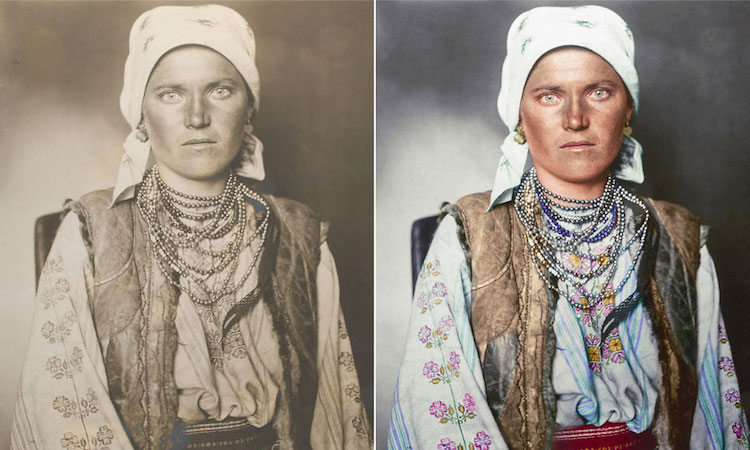

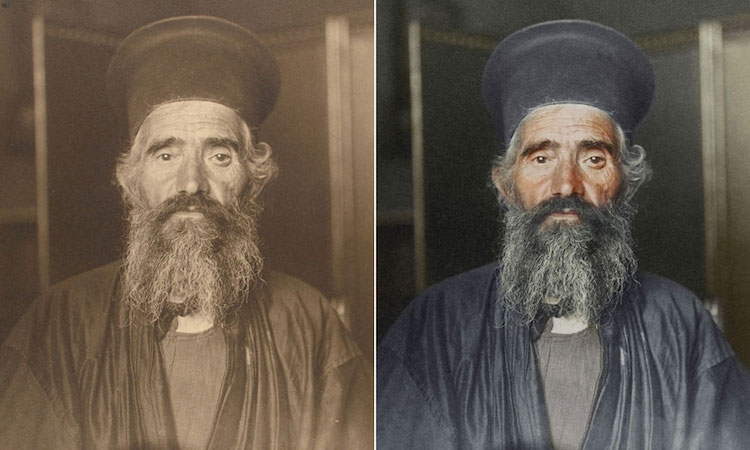

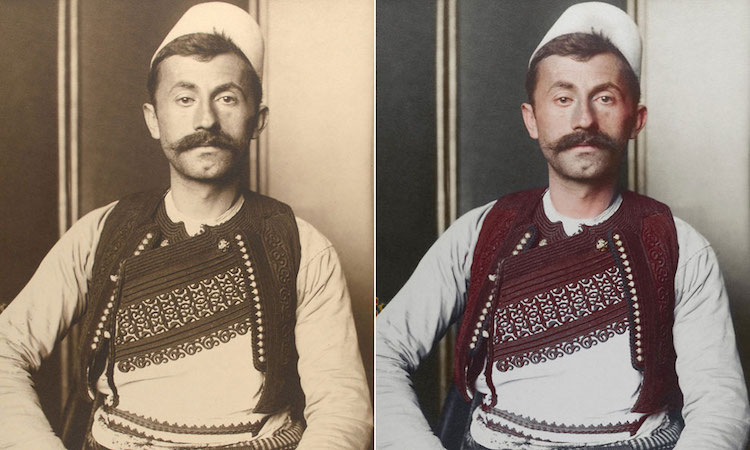

Between 1892 and 1954 more than 12 million men, women, and children passed through New York's Ellis Island as they hoped to begin a better life in the United States. Amateur photographer and chief registry clerk Augustus Francis Sherman photographed many of these immigrants, dressed in their finest clothing, between 1906 and 1914. Often wearing clothes that exemplified the national dress of their countries, the portraits demonstrate the huge range of immigrants who passed through Ellis Island. In fact, today it's estimated that more than one third of Americans have an ancestor who passed through Ellis Island.

Jordan Lloyd of Dynamichrome, painstakingly researched the history of these costumes, using postcards, historical references, and color images from later photographers to accurately bring color to the portraits. Activating the national dress through color creates a new link to the past, reminding us of the diversity upon which America was built. The portraits are just some of the 130 historical photographs that will be published in The Paper Time Machine, a book collaboration between Lloyd and Wolfgang Wild of Retronaut that is currently being funded on Unbound.

Above: A Ruthenian woman, circa 1906. The region of the kingdom of Rus incorporates portions of modern-day Slavic speaking countries. Her dress is embroidered with traditional flora patterns.

An Italian woman, circa 1910. This long, homespun dress would have covered her ankles, with the top tied in a way to expose a portion of the blouse. The materials would have been regional, with shawls and veils a common feature.

An Algerian man, circa 1910. His kaftan tunic is common of many cultures and was often made from wool, silk or cotton. He also wears a kufiya, a square of fabric folded into a triangle and set upon his head by an ‘iqual, a circle of camel hair

A Laplander, circa 1910. The Sámi people inhabited the Laplands, a cultural region that stretches over four countries, from Norway to Russia. The portrait shows a traditional costume, the Gátki, which was made from reindeer leather and wool, and was used both in ceremonial contexts and as working dress.

A Norwegian woman, circa 1906-1914. Bunad is a term that encompasses traditional Norwegian dress, though each region has distinct dress depending on tradition and available materials. In rural areas, clothes were often homemade and either elaborate or sparse depended on their intended use. Covered hair was a sign of marriage for many women in rural Norway.

A Romanian piper, circa 1910. His embroidered sleeved sheepskin coat—called a crojoc—is far less elaborate than a shepherd's version, demonstrating his position as working class. He is also wearing a pieptar, a waistcoat worn by both men and women.

A Danish man, circa 1909. The Danish had a tradition of dressing in simple, homemade clothing often in cuts and colors that were regional and limited according to the vegetable dye available. The presence of silver buttons and detailing was an indicator of an individual's wealth.

A Dutch woman, circa 1910. The characteristic white bonnet was typically made from white cotton or lace and often came with a cap. The colorful tunic, embroidered with floral motifs, covered the dark sleeved bodice.

Rev. Joseph Vasilon, Greek-Orthodox priest, circa 1910. The portrait is a testament to that fact that Greek-Orthobox vestments have remained largely unchanged. The priest wears an ankle-length cassock called an anteri under an outer cassock known as a exorason and a kalimavkion, a cylindrical hat worn during services.

An Albanian soldier, circa 1910. The soldier wears a qeleshe, a felt cap whose shape was largely determined by region. Based on the cut and color of his vest, known as a jelek or xhamadan, he most likely from the northeastern regions of Albania. The vest was decorated with embroidered braids of silk or cotton, with color and decoration signifying the region and social rank of the wearer.

A Guadeloupean woman, 1911. Her ornamental headpiece, again a signifier of marital status, can be traced to the Middle Ages. Made from Madras fabric exported from India with a pattern influenced by the Scottish in colonial India, it eventually made its way to the French-occupied Caribbean.

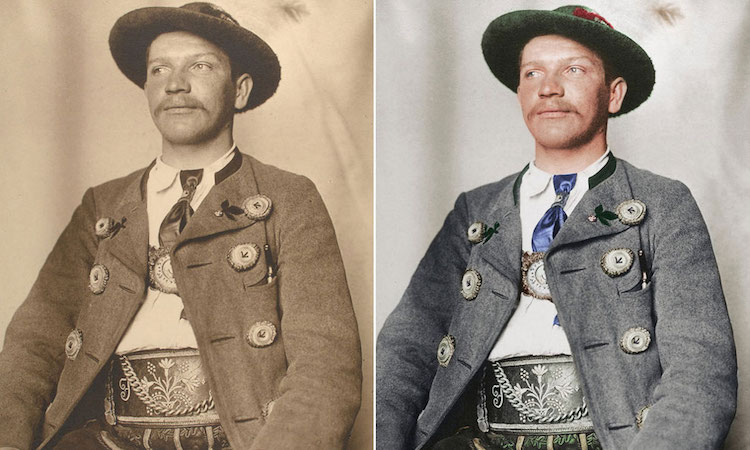

A Bavarian man, circa 1910. Lederhosen were regularly worn in rural areas of alpine Germany. The jacket, known as a trachtenjanker, was made from wool and decorated with horn buttons. It was a jacket typical for Bavarian hunters.

A Romanian shepherd, 1906. He wears a sarica, a traditional shepherd's cloak made from three or four sheepskins sewn together. It typically flowed beyond the knee and could be used as a pillow when sleeping outdoors.

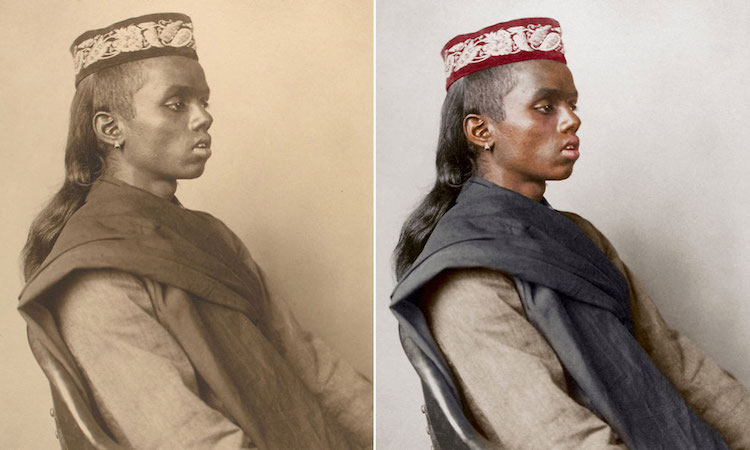

A Hindu boy, 1911. His cap, or topi, was worn across the Indian subcontinent with many regional variations. It was especially important to the Muslim community, where is was known as a taqiyah.

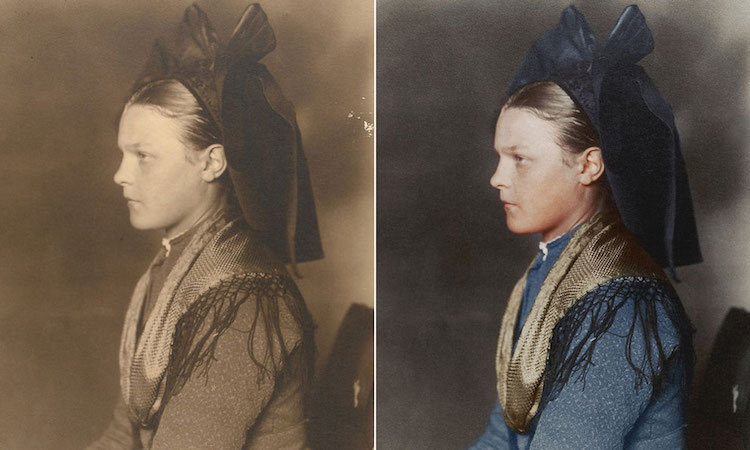

An Alsace-Lorraine girl, 1906. From Germanic-speaking Alsace, now France, she wears a schlupfkàpp, a large bow that signifies that she is a single woman. The color of the bow was an indicator of religion, with Protestants favoring black over the bright color choices of Catholics.

A Cossack man, circa 1906-1914. At this time Cossack soldiers were required to provide their own arms, horses, and uniforms at their own expense. His papakha lamb-wool hat and green cherkesska coat means that he was likely from the Ussuri Cossack Host. The coat had pouches to store metal powder tubes used in early firearms.

Dynamichrome: Website | Instagram

via [Buzz Feed, Design You Trust]

All images via Augustus Francis Sherman/New York Public Library/Jordan Lloyd (Dynamichrome).