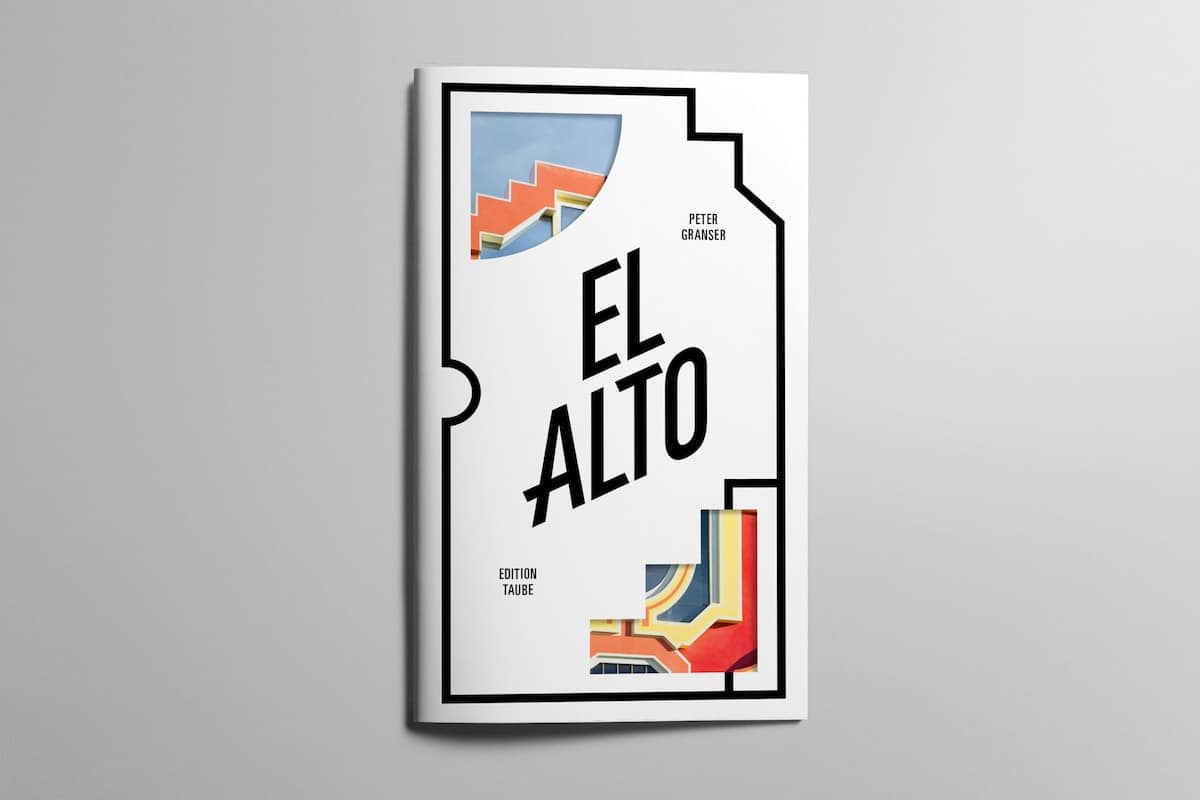

Architecture is more than simply construction, it's a creation expressing a specific culture at a particular moment in time. And nowhere is this as evident as in Bolivia, where former bricklayer turned star architect Freddy Mamani Silvestre has transformed an entire city and created what is now called New Andean Architecture. Over 24 pages, photographer Peter Granser's book El Alto, published by Edition Taube, captures the sensational creations that dot Bolivia's second largest city, demonstrating how new wealth and indigenous culture can combine for incredible results.

With more than 60 projects in a little over 15 years, Mamani's exuberant buildings are the work of someone not chained to blueprints, but tied to the heritage of his people. El Alto, in just a short time, has transformed from a slum adjacent to the country's wealthy capital of La Paz into a thriving city of about 1 million. Most of the inhabitants are Aymara, an indigenous ethnic group that makes up about 25% of Bolivia's population.

As expert traders, they have engaged in an import business with China that has led to an explosion of wealth in the plateau of El Alto, which has an average altitude of nearly 14,000 feet, making it the world's highest metropolis. Combined with the election of Aymara president Evo Morales and his work to pass a new constitution in 2009 that gave Bolivia's 36 recognized indigenous communities comprehensive rights, Mamani's architecture is a visual expression of this banner moment for the Aymara people.

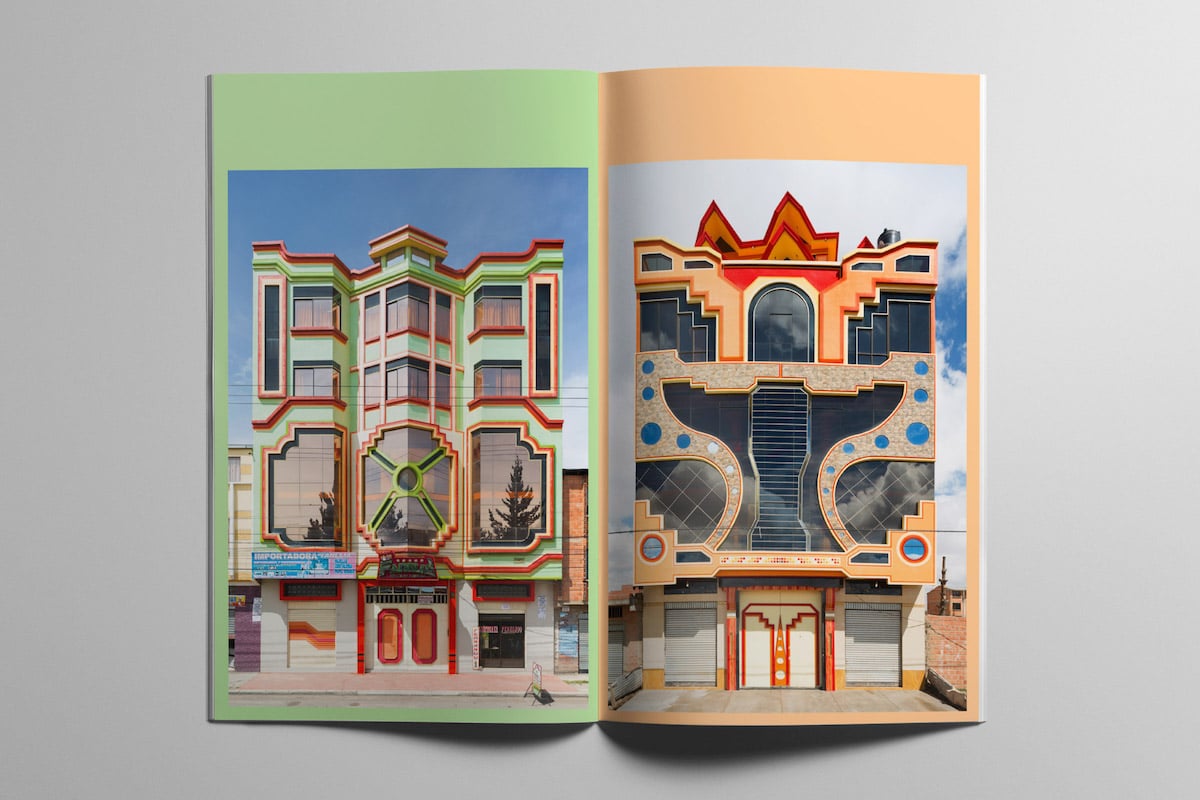

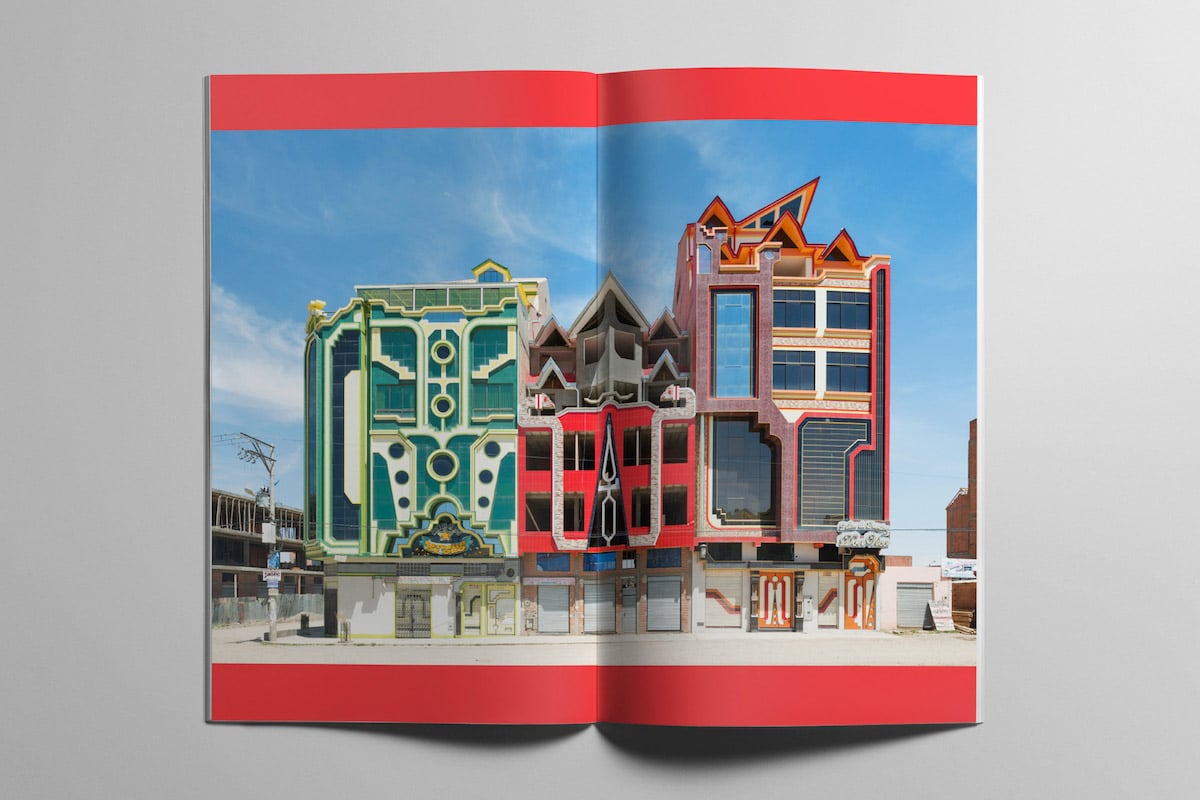

By focusing in tightly on the architecture, Granser highlights the color and form that make Mamani's work unique. Though some critics may call his work kitsch or worse (“spaceship architecture”), his two-story dance halls are filled each weekend. Beyond that, the culturally rich and vibrant buildings are an expression of the Aymara people's advancement, both socially and economically. By placing the architecture at the forefront, thereby obscuring the mountainous background, Granser's photographs also allow us to take in the intricate patterns of Mamani Silvestre's work, which draws influence from indigenous textiles.

“With my architecture I want the world to know that Bolivia has its own identity,” Mamani told the BBC in 2014. “There have always been rich Aymaras, the problem was they didn’t identify with it. Now, with this architecture, they come to the fore saying, ‘We are Bolivians, we are Aymara and we can show off our Indigenous Bolivians' new confidence and identity.'”

Since 2005, Freddy Mamani has transformed the Bolivian city of El Alto with his extravagant New Andean Architecture.

Photographer Peter Granser hones in on the color and symmetry of this new Bolivian architecture in his book El Alto.