Leonardo da Vinci, “Lady with an Ermine,” c. 1489-91. (Photo: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons .)

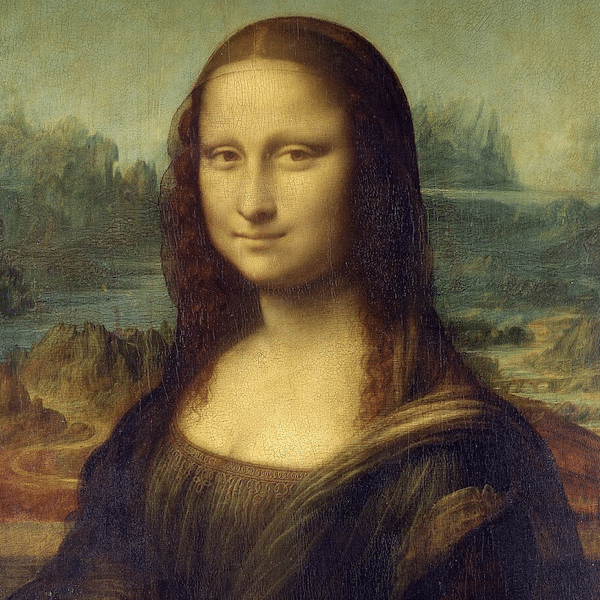

Renaissance master Leonardo da Vinci produced vast amounts of work in the fields of art and science. From his numerous notebooks filled with drawings to large biblical frescoes and oil paintings, there is a lot to explore. The commissioned portrait that preceded the beguiling Mona Lisa, for instance, is often forgotten from Da Vinci's list of masterpieces. Entitled Lady with an Ermine, this oil painting is a classic example of High Renaissance portraiture and the chiaroscuro style.

The painting depicts a young woman with plated hair holding a large, white weasel (also called an ermine) in her arms. While this painting is an excellent display of Da Vinci's interest in anatomical realism, it also uses the ermine as a symbol with meanings related to the subject of the portrait and its patron.

Here, we will explore the historical background of this Lady with an Ermine, as well as unpack the symbolism behind this unusual choice of animal.

Renaissance Portraiture

Leonardo da Vinci, “Ginevra de’ Benci,” c. 1474-78. (Photo: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.)

The Italian Renaissance is characterized by a renewed interest in classical ideals, including naturalism in art. In painting, this new approach manifested itself in realistic depictions of people. Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519) was one of the leading figures in the field of portraiture for capturing contemporary women in humanist and seemingly secular portrayals using the relatively new medium of oil paint. His most celebrated work of art, the Mona Lisa, is often regarded as the hallmark of Renaissance portraiture.

Commissioning the Lady with an Ermine

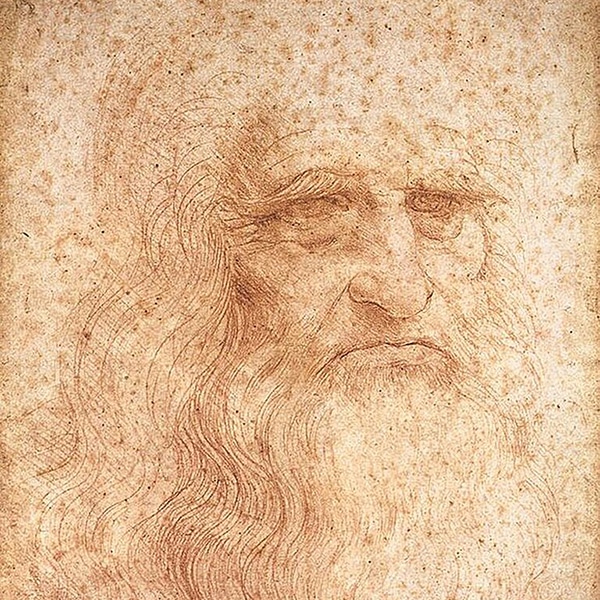

Left: Giovanni Ambrogio de Predis, Portrait of Ludovico Sforza,” c. 1452-1508. (Photo: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.) | Right: Engraving by Cosomo Colombini after Leonardo da Vinci’s self portrait, ca. 1500. (Photo: Stock Photos from Everett Collection/Shutterstock)

Da Vinci was commissioned to paint Lady with an Ermine by his patron of 10 years, Ludovico Sforza (1452 – 1508), the Duke of Milan. (He was the same person who commissioned the mural painting, The Last Supper). The subject of the portrait is Sforza's 16-year-old mistress, Cecilia Gallerani. She is depicted from the waist up in an ornate blue and red dress with full sleeves, a black beaded necklace, and a plated hairstyle. In her arms she holds a white weasel, also called an ermine.

Like all of Da Vinci's paintings, the portrait of Gallerani displays a commitment to naturalism. This is evident in the modeling of the woman's face, chest, and especially the left hand cradling the animal. It is also made in the chiaroscuro style—a technique emphasizing light and shadow to create visual depth.

The Symbolism of the Ermine

Leonardo da Vinci, “Lady with an Ermine,” c. 1489-91. (Photo: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Many observers of the painting have pointed out that the white ermine is too large to be anatomically accurate; this would be an unusual mistake for an artist and scientist like Da Vinci, who was a great admirer of wildlife. However, historians attribute this to the creature's symbolic purpose.

For one, the ermine in its white, winter coat, was regarded as a traditional symbol of purity. Da Vinci himself was fascinated by the animal, and he made several drawings of it around the same time as the portrait. One of these sketches depicts an ermine surrendering to the hunter as a representation of these virtuous ideals. By having the subject hold a white ermine, Da Vinci was referencing the woman's purity.

Leonardo da Vinci, “The Ermine Hunt,” pen and brown ink over traces of black chalk on paper, c. 1490. (Photo: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Additionally, the ermine has significance to the patron of the portrait, Ludovico Sforza, who was called the “white ermine” for his affiliation with the Order of the Ermine. So, in having the sitter hold the animal, the painting confirms their romantic relationship. There is also speculation that the ermine could be a play on the subject's surname, Gallerani, which is related to the Greek word for ermine, galê (γαλῆ).

Theft and Recovery During WWII

Photograph of the “Monuments Men” — Frank P. Albright, Everett Parker Lesley, Joe D. Espinosa — and Polish liaison officer Maj. Karol Estreicher pose with the painting upon its return to Poland in April, 1946. (Photo: Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.)

After Da Vinci's patron died, the Lady with an Ermine exchanged many hands. Eventually, in the 1880s the painting was housed in the Czartoryski's family home in Krakow, Poland. It remained there until WWII when Nazis stole it and sent it to the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin. The portrait subsequently became of interest to the Governor-General of Poland, Hans Frank. In 1946, the work of art was recuperated from Frank's Bavarian home by American troops and returned to the Czartoryski Museum in Krakow, where it remains to this day.

Related Articles:

Where to View Leonardo da Vinci’s Notebooks Online for Free

The History and Legacy of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mysterious ‘Mona Lisa’

5 Johannes Vermeer Paintings That Prove Why He’s the “Master of Light”

20 Famous Paintings From Western Art History Any Art Lover Should Know