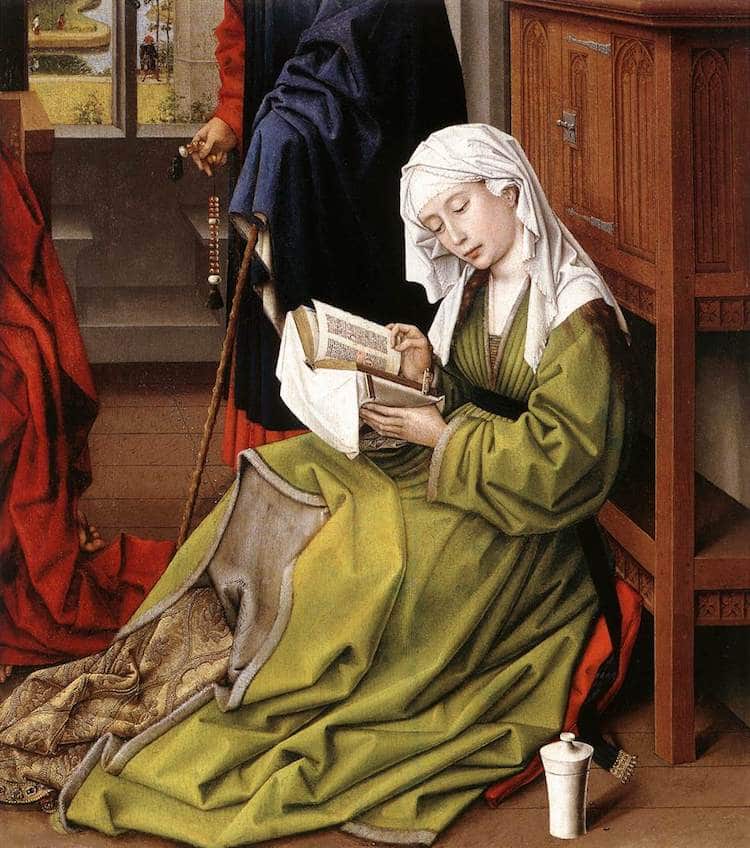

Rogier van der Weyden, “The Magdalene Reading,” 1445 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Books hold a special place in history. Existing since ancient times, their contents can give us a glimpse into the past, whether they're chronicling current events, documenting historical figures, or simply telling stories. It is not just what is found in the pages of books, however, that can teach us about history. In fact, taking a closer look at the objects themselves can be equally enlightening.

Here, we explore the history of the book. As we leaf through its antiquated beginnings, its more modern chapters, and everything in between, you're bound to gain a new appreciation for this age-old object.

Flip through a fascinating history of the book.

Papyrus Scrolls

Sculpture of Egyptian Scribe, between 1295 and 1069 BCE (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

While scrolls undoubtedly enhanced ancient methods of documentation, their vertical orientation and need to be unfurled made them difficult to handle. Centuries later, however, Romans would rectify these issues with a new prototype.

Roman Codices

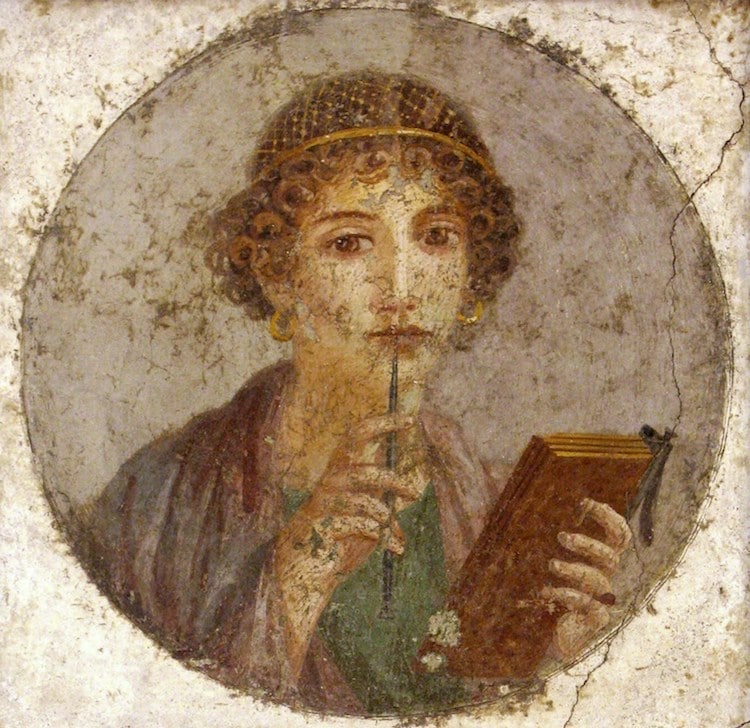

Woman holding wax tablets in the form of the codex, Wall painting from Pompeii, before 79 CE (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Today, these adaptations are credited as the earliest books.

Medieval Manuscripts

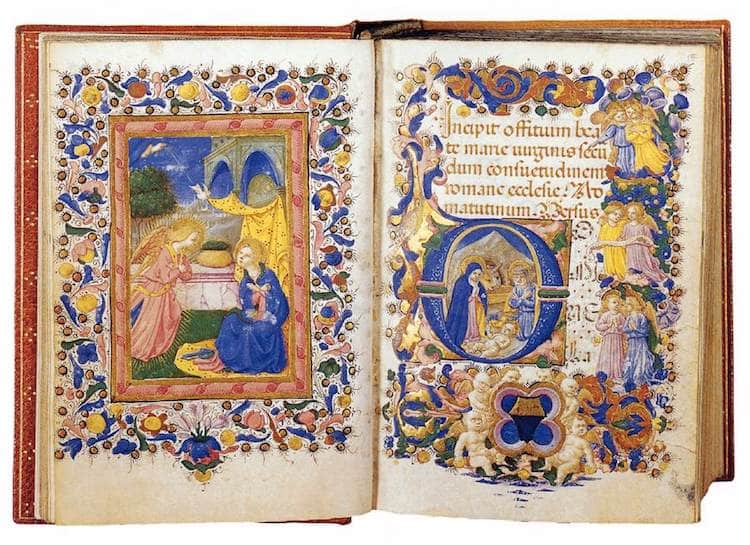

Zanobi Strozzi, “Book of Hours for the Use of Rome,” ca. 1445 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

These ornately decorated works were made entirely by hand, setting them apart from the increasingly popular printed books of the period.

Woodblock-Printed Books

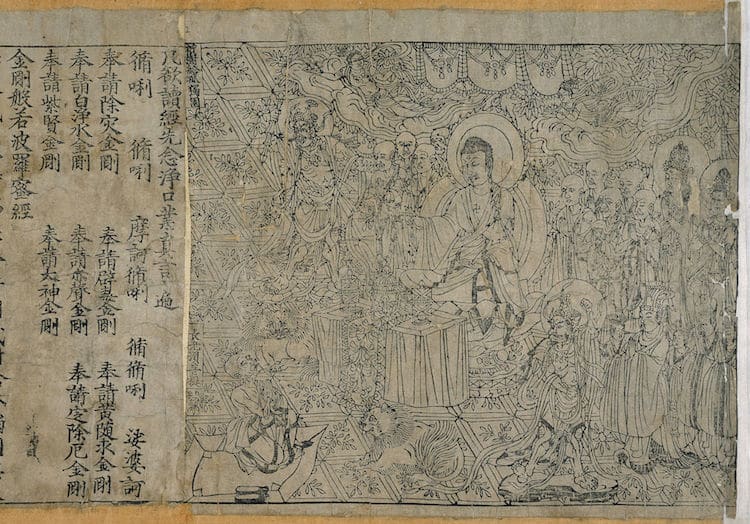

Diamond Sutra, 868 CE (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

“Essentially a picture book,” the Library of Congress explains, block-books featured “a single woodcut page in which design and text were carved, inked, and then pressed against paper, leaving an impression of image and words.” True to this “picture book” comparison, block-books typically comprise fewer than 50 leaves and feature hand-colored images.

Mass Produced Books

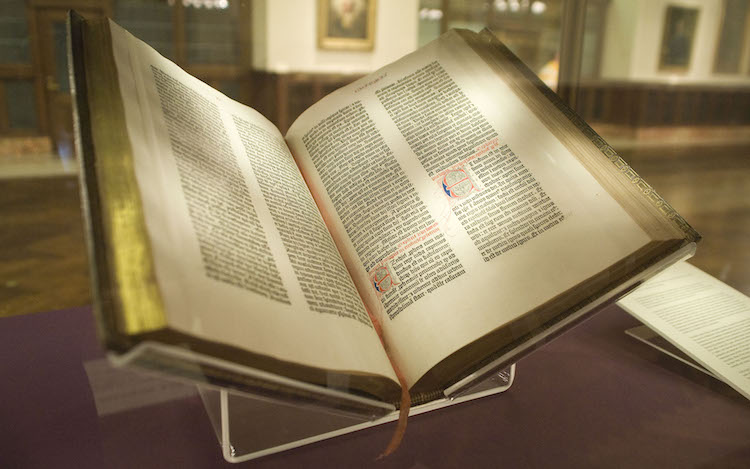

The Gutenberg Bible, ca. 1445 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

The impact of Gutenberg's printing press was particularly evident during the Renaissance, as its ability to mass produce books allowed enlightened Italian ideals to spread across the continent.

Glued Books

Photo: Stock Photos from urbanbuzz/Shutterstock

In addition to increasingly efficient methods of mass production, the printing press facilitated another bookmaking milestone: modern binding.

Until Gutenberg's invention, books' folios were meticulously fastened together using wood, metal, and thread. Following the emergence of the printing press—and the consequent commercialization of books—the bookmaking industry adapted its approach, promoting less expensive materials like cloth and glue, which became the binding medium of choice in the 20th century.

E-books

Photo: Stock Photos from ImYanis/Shutterstock

Over the last few years, the electronic book has emerged as a major contender for modern reading. While this digital iteration of the traditional book may feel completely contemporary, the concept itself is nearly a century old.

In 1930, American writer Bob Brown predicted the eventual emergence of the e-book after viewing his first film with sound. He described “a simple reading machine” that was portable and adaptable—not unlike the tablets and e-readers that would appear less than 70 years later. Brown's premonition, however, wasn't entirely accurate; he noted that, with such a gadget, he could “read hundred-thousand-word novels in 10 minutes.” While this may not be possible with today's technology, there's no telling what's next in the never-ending story of the book!

Related Articles:

You Can Download Thousands of Coloring Book Pages From Museum Collections

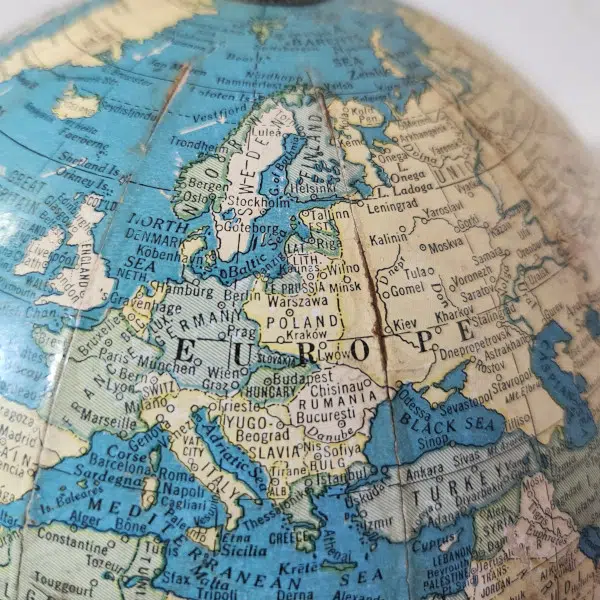

Who Is Abraham Ortelius? Learn More About the Inventor of the World’s First Atlas

20 Creative Gifts for Writers That Are Way Better Than an Ordinary Notebook and Pen