Blackwater photography freezes small aquatic animals in time (in this case, a Penaeid shrimp) so the viewer can focus on studying the details of something they have never seen before.

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

Marine biologist and photographer Jeff Milisen loves exploring the unknown. From his home in Kona, Hawaii to the waters of Papua New Guinea, he leaves no underwater territory unturned. Milisen is a pioneer of blackwater photography and is fueled by the desire to document the vast array of microscopic plankton and sea creatures that inhabit our oceans.

Blackwater photography is done during a deepwater night dive over the open ocean. Lights are then used to attract ocean, or pelagic, creatures that are photographed in their natural environment. Requiring the photographer to compose and shoot imagery while drifting in the deep sea, it's an extremely challenging craft. However, the payoff is big. Not only do photographers often come away with attractive images, but they are also helping contribute to the scientific community.

More and more frequently, blackwater photographers like Milisen are able to photograph species that have rarely—if ever—been seen. And, they are able to photograph these animals fully intact. This is important for researchers, who often receive samples after the plankton have been emptied out of nets. And more often than not, their condition is subpar.

Milisen, who also contributes to the scientific community, is bringing even more awareness to the richness of ocean life in Hawaii. After over a decade of specializing in blackwater photography, he recently published his first book titled A Field Guide to Blackwater Diving in Hawaii. With photos of over 300 pelagic animals, complete with descriptions, the book is sure to become a touchstone for both new and experienced divers.

We had the chance to chat with Milisen about what attracted him to life underwater, the challenges he faces during blackwater shoots, and where he's hoping to go next. Read on for My Modern Met's exclusive interview.

Paralarval octopus (Macrotritopus sp)

What fascinates you about the underwater world?

Underappreciated animals fuel my curiosity and my curiosity drives my need to explore. I was the creepy snake kid growing up. My room had aquariums of snakes lining one wall. Every few weeks, my parents would find one of my escaped pets crawling wild across the floor.

In high school, I even ran a small-scale tag-and-release population study on the black racers and black rat snakes at an old farm across the street from my house in Connecticut. I would skip school to catch turtles or go fishing. I’ve always been fascinated by animals, which is why scuba diving was a logical next step. Underwater, life is so much more abundant! It didn’t take long for that curiosity to transfer to fish, corals, and plankton.

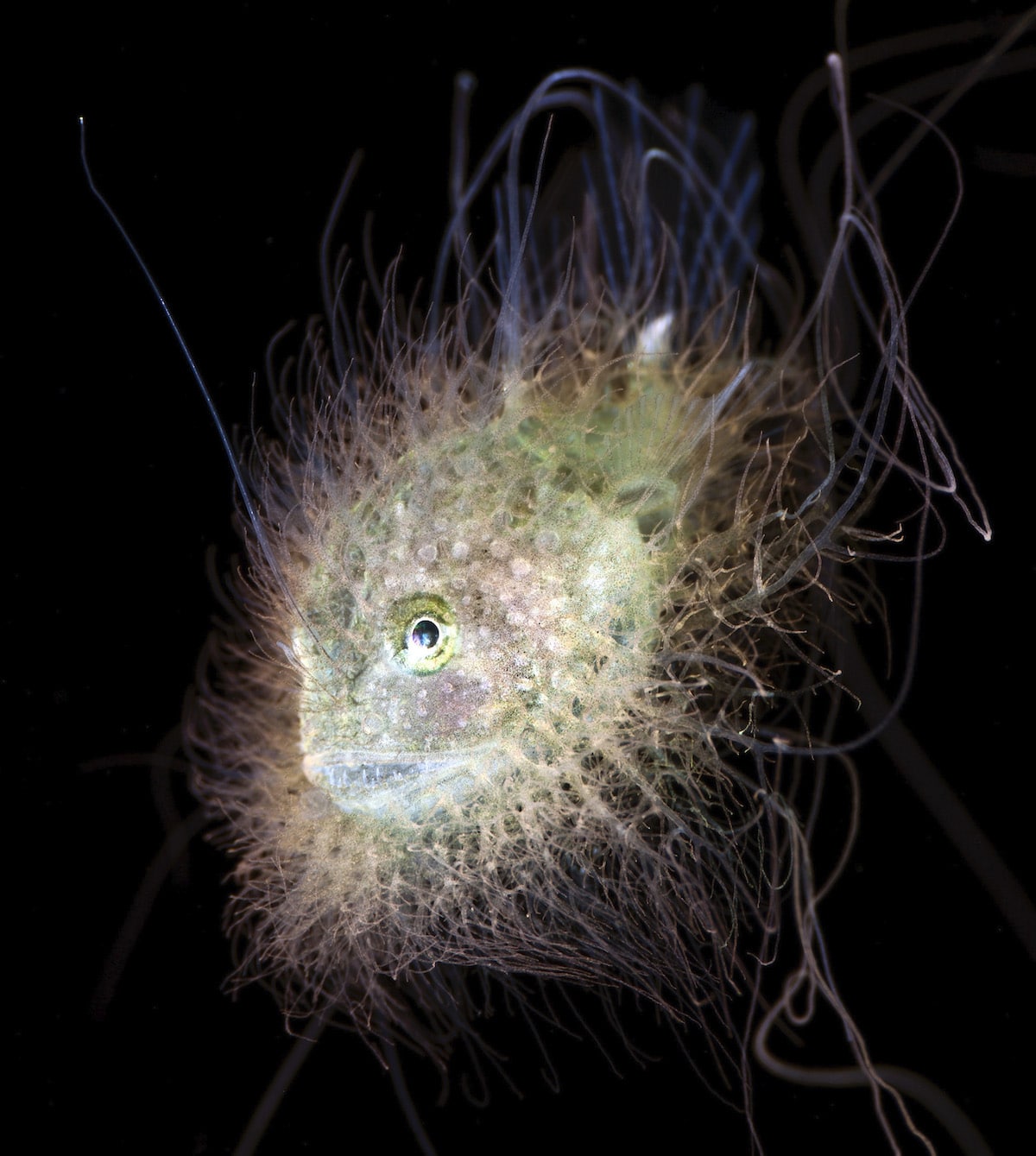

This is the first image of a hairy goosefish (Lophiodes fimbriatus) from Hawaii.

What first attracted you to blackwater photography?

A lot of blackwater photographers today hyperfocus on nailing a beautiful shot of a common animal. They often try to get the “best” photo of a few target species that have already been shot to death. There is no denying that they produce incredible photographs, but that’s not why I am here. You don’t have to be the best, you just have to be the first.

When you study a habitat, you start to recognize when something is really unusual. My favorite shots feature animals and behaviors that were never on anyone’s target species list because I never imagined I might one day see something that incredible. The feeling of photographing an animal where you know something is out of place is unforgettable because the excitement doesn’t end after I've snapped the shot or run it through post-processing. That is only the beginning.

My image of the hairy goosefish (Lophiodes fimbriatus) is a great example. I knew it was weird because I had never seen anything like it. I started by looking through the available literature for anglerfish in Hawaii. When that didn't work, I sent the images to Dave Johnson at the Smithsonian who knows far more about larval fishes than I do. And when he didn’t know, he sent it to an army of ichthyologists including Ted Pietsch, who specifically studies anglerfishes. Ted made the final determination that it was a species that had only been seen three to four times, and this was the first specimen from Hawaii! This pattern of discovery happens a lot. In the last four weeks, for example, I have seen three species of squid that I have never seen before.

The larval fishes we see come from every corner of the nearby ocean. Most fish larvae develop at the surface where food is abundant, and far from the adult habitat for this cusk eel that lies thousands of feet beneath the water surface.

Squids serve as a major forage base for just about any animal that can consume one, including other squids! In this image, two squids fight over a third, unlucky friend in the middle.

What sort of research do you carry out going into one of these shoots?

Blackwater dives are highly unpredictable. If you visit the same spot two nights in a row, the seahorse that you saw the previous night isn’t going to still be there. It will have drifted away with the current like everything else. I gain my edge by studying predictors of pelagic biodiversity. Where are the most individuals of the most species going to be on a particular night? This requires looking at dive data quantitatively and using it to answer specific questions.

My first peer-reviewed paper was born from that very question. I spent five minutes out of every 15 underwater, counting the numbers of individuals of each species around me. After I had a hundred or so data dives, I had a solid dataset to work with. From there, it was just a matter of statistically asking how factors like moon phase, or ocean depth, or time of year affected the life that we were seeing.

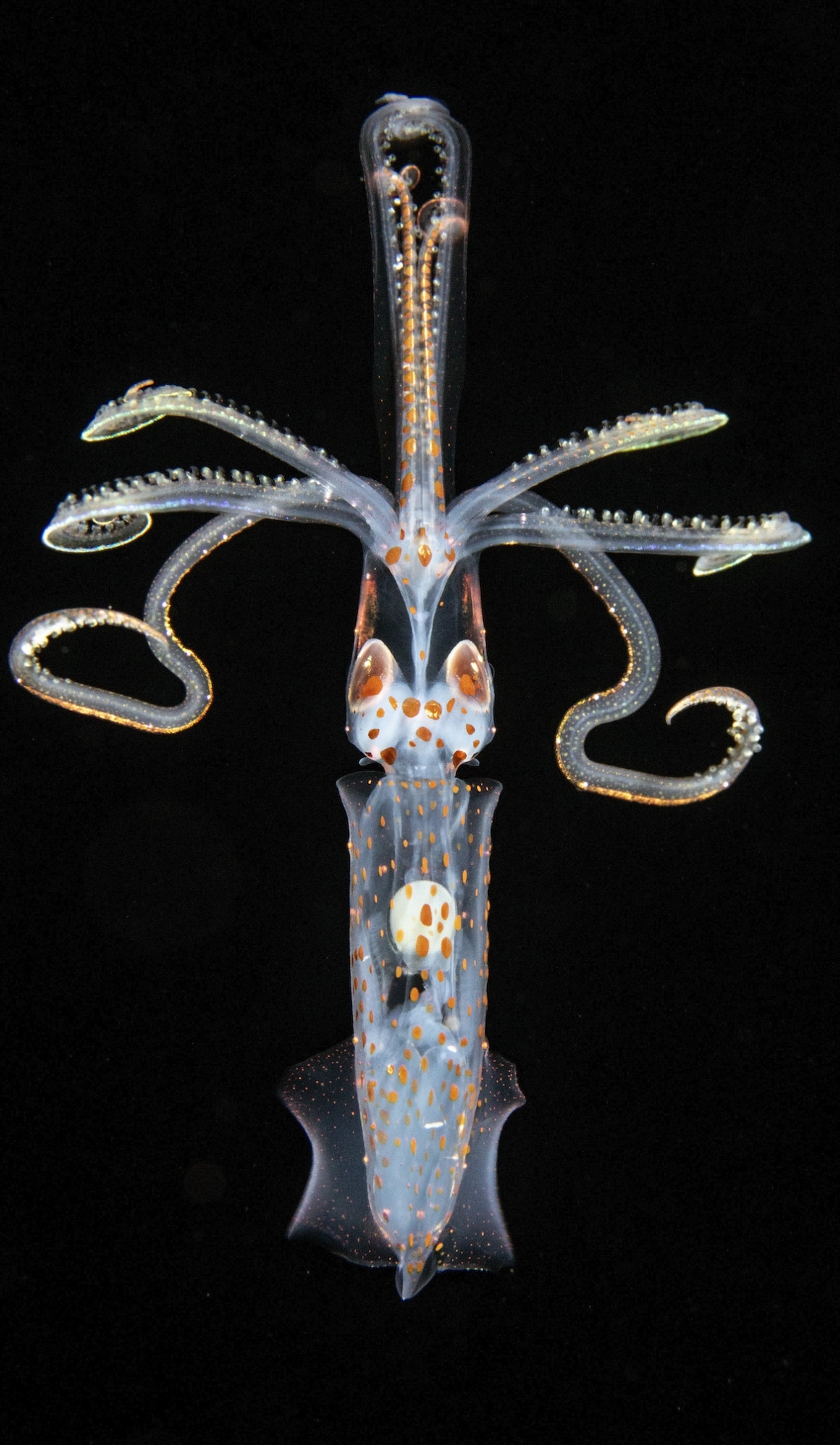

Young sharp-eared enope squids have incredible control over their tentacles so much so that they are capable of a wonderful variety of expressive poses.

As a marine biologist, can you speak about how this type of photography is also helping the scientific world?

There are a few ways that we help. Initially, I showed a photo at a conference of a fish swimming inside of a salp. A pelagic biologist in the audience approached me afterward. The way that we have traditionally studied the ocean is through various kinds of nets and plankton counters. When plankton comes up in a net, it is all mixed up. When this researcher had previously found fish inside salps, he had assumed that it was just an artifact of that mixing process that happens in the nets. So by showing him a new behavior, my photo was a game-changer for a guy that had spent his whole life studying the pelagic ocean. A lot of work has gone into bluewater diving to study behaviors.

The other way that blackwater photos help is to understand how these animals really look. Again, researchers only have specimens that have been beaten up by collection nets and then preserved in alcohol, and the results aren’t pretty. Fins are often broken, the color is washed out, the body posture is far different than what we see, and filaments are almost never attached.

They have developed methods to make the most of these beaten animals—mainly ways of counting hard body parts like vertebrae, fin rays, or fin spines. This is called “meristics” or characteristics that are counted. I recently participated in a study that looked at the in-situ photos of animals that were then collected and preserved. Then Dave Johnson at the Smithsonian ran meristics and Ai Nonaka ran DNA. Then the results of all methods were compared, and the results were surprising, to say the least.

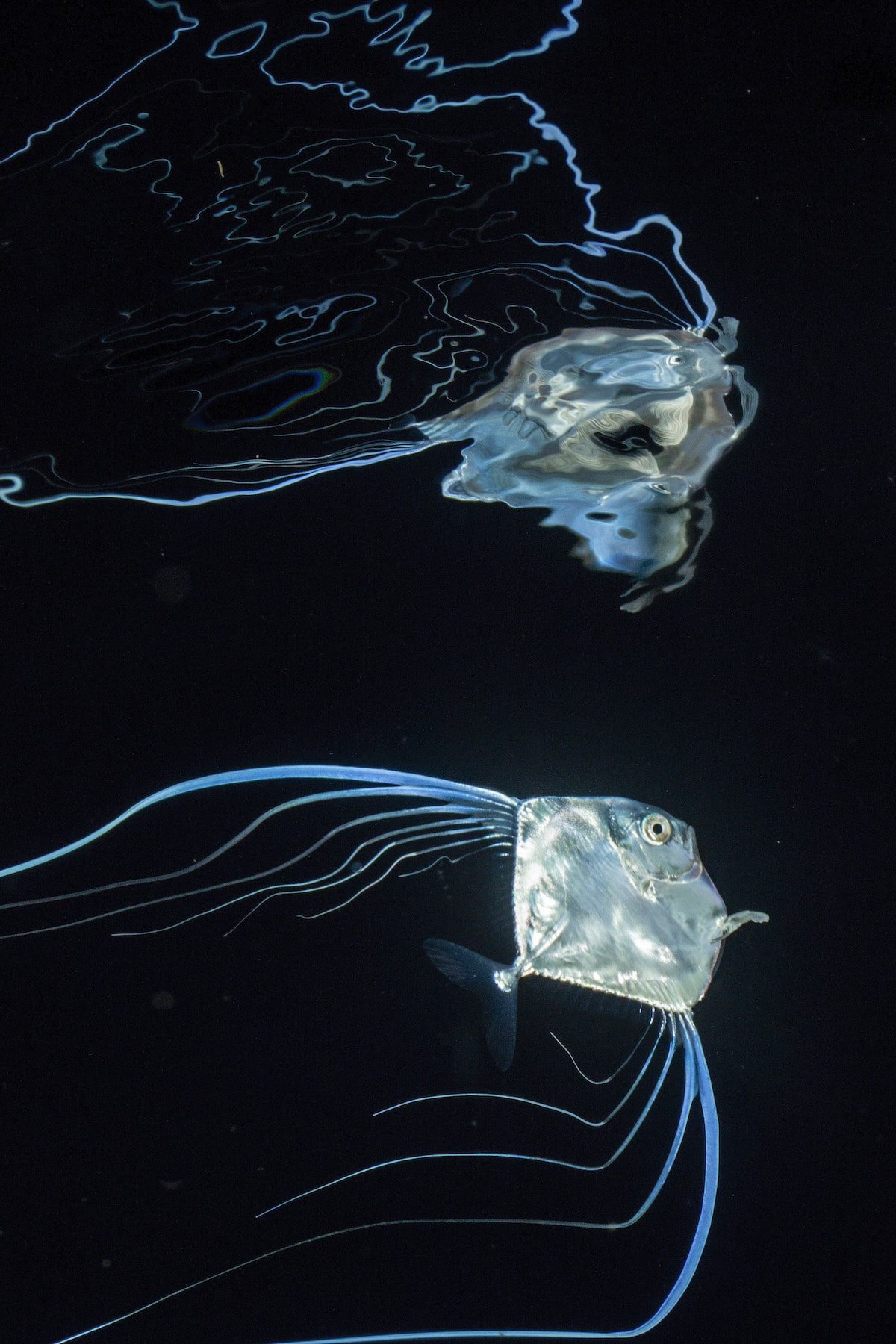

Threadfin jack (Alectis ciliaris). Even though we are drifting over 6000 feet of water, the majority of open-ocean life lives in the top few feet of the surface.

What's the most challenging aspect of blackwater photography?

There are really two: buoyancy and lighting.

As humans, we spend all of our lives navigating essentially a two-dimensional world. We have evolved to associate and orient with substrates. Rarely do we have the chance to travel up or down significantly. Even when we scuba dive, we are most frequently diving over an area with some sort of bottom. When I do a blackwater dive, the bottom is 6,000 feet below. You have to retrain yourself to orient toward something else, be it the stuff in the water (called marine snow), your dive computer, or the ocean surface. And then you have to train your eyes to focus on very small things that are also adrift. Because of the size difference, the water movement acts on your body very differently than it does on small objects, so following them on the path from your eyes, to the viewfinder, to captured on the photosensor is very challenging.

Helping in this quest is our lighting. Most people think that we are looking at bioluminescence, but that isn’t accurate at all. Bioluminescence is very, very dim. If I didn’t carry lights underwater with me, it would be a very black dive indeed. The lights don’t only help us find things, though; they also produce the contrast that allows our cameras to focus on the animals. Bright lighting is key to successful blackwater photography.

Box jellies are notorious in the south Pacific for their often deadly sting. This lobster young is not only immune, but it will use the jelly’s sting for protection, all while having its next meal on the go.

I know there is a nice community of blackwater photographers. Why do you think this type of photography, in particular, inspires such community?

The majority of the blackwater photo community is in it to produce pretty photos. The contrast between chromatophores or unusual anatomical features against a clean, aesthetic black background is a natural combination. Our eyes are naturally drawn toward the lightest part of a photo, which is why blown-out highlights are so distracting. The black water eliminates any distracting backgrounds. Of course, blackwater is all about alien subjects, so this is a wonderful way to set the subject in an environment where it stands out.

The cookiecutter shark (Isistius brasiliensis) is one of the world’s smallest shark species.

What's your favorite blackwater photo and why?

My favorite photo has to be my cookiecutter shark. It is colored a drab orange, and the compositions aren’t mind-blowing, but the subject is incredible! They are one of the world’s smallest species of sharks. They make a living using their unique dentition to scoop golfball-sized chunks of flesh from the sides of unsuspecting whales, sharks, dolphins, and gamefish. And in 2008 when I saw one—my first blackwater—only a tiny handful of people had ever seen one alive!

Wanting a photo of a cookiecutter shark was the initial driving force that started me down the blackwater path. I worked my ass off for over a decade to find one that was amenable to photography. Over that time, I slowly came to the realization that the ocean is full of animals just as fascinating and as rare as cookiecutters.

The night that I finally photographed a cookiecutter was January 1. It was the end of the dive and I was at 500 psi at my safety stop when my wife pointed at something in the distance and made the sign for “shark.” I took off and easily caught up with it. We swam together for probably five minutes and I shot 14 photographs of it before deciding that I had to go. I looked up to find the boat and it was just a distant glow. I looked at my depth and I was at 80 feet. Then I looked at my available air and I had less than 200 psi. This shark was nearly the siren song that dragged me down to the deep infinity beyond! It was also the final cutoff where I was done collecting images and decided it was time to finish writing my book. A Field Guide to Blackwater Diving in Hawaii came out in November 2020.

Larval scalloped ribbonfish (Zu cristatus)

Fish often associate with jellies for protection. In this case, a young jack hides in the bell of a larger jelly. While it looks trapped, it is free to come and go as it pleases.

Where's one place that you'd love to go for a shoot and why?

I am drawn to the remote areas of the world. Some of the best blackwaters I’ve done were in Papua New Guinea, where plastic pollution isn’t a thing because any plastic that has reached the area is cherished by the locals. The sea life was incredible just from shore, but then if you go offshore just a little way, you can dive over the tops of underwater mountains called seamounts!

I am fascinated by seamounts, and the ocean is generously sprinkled with so many; a lot of seamounts don’t even have names. I’d also love to go even wilder and focus on areas that have the perfect mix of oceanographic conditions where life just explodes. Sure, the coral triangle is in there, but I’d imagine that somewhere like the ocean around the northern Line Islands. There is something about that area that causes life to compound on itself, and I would hope that would translate into the pelagic realm as well.

Gempylus serpens and Sthenoteuthis-Snake mackerels are large, fast predatory fish that migrate vertically every night. Because of their deepwater habitat, they are rarely seen. The timing to catch this fish consuming a squid was just dumb luck.

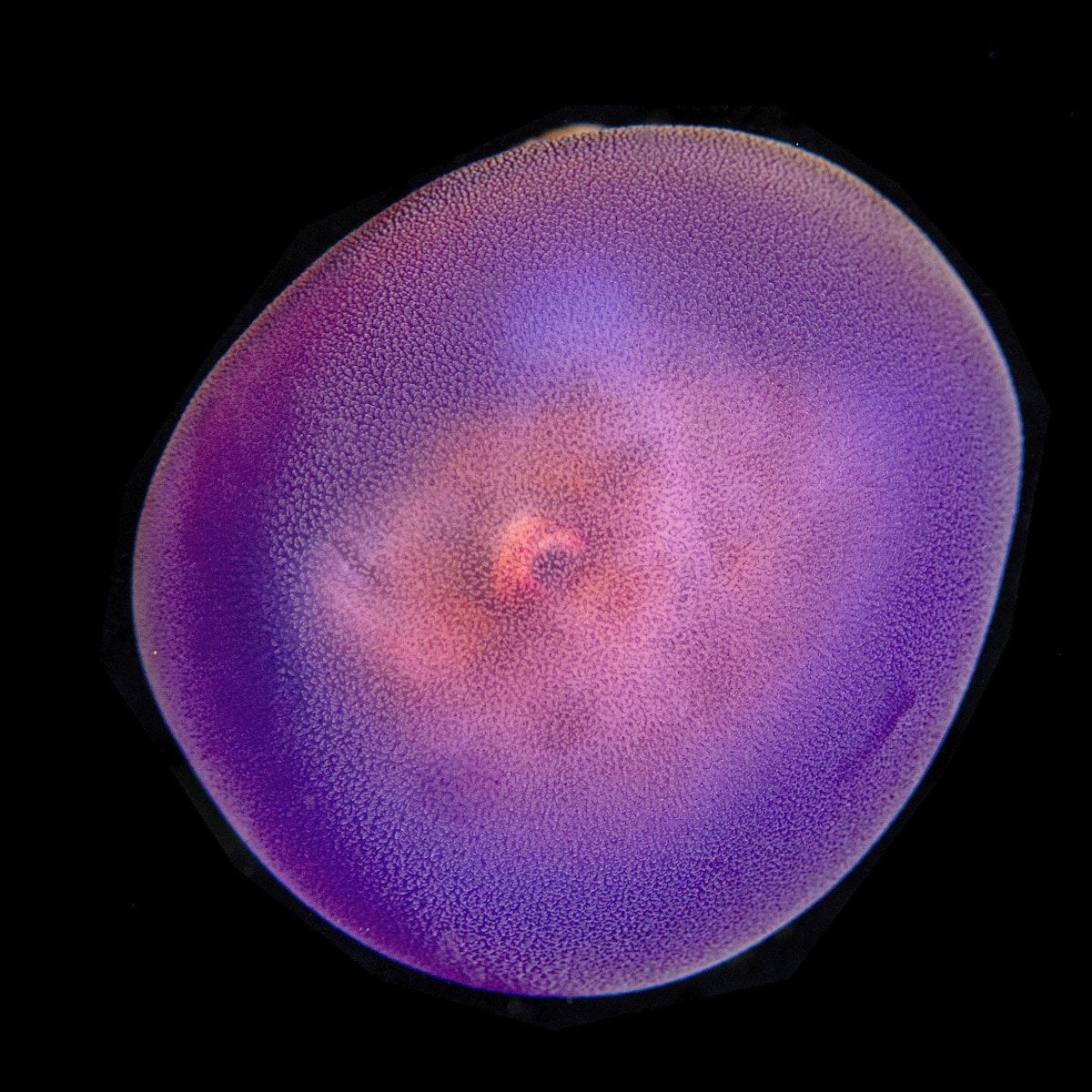

The central shell of a veliger will eventually grow to be the center, or protoconch, of a snail shell with those elaborate wings becoming the snail feet.

What do you hope that people take away from your work?

My work is just a small taste of the amazing weirdness that drifts past our shores every night! It is easy to get people to pay attention to coral reefs and dolphins. It isn’t often that we can inspire people to care about plankton, but it is so important! Plankton drives the populations of reef fish that call coral reefs home, and it feeds those dolphins that people care about. Plankton is the dominant community of over 70% of our earth’s surface. It deserves some love, too.

Watching unique interactions among the plankton is one of the more fascinating aspects of blackwater. Often, as in the case of this octopus and seahorse, the nature of the relationship is completely unknown.

Jeffrey Milisen: Website | Instagram | Twitter

My Modern Met granted permission to feature photos by Jeffrey Milisen.

Related Articles:

Captivating Portraits of Luminous Underwater Creatures

Dazzling Blue ‘Sea Sparkles’ Emit a Glittering Glow on the Shores of Tasmania

Underwater Photographer Spends 20 Years Capturing Photos of Microscopic Plankton

Rare Octopus With Transparent Head Caught by Blackwater Photographer [Interview]