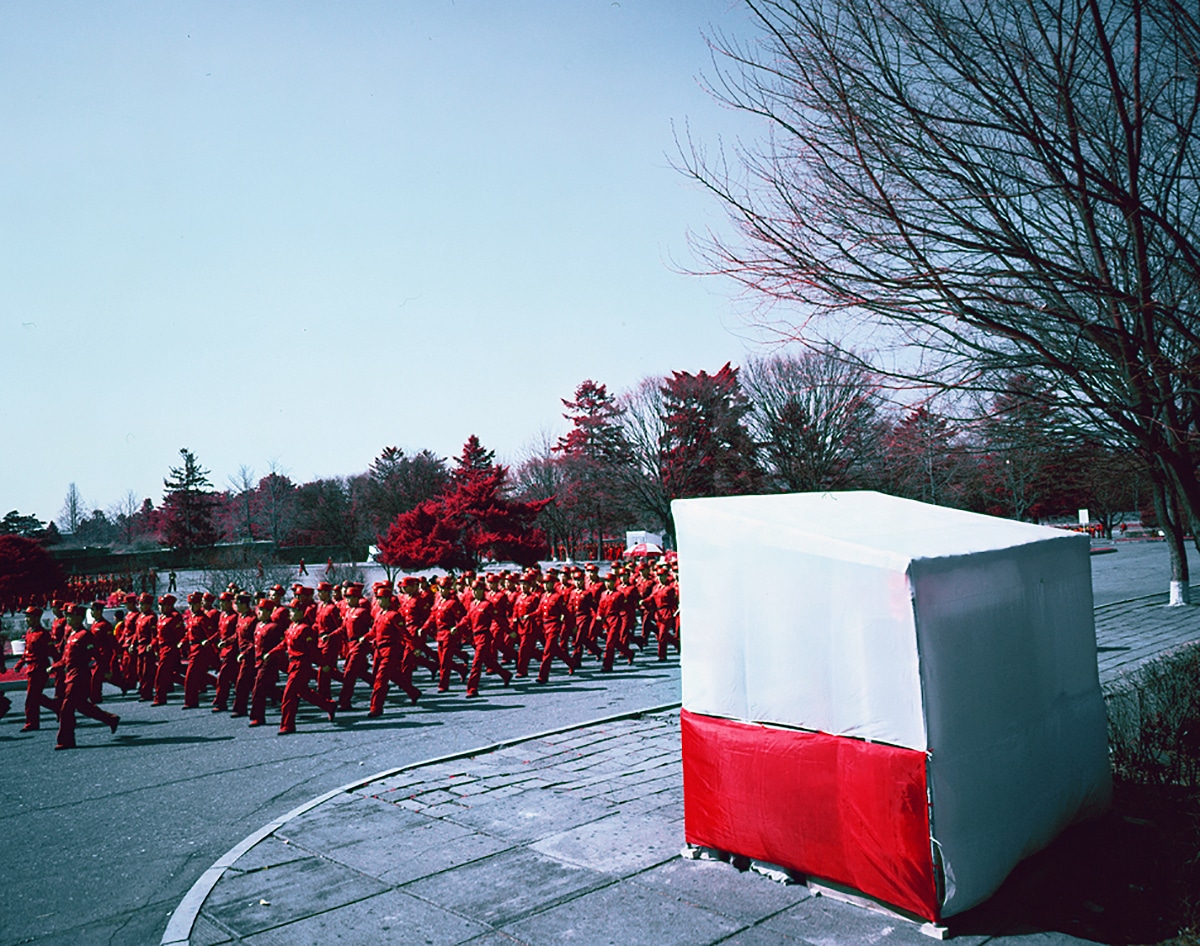

Army officers walk up a hill leading to the Revolutionary Martyrs' Cemetery in Pyongyang, North Korea. The Korean People's Army was established on 8 February 1948, and is the “revolutionary armed wing” of the Worker's Party. North Korea's “Songun Chongch’i” or military-first policy was adopted by the country's first leader Kim Jong-il. Songun's prioritizes the Korean People's Army in state affairs and resources allocation.

When Karim Sahai recently traveled to North Korea, he not only captured his journey using traditional digital photography, but gave himself an added challenge. Bringing along rolls of Kodak Aerochrome film, he also took some incredible infrared photos that show the country in a whole new light.

In addition to his photography, Sahai is a visual effects supervisor who has worked with acclaimed directors like Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson, and this creativity certainly came in handy as he created the infrared photo series. Kodak Aerochome became widely available in the 1960s and was used in the 1940s for aerial surveillance. The infrared film is known for its ability to show foliage in lush magenta and red hues and intense blue sky saturation, and the resulting photographs are surreal.

While the film has long since been discontinued, Sahai used his stash to give an artistic, timeless look at North Korea. In images that seem like vintage postcards, he takes us from glimpses of the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea to a look at the importance of women as mothers in North Korean society.

Sahai walks us through his journey in North Korea as he shares these previously unpublished images for the first time. Read on for our exclusive interview.

In juche, the ideology conceived by Kim Il-Sung, North Korea’s first leader, motherhood is defined as a selfless role for the benefit of the nation. A mother's role is to help uphold the purity and autonomy of the country.

In North Korea, the International Women’s Day is a public holiday with various events held across the country. Women are encouraged to fight for a sparkling future and to follow Party orders. Several years ago, the daily newspaper urged women to give “unconditional trust and support to the Party; if we are with the Great Leader, happiness, sorrow, or tragedy are an honor”.

Can you share how your North Korea trip came about and how long you were there?

Because of my great love of nature and wildlife, I’ve always liked traveling to places that are remote, forbidding, and cold—places where the human impact is small. Although the wildlife in and around the DMZ [demilitarized zone] is incredible, going to North Korea wasn’t about photographing animals in the wild. Although I knew it wouldn’t be possible to see absolutely everything I wanted over there, going to North Korea was primarily to satisfy my curiosity. Despite what was depicted in the news, on both sides, I wanted to experience things first hand. My last trip lasted just about 2 weeks. It was a memorable adventure in a place few get to visit.

Near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) – a no-man's-land buffer zone separating the Korean Peninsula along the 38th parallel – are the North Korean town of Kijong-dong and the village of Panmunjom. Until a mutual agreement in 2004 led to the end of the practice, huge loudspeakers and radio towers located on both sides blared and broadcast propaganda at each other. Today on the North Korean side, one can see fields and the world's 3rd largest flagpole hoisting a North Korean flag weighting 275Kg.

What gave you the idea to shoot with Kodak Aerochrome in addition to your other images?

To an outsider with an interest in culture, history, and pretty much everything else that is different from the way of life I’m most familiar with, a place like North Korea is a little bit like a different planet. I think it’s almost impossible to visit North Korea with a neutral mindset.

There are many things that are bound to equip you with a tinted view of things about that country: everything that happened in the Korean peninsula since 1950, the way the country is portrayed in the media, its militaristic society, its own actions at home, and on the world stage, etc… I knew that no matter what I thought, had seen and read prior to my going there, I would still go with somewhat of a filter. For this reason, I thought it appropriate to photograph some of what I saw in North Korea with an analog camera and with a film that is sensitive to the infrared and visible light wavelengths. The resulting images are striking in a way because they show the moments of everyday life that I captured in a pleasing, yet unusual, way.

A suit-wearing man takes a break on the road between Pyongyang and Wonsan. North Koreans dress conservatively most of the time and, in this highly militarized nation, army uniforms are a common sight.

How did shooting with this film challenge you—or open you up creatively?

Technically speaking, taking photos with this film is challenging for sure! The first challenge is availability and high price. I purchased a large stock of this film many years ago, just after Kodak stopped manufacturing it in 2007. Aerochrome is a film that must be stored in a freezer and its processing must be carried out by a professional lab or someone with experience.

Another challenge is the medium format film camera I chose can only take 10 pictures per roll. This is very limiting, but in a good way. I had to be deliberate with what I photographed and be very careful about the ambient light. Another limitation of this film is its narrow exposure latitude. Over and under exposure will produce poor results.

To obtain the color palette I was after, I chose to process this film as a color positive (it can be processed as a color negative too). This means finding a laboratory which can still do E6 processing. The great majority of labs that can do this well have gone out of business. The few that remain might do it every now and then, which means that the chemical bath used might not be of great quality. Or the lab might just not be in your neighborhood, which means shipping the unprocessed film and risk it being damaged by heat. Initially, I was lucky and grateful to have a great lab locally operated by very conscientious people. But film processing is costly, so I eventually set up a lab at home for processing my own film.

Processing aside, to make the most of any film, including Aerochrome, one should use a good dedicated film scanner. It’s possible to get relatively good results on consumer-grade scanners, but I feel they don’t do the film justice in terms of quality and dynamic range. The best film scanners out there are drum scanners. They are cumbersome, heavy, hard to use machines that are no longer manufactured but they produce the highest resolution and sharpest scans, with the greatest dynamic range. I’m fortunate to own a drum scanner which closes the loop of technical challenges that come with taking pictures with the Aerochrome film.

Creatively speaking, in addition to the subject, I had to take into consideration the environment and the elements in it that would bounce light in a specific way, the direction and strength of the light to produce the best infrared colors. In the end, it was a much slower process than with a digital camera or normal color film. And this forced me to try to previsualize in my mind what the result looks like. Thankfully, most of the pictures turned out the way I imagined.

A man attempts (a little late) to prevent me from taking a picture. Although photography is permitted in North Korea, the government mandated guides who accompany you throughout your stay in the country will determine what is off limits. Generally speaking, you will be prevented from photographing scenes that can portray the country negatively.

We’ve featured a lot of photographers who have visited North Korea and know that obviously, what you can photograph is heavily regulated. What did it feel like, as someone used to a certain amount of creative freedom, to shoot under such conditions?

I won’t sugar coat it. When in North Korea, it’s not really possible to take photos of absolutely everything, anywhere. One of the reasons is that as a visitor, you will only see a small fraction of the country. Also, there exists a concern on the North Korean government side that some types of pictures could be used to unfairly or negatively portray certain aspects of life in their country.

There is room for a long debate there but, as in every country, there are rules and expectations. The ones in North Korea can feel restrictive, but they are what they are and one knows what to expect before going. Given the limitations and controls in place, the creative freedom was in my own ability to capture the mood of any given scene, to tell a story with the images to the best of my ability, to combine light, colors, and composition in a hopefully pleasing way and ultimately, to also use images as a means to not only capture the weird, the unusual and the over-the-top, but to visually record things and moments that can foster engagement, things that show commonality instead of disconnection.

Military personnel gathers on Mount Taesong, close to the North Korean capital, Pyongyang. Besides its growing nuclear arsenal, the massive size of North Korea's military is arguably one of its assets. With 1.2 million active members and almost 8 million reservists, North Korea's army is one of the largest in the world.

Is there anything you wished you’d been able to photograph that you weren’t allowed to?

Well, it’s not like the government-mandated guides that accompany you almost everywhere share a list of places they’re not going to take you to. So it’s hard to say. I would have loved to spend even more time in the countryside and or to even take a Korean class in North Korea! In any case, I was surprised by the number candid moments with people in the street, facilitated by the small digital camera I had with. A great barrier-breaker!

People work in a field near the village of Panmunjom, close to the Demilitarized Zone separating the two Koreas. Although food production is markedly higher than during the North Korean famine of the late 1990s, seasonal climate variations and droughts continue to negatively affect food production and supply. Dry weather cause delayed planting which impacts crops during the growing season.

What do you hope people take away from your photographs?

Even though I really enjoyed seeing North Korea and bringing back memories from there with my pictures, I am aware that what I saw was a very small chunk of everything else that remains unseen. Whether or not my pictures facilitate this, my hope is that there is more engagement, at every level. North Korea and their people are still part of humanity, regardless of the style of government they have and ideas they believe in.

A large mosaic adorns a building near the entrance of the Museum of American War Atrocities in Sinchon (South Hwanghae province). The museum presents grim stories and artefacts from the Korean War period in Sinchon, where more than 35,000 people died between October and December 1950.

Soldiers rehearse for a general parade marking the birth of Kim Il-Sung, the leader of North Korea from its establishment in1948 until his death in 1994. He was born during the Japanese occupation of Korea. Kim Il-Sung joined the anti-Japanese resistance at the age of 14 and participated in guerrilla actions against the occupying power. As Japan's hold grew over Korea and China, Kim Il-Sung fled to Siberia. Upon Japan's surrender at the end of WWII, Kim Il-Sung returned to Korea in August 1945. One month later, the country was divided along the 38th parallel.

There are four distinct seasons in North Korea. Winters are long and cold with temperatures ranging from -20 to -40 °C. Monsoon winds bring moist air from the Pacific Ocean in the summer, making it a usually short and rainy season. In recent years, monsoon rains haven't been sufficient to fill reservoirs used in hydropower generation. This has lead to severe electricity shortages and drought. Electricity is crucial for Kim Jong Un's “byungjin” policy — simultaneously developing the country's economy and nuclear weapons.

Rural scene in spring, in North Hamgyong province.