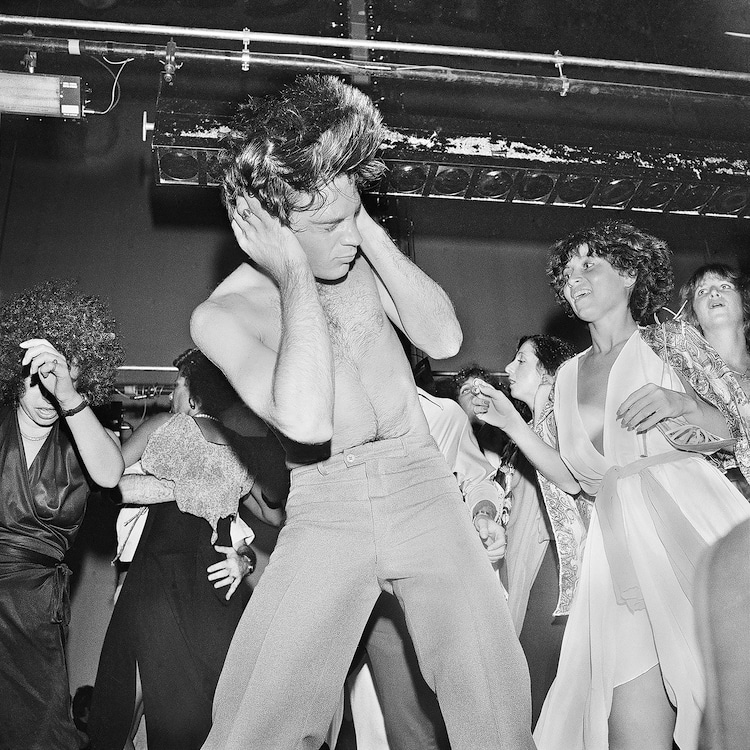

Holding Head as Hair Flies While Dancing. Studio 54, July 1977.

It's easy to feel the pulsing disco beats and red hot energy in photographer Meryl Meisler‘s collection of images. Her work weaves a tale of New York's 1970's unparalleled nightlife scene. As a young artist in her 20's, Meisler spent the 70's out on the town, camera in tow, ready to capture any click-worthy moment.

The result is a vast archive of photos that put her in a category with others who captured the spirit of NYC in the 70's and 80's. Born in the South Bronx and raised in Long Island, Meisler's body of work is only recently being discovered after her retirement as an art teacher in the New York public school system.

Since 2010, she's published two books that capture the spirit of the disco era, A Tale of Two Cities: Disco Era Bushwick and Purgatory & Paradise SASSY ’70s Suburbia & The City and is currently working on a third to complete her trilogy of 1970's New York. We had a chance to ask Meryl about life during the disco era, what Studio 54 was really like, and how Bushwick has changed since she taught there in the 1980's.

Read on for our wide-ranging interview with Meryl Meisler, a fascinating look at what it was like to both participate—and document—nightlife in 1970's New York.

Elbows at Angles. Infinity, August 1977.

What originally drew you to New York nightlife?

There I was, in my twenties in New York City, “The City That Never Sleeps.” Energy, excitement, and adventure filled the air day and night (and still does in my opinion). Why not go out and explore the nightlife? It was so varied and fascinating. Besides, as a freelancer, I didn’t have a steady job to show up to early every morning.

You were working as a freelance illustrator in the 70s, what made you decide to pick up your camera and photograph what was happening in the discos?

I started photographing as a child of 7 and studied photography for the first time as a graduate student in Art at the University of Wisconsin at Madison 1973-75. When I moved to NYC in 1975, I was—and still am—a little shy so I brought my best friend, my camera, almost everywhere I went. It helped me meet, talk to people, and “open doors” — including the discos. I danced with my camera.

People are still fascinated by the allure of Studio 54, why do you think that is?

NYC was filled with great clubs opening all the time that were over the top, but Studio 54 raised the bar higher and higher. Photographs, movies, and anecdotes give you a sense of its luxurious contemporary décor, performances, sound system, surprises, nightly changing party themes, lights, smoke, mirrors, and perhaps some magic. Throngs of people wanted and waited to dance the night away and mingle with the outrageous clientele and celebrities. Other clubs, many featured in my book A Tale of Two Cities: Disco Era Bushwick were fabulous, too.

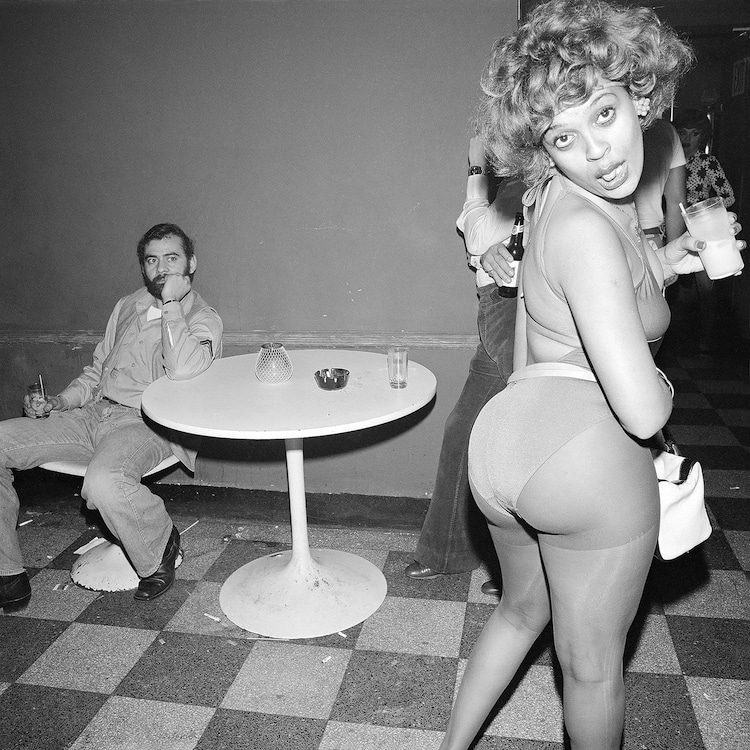

Turn Around with Drink In Hand. GG Barnum's Room, December 1978.

What was it about the energy of disco that spoke to New York? As a New Yorker, what did it mean to you?

The energy in disco paralleled the energy I felt in New York City. The sound was like a current that fed off excitement and experimentation, outsiders developing their own mainstream. Perhaps it was similar to the birth of the Blues and Jazz of previous generations and locales. Back then I didn’t realize that NYC was a birthplace of Disco, it just felt like beautiful wild gardens were sprouting in secretive spots around the city and I wanted to check them out.

What was the most shocking contrast between your suburban home and what was happening in the city?

I was born in the South Bronx and my family moved to North Massapequa, Long Island when I was two. Every house looked nearly the same on the outside within each “development”. On the inside, it was a different story — with an emphasis on detail, expression of family/cultural identity, and décor popular at the time. Every household consisted of parents and children. There was only one single parent on the block. I knew every family with kids around my age on my block and played at one point or another inside nearly every home or yard.

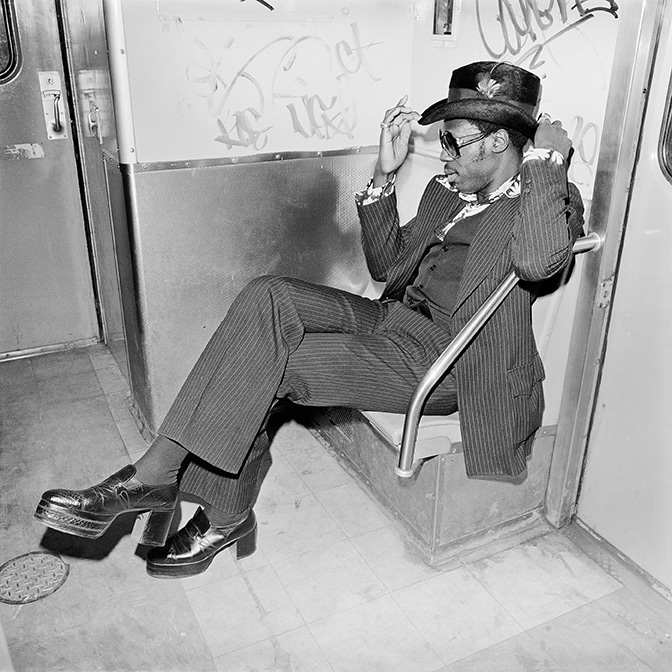

Suburbia was a place where most kids rode bikes and adults drove cars rather than walking. We rarely used public transportation other than when I was old enough to take a bus with friends to a shopping center or the beach.

Jiveguy on the Williamsburg subway. Brooklyn, March 1978.

In the city, there were so many people on one block, I couldn’t possibly know all my neighbors. There were households with and without children, people living alone, in married or unmarried couples or with roommates. Walking and public transportation were the way of travel; subways my favorite.

In Massapequa (nicknamed “Matzoh Pizza”) I’d estimate 99.9 % of the residents were Caucasian, predominately Italian, Jewish, Irish, German and Greek, first and second generation Americans. I didn’t even realize the kid with the last name Gomez in school was Hispanic. In the city, there was a marvelous mix of people from all origins, racial, religious and ethnic identities. I wasn’t the only queer person. I felt I fit right in.

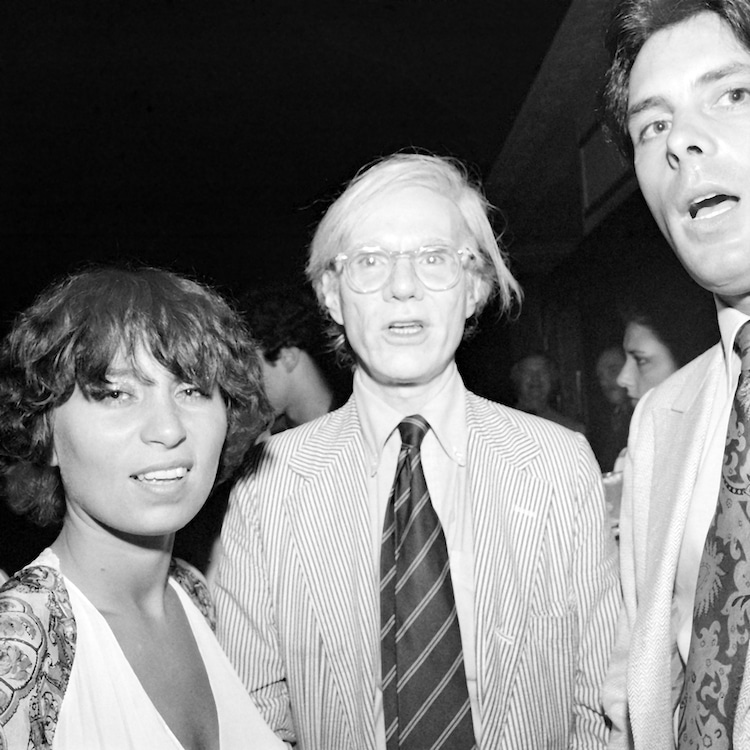

Open Mouthed Judith, Andy Warhol, and His Friend. Studio 54, July 1979.

Your photographs celebrate not only the glitz and glamour of the time, but a feeling of camaraderie between party goers. How did you connect with your subjects?

I rarely went out alone. I went to the salsa clubs and artist/musician loft parties with my Rosner cousins and friends. At Mardi Gras, New Orleans '77, I met and befriended Judi Jupiter; we came back and started hitting CBGBs and the discos together. There were lots of regulars we’d see at different discos and we’d hang out and dance with or around one another. As mentioned before, my camera helped me talk to and meet people. I’d ask or gesture for permission to take a photo, and people usually replied yes.

How did you choose who to photograph given that on film, each shot is precious?

With the medium format camera, I had 12 exposures to a roll (and very little money to buy film). If my medium format camera was in repair, then I'd have a 35mm with 36 exposures. I learned to be very selective, photographing people, places, and circumstances I found visually dynamic, iconic or ironic.

My dad Jack Meisler was a printer by trade, and a passionate photographer. I inherited his “eagle eye.” To this day, even when using a digital camera, I find my first shot in a sequence is usually the best. I’m back to using B&W film with a medium format camera and glad to be more selective and trust my instincts.

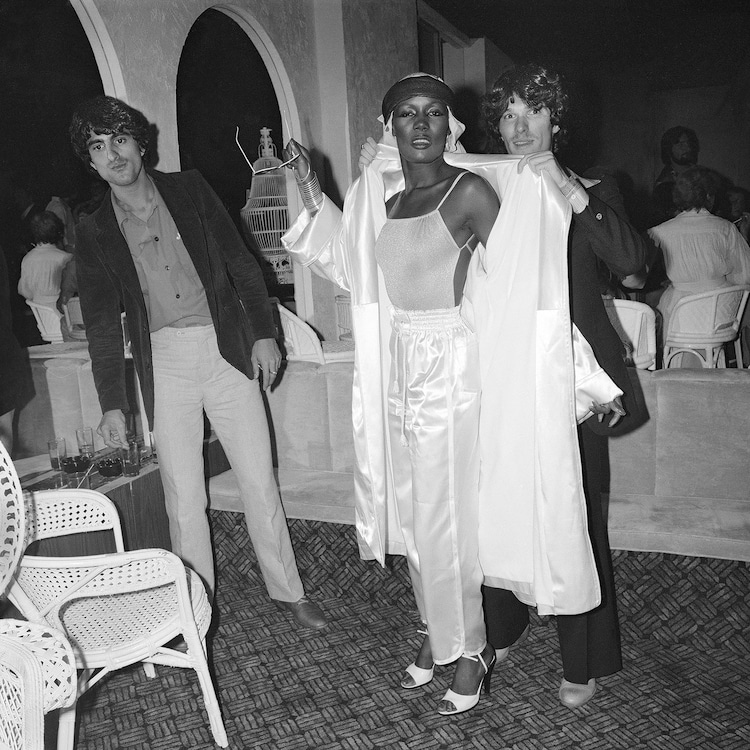

Grace Jones Arrives on Opening Night. La Farfalle, June 1978.

Nightlife staples Grace Jones and Andy Warhol are both featured in your archive. How do you think celebrity has changed from that era to now?

Celebrity is a fleeting notion, affected by publicity, media, time, and culture. Some celebrities have staying power, others burn out or are forgotten within a short time. The celebrities hung out amongst the other party goers in the clubs I frequented in the '70s. For my generation, I think celebrity changed December 08, 1980 when John Lennon was killed.

What does celebrity mean when we have Celebrity Apprentice TV host in the White House who bragged “I'm automatically attracted to beautiful [women]—I just start kissing them. It's like a magnet. Just kiss. I don't even wait. And when you're a star they let you do it. You can do anything … Grab them by the pussy. You can do anything.” Celebrity has taken on a tarnished meaning, to me.

CBGB. April 1977.

Any particular stories from your disco experiences that you’d like to share?

Note this is an excerpt from Meryl's book, “A Tale of Two Cities: Disco Era Bushwick”

July 13, 1977 was to be a momentous evening at Studio 54. One of the owners invited Judi, ostensibly to see our work, to be his personal guest. But if you invited Judi, Meryl came along. Oh yes, I was excited – we were gaining entrée to the legendary private rooms reserved for the stars!

But while getting ready at my place – BAM! The lights went out in my building…and all the surrounding we got on our bikes and rode downtown on dark streets, headlights glaring at us from all directions as we paused at Columbus Circle. At Studio 54 a few stragglers waited outside, but the doors were locked. We pounded, but no reply. Waited a while, pounded some more. But it was the real thing, a big black out, maybe even as big as the one I’d experienced in 1965.

In the following days, New York felt like a small town. I photographed people hanging out on the street as headlines and radio blasted news about a place I never heard of before – Bushwick. It was burning, with looting and rioting that went on and on. A few days later, we were back partying at Studio 54, lights blazing, life back to normal, but not so in the hellhole called Bushwick.

Drying Hands in the Ladies Room. Studio 54, July 1977.

For a long time, your archive remained unpublished. What drove you to finally show your work publicly?

I’ve always exhibited my photographs and artwork but never had many articles nor a book published until 2014. The vast majority of my archives are still yet to be revealed. After studying with Lisette Model at the New School, 1975-76, I enrolled in a photography book course with Bob Adelman. He set me up with a writer to submit a proposal with my Long Island photographs to a publishing company he was associated with, and the proposal was ultimately not accepted.

I kept doing the series anyway, and in 1978, the work successfully helped me receive a C.E.T.A. (The “WPA of the 1970s”) Artist position as a documentary photographer for the American Jewish Congress. I created a photographic archive of Jewish New York for AJC, which also included my personal project, interviewing and photographing extended family members to learn about my Eastern European Jewish roots and immigrating to the USA.

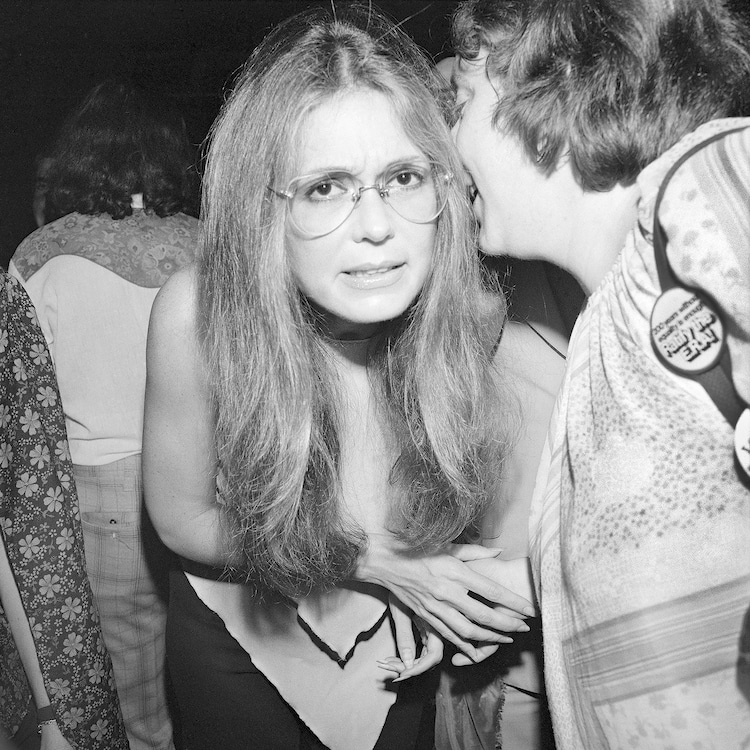

Woman With Ratify The ERA Button and Gloria Steinem. Studio 54, July 1977.

Throughout my 31-year career as a NYC public school art teacher, I always worked on my “own artwork” – continuously exhibiting, applying for, and sometimes receiving, grants and commissions. I was always plugging away. The Disco, Go-Go and other “decadent” nightlife photos were never exhibited. It could have put me at risk of losing my job and means of livelihood.

Upon retirement from the NYC public schools in 2010, I had more time to focus on getting my work “out there.” In 2012 and 2013, I submitted a proposal for a book about my 1980s Bushwick photographs to several publishers and was a finalist for a major first book award. I turned down a vanity press offer. Another publisher was waiting to make decision when Jean Stéphane Sauvaire of Bizarre Bushwick offered to exhibit my work at Bizarre during Bushwick Open Studios 2014 and publish it.

A Tale of Two Cities: Disco Era Bushwick (Bizarre Publishing 2014) and Purgatory & Paradise SASSY ’70s Suburbia & The City (Bizarre Publishing 2015) changed my life and brought my work to an international audience. Now, I am working on the third book in this trilogy about the 1970s.

Boyz to Men. Bushwick, October 1982.

Eventually, you transitioned into a long teaching career and began photographing Bushwick, where you were teaching. How was Bushwick different to what you were seeing in Manhattan?

I visited and photographed many neighborhoods in the 1970s and early ‘80s that were deemed “unsafe” at the time including East Harlem, East Village, Lower East Side, East New York and The South Bronx- none of them fully prepared me for the Bushwick I encountered.

Note, the following is an excerpt from “A Tale of Two Cities: Disco Era Bushwick,” where Meryl describes Bushwick from her perspective at the time

On my first day, rising from the subway, I actually wondered if the previous art teacher had been killed. All around me was a wasteland of broken bricks, crumbling concrete, and fallen timber – cooled ember vestiges after the ashes of arson had blown away. I.S. 291 was one of the few functioning structures on the block and felt like a hybrid: part school, part shelter, part prison. It was bewildering: kids trying to learn and enjoy day–to–day childhood life in the midst of chaos and despair; amazing teachers whose sense of duty provided structure and purpose within the cinderblock fortress of a shattered neighborhood. To me, the natural light of the area was so beautiful, the kids were kids, and the vacant buildings practically whispered stories. I stayed, and taught in Bushwick from 1981 to 1994. It was never boring.

Walking to and from the subway each day was an adventure. There was no telling who would be hanging out or what would show up on the street or in a rubble-strewn lot. I took pictures in my mind, but wasn’t so quick to bring a camera because the previous year, on the last day of school, an intruder to my Lower East Side classroom threatened to shoot if I didn’t hand over my beloved Norita Graflex. But by February 1982, I could no longer resist, and began carrying an inexpensive plastic point-and-shoot with cheap transparency film developed in the least costly way.

My route was rhythmic and limited: in the morning I the subway or my parked car, discovering that each street had its own distinct ambiance and stories to tell. My classroom was windowless, but if subbing in a room with a view, I took the little camera. The images are like winks, quick sketches of the people and places in this small section of Central Bushwick during a desperate decade. Some of the people were kids I knew from school, but most were strangers I encountered and politely asked permission from. The buildings always stood waiting for their portraits, never knowing when they could stand no more.

Roller Skates. Bushwick, circa 1984.

Obviously, Bushwick has undergone a huge transformation in recent years. Do you have any thoughts about its rise as a symbol of gentrification?

Bushwick’s rise from a low point in the 1970s and 1980s was made possible in large part by local community input and planning and city/government assistance. I don’t miss burnt out buildings and empty lots filled with unsafe debris. The new housing that rose in their place during the 1980s to 2000 were built in scale with the existing architecture with people's living comfort in mind. The dangerous deserted parks were revitalized. I always thought that Bushwick had beautiful light, had good public transportation, and the people I came to know in my walks and working there from 1981-1994 were in general warm and welcoming. This was a natural draw, especially to new immigrants and creative people seeking affordable places to live and work.

The greatest danger of gentrification, in my opinion, is the real threat to what is already an inadequate supply of affordable housing, resulting in displacement of longtime and newer residents alike. To be vested in a community and keep it vital, people of various incomes need to be able to set down roots for themselves and future generations.

Gentrification on the onset might help commerce but eventually, in my opinion, destroys small family-owned businesses small business that make a neighborhood unique. As a daughter of a small business owner, I think small businesses (including working artists and craftspeople) need long-term renewable leases and rent protections as well. Diversity and opportunity for all kinds of people is the strength of this city; making it a place for only the wealthy will destroy the character of NYC.

Liberace's Protégée. Le Mouches, April 1978.

What do you hope that people take away from your images?

Everyone you meet, even if for a moment, is important. Treat them as such. We are all witness to and part of history. This is your time, this is your place. Eventually, you will find your purpose and passion. To paraphrase Isaac Newton—we stand on the shoulders of those who came before us. What you say, do, preserve, change and share matters.

Wild Wild West Kiss. Hurrah, March 1978.

Feminine Floored. Hurrah, March 1978.

Meryl Meisler: Website | Twitter