of the University of Bayreuth in Germany, a volcanic eruption (or something similar) probably pushed the mineral to the surface of Mato Grosso, Brazil. It was a fantastic coincidence that Pearson was able to analyze the ringwoodite before it transformed back into olivine.

Graham Pearson: Nature

via [Motherboard]