Water Lily tribe

Designer Nicholas Rougeux has spent the last year combining his love for data visualization with his tech skills to lovingly restore and place 19th-century texts online. After the success of Werner's Nomenclature of Colours and the geometry tome Byrne's Euclid, Rougeux is tackling a new topic—botanical illustration.

After scouring the internet for different 19th-century botanical catalogs, Rougeux set his sights on Illustrations of the Natural Orders of Plants by Elizabeth Twining. This 1868 two-volume catalog is the second edition of a work first published in 1849 (volume 1) and 1855 (volume 2). The rare first edition can go for upward of £40,000 (about $49,000), but luckily for Rougeux, the second edition is available for consultation online at the Internet Archive (volume 1, volume 2) and the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

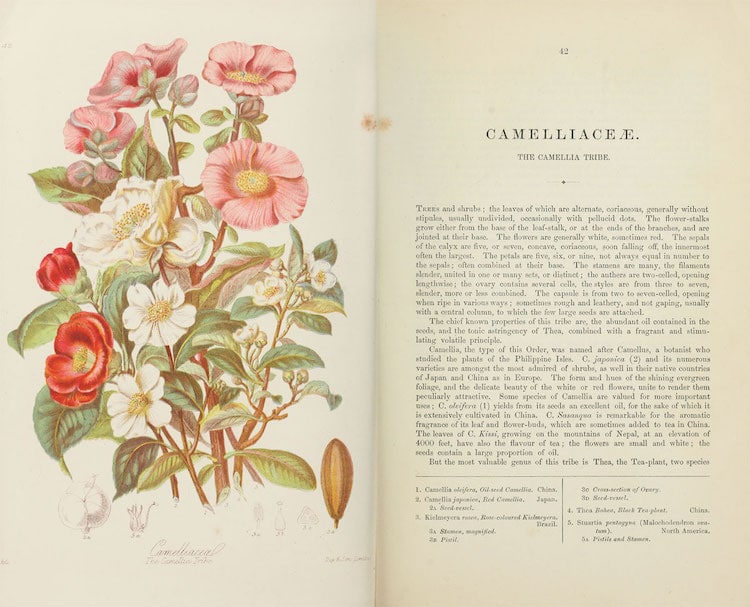

What makes Twining's work so fascinating was her decision to place plants from her native Britain alongside plants from other countries. She grouped plants into tribes based on multiple characteristics beyond reproductive organs, a technique developed by French botanist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle. This creates lush, colorful plates of bouquets next to descriptive text.

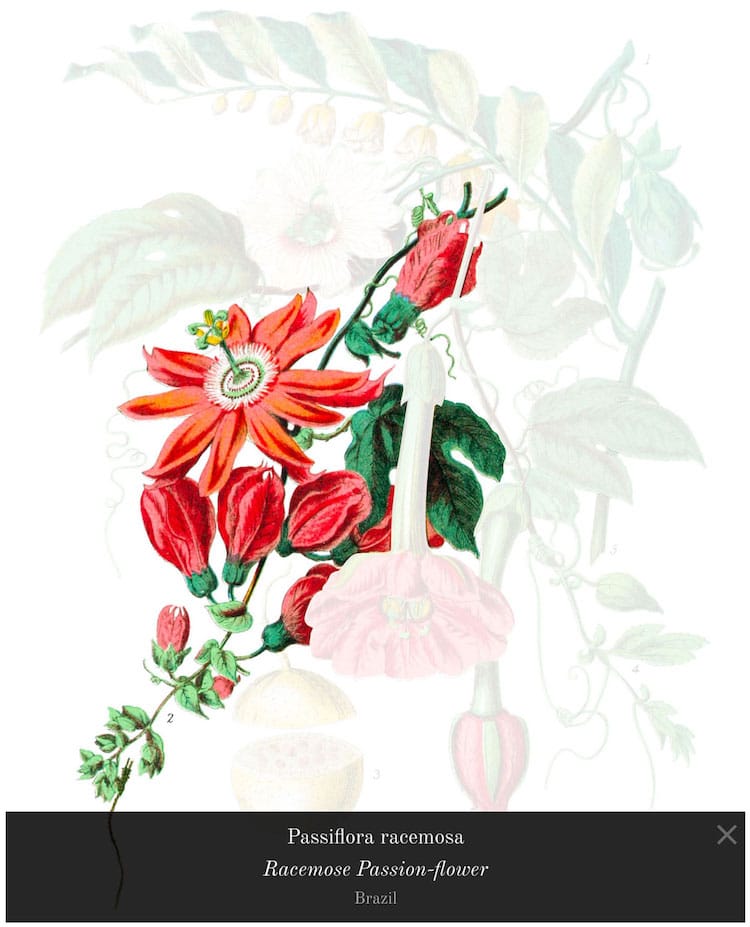

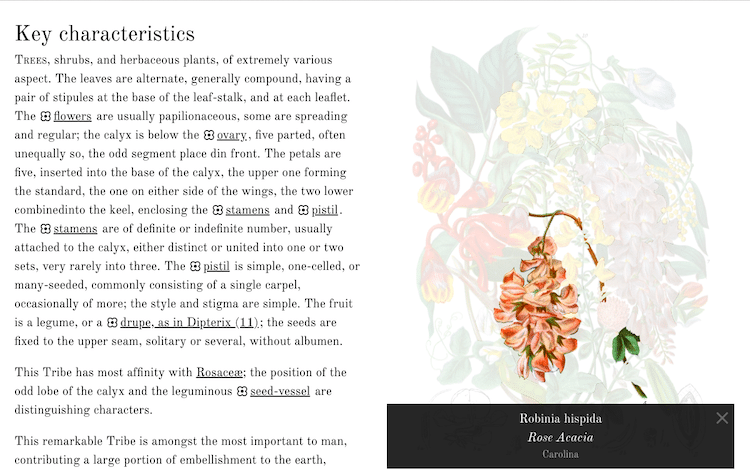

For Rougeux's online version of Illustrations of the Natural Orders of Plants, he painstakingly restored each plate, pulling out the rich detail and color of Twining's botanical illustrations. Each plate is interactive, allowing you to click and isolate single plants within the bouquet. The texts are also clickable and link from plate to plate, making it easy to jump around and explore.

As an added bonus, he's even created a “diagram of likenesses.” As Twining often writes about how plants are interrelated, this interactive diagram makes it easy to see how one tribe relates to another. Whether you love botanical illustrations and gardening or are simply fascinated by data, it's easy to get lost in the beauty of the work.

My Modern Met had a chance to speak with Rougeux about his latest project and how he went about tackling the restoration of this 19th-century botanical catalog. Read on for our exclusive interview.

Mallow before restoration (left) and after restoration (right)

This is your third project tackling a historical publication. What first got you interested in transforming these texts?

I had been using older texts for other projects for a while and always viewed them as great sources for unusual data. When I started reproducing Werner's Nomenclature of Colours, I did so with the intent of extracting the colors as data points, but while doing so, discovered that the way I had planned on representing them online was similar to the original publication.

The original publication was short, so reproducing it in its entirety seemed like a logical next step. I also have a penchant for antique book design and typography that's only been amplified while working on these projects that fuel my interest.

Scan of the Camellia tribe and description from the 1868 edition

Scan of the Rose tribe from 1868 edition

How did you first hear of Elizabeth Twining’s work and what made it a good candidate for the project?

After completing Byrne's Euclid, I began looking around for my next project and stumbled into the world of botanical illustrations. I knew next to nothing about them, but during my research, I learned of beautiful catalogs created by artists or funded by patrons of the art that had large collections of stunningly beautiful illustrations. This intrigued me because I thought bringing them online could be a fun project.

However, I wanted to be able to add my own spin to them. After doing some research, I found several catalogs but each one had their own pros and cons which I detail in my making-of blog post. Elizabeth Twining's catalog came to my attention and stood out because of her unique vignettes of plants that aren't often seen together. My own spin on it was to identify each of the intertwined plants to help others understand which ones were being described in the text.

Madder tribe

What was the most challenging part of working with these botanical illustrations?

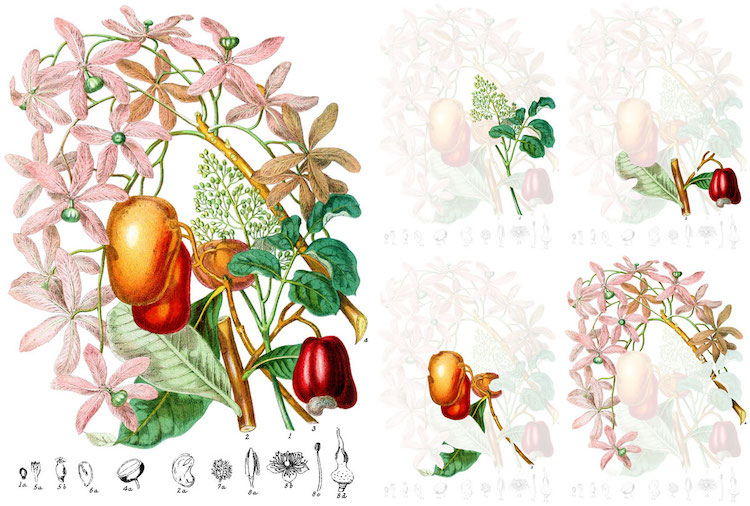

Probably identifying the plants in each illustration. While many were straightforward, several like the rose, madder, and pepper tribes proved particularly challenging because the plants were so intertwined. Making sure the right stem matched with the right blossom took many hours of careful examination, but it was also like a very fun puzzle.

Camellia before restoration (left) and after restoration (right)

What is the process for bringing each individual page to life?

Each illustration followed the same process, which I outline in more detail in the making-of blog post:

- Restore the original image: Each of the 160 illustrations was restored in Photoshop from its faded yellowed scan to a vibrant version with a clean white background. Edges were cleaned up and spotting was removed. This took anywhere from 20 minutes to 2 hours depending on the work needed.

- Trace the image: Each of the 772 plants across all the illustrations was carefully outlined in Illustrator to create hotspots so people could click on them to see just that plant separate from the others. In hindsight, this turned out to be far more time-consuming than I expected (1-4 hours each) but I still really enjoyed the process.

- Recreate the description: Each description was retyped and updated with buttons to highlight plants in the accompanying diagram along with links to other plants that were mentioned. The layout was also adjusted a bit to help with readability.

The outlining process of the Madder tribe

What’s the most time-consuming part of the process? And the most satisfying?

Tracing the plants was definitely the most time-consuming because of the many details in each illustration. There were many times where I was tracing individual hairs on a stem that measured no more than a pixel wide in the original illustration and ended up barely visible in the final result. The most satisfying was probably restoring each one in Photoshop because the process reminded me of using coloring books when I was younger.

Turpentine tribe

Prior to these projects, you weren’t necessarily an expert in subjects like botanical illustration or color mixing, etc. How does your knowledge of each field grow with the project?

I'm still far from an expert in any of those topics but that's part of the draw. With each project, I enjoy learning not only about the book itself but the topics and their history as well. There's always more to learn but I gain a greater appreciation for the topics and the artists' efforts in creating something about them. I also learn about niche interests that others have when they send me feedback.

Apple tribe

What has the reception been like? Has anything surprised you?

The reception has floored me. These projects are hobbies that I create for myself with the hopes that a few other people may find them as interesting as I did. I'm continually amazed at how many people enjoy them so much. The kind words I've received from others have been wonderful and they fuel my desire to create even more. The reception of Byrne's Euclid has really surprised me. I had been wanting to try to recreate that for some time but thought it was too niche so put it off. It ended up being one of my most popular projects.

Passiflora racemosa from the passion-flower tribe

How are these projects fulfilling for you as a designer?

I enjoy bringing new life to something that's been forgotten. Restoring these works online and creating posters lets me do that in a way that exposes others worldwide to what would have otherwise continued collecting virtual dust on a virtual shelf.

Rose Acacia highlighted within the Pea tribe

What’s next?

I've got a few projects in the works that are just as obscure as others I've done. I'm always looking for more ideas and inspiration too. Stay tuned!

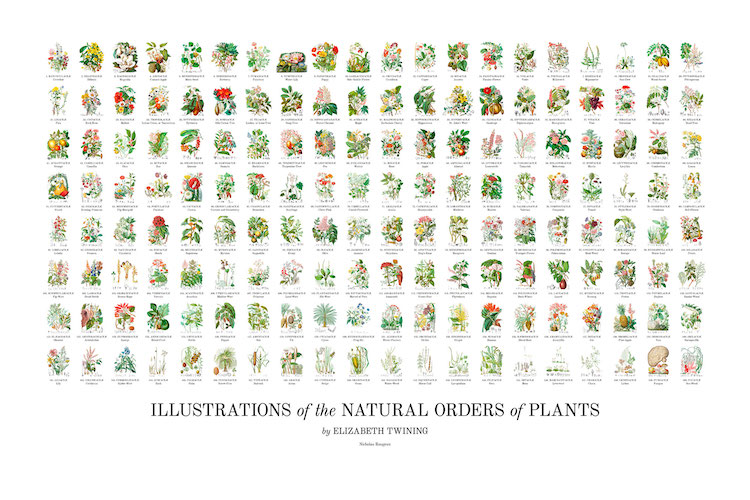

The designer also produced two beautiful posters with all of Twining's botanical illustrations.

Illustrations of the Natural Orders of Plants: Website | Posters | Blog

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Nicholas Rougeux.

Related Articles:

300-Year-Old Botanical Illustrations and the Art They Inspire Today

Biodiversity Heritage Library Puts 2 Million Botanical Illustrations Online for Free

19th Century Biologist’s Illustrations of Microbes Bring Art and Science Together

Download 130-Year-Old Watercolors of Newly Discovered Fruits of the Time