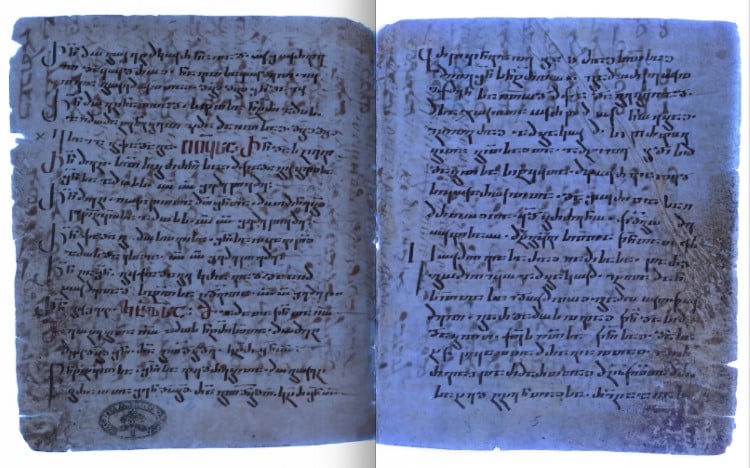

Photo: © Vatican Library

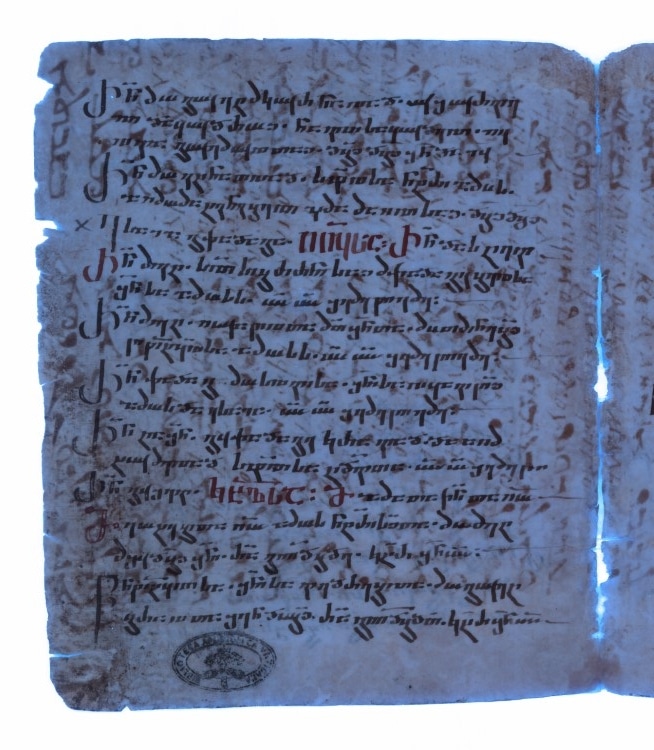

Recycling isn't something new. For thousands of years, different cultures have gotten creative about using the materials they had on hand. This includes medieval scribes, who were responsible for writing important manuscripts. When materials were scarce, they would look for existing texts considered to be of lower value and wash or scrape the ink off the pages. Then, they'd go about writing a new text on the fresh, blank pages. The result is something that modern scholars call palimpsest manuscripts. Incredibly, UV light can be used to reveal the invisible text—a beautiful marriage of technology and classic research.

This has led to amazing discoveries. Most recently, medievalist Grigory Kessel from the Austrian Academy of Sciences was studying a manuscript in the Vatican Library when his UV light brought forth something spectacular. Hidden under two layers of text was a previously unknown chapter of the Bible. Written in Old Syriac over 1,500 years ago, the fragment of text is a more detailed version of Matthew 11-12 in the New Testament.

“The tradition of Syriac Christianity knows several translations of the Old and New Testaments,” shared Kessel. “Until recently, only two manuscripts were known to contain the Old Syriac translation of the gospels.”

Photo: © Vatican Library

The discovery is important because it offers new insight into the history of the Gospels and how their stories were transmitted. The Old Syriac version, which was written at least a century before the oldest Greek translations, offers subtle nuances that are missing from the standard version that most people are familiar with.

For example, while the original Greek of Matthew chapter 12, verse 1 says: “At that time Jesus went through the grainfields on the Sabbath; and his disciples became hungry and began to pick the heads of grain and eat,” the Syriac translation says: “[…] began to pick the heads of grain, rub them in their hands, and eat them.”

The translation that Kessel discovered was first written in the third century CE and copied in the sixth century CE. Its discovery is part of the Sinai Palimpsest Project, where researchers seek out these palimpsest manuscripts in order to recover important information hidden in the recycled materials.

For Claudia Rapp, director of the Institute for Medieval Research at the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Kessel's discovery solidifies the vital role that technology plays in academia. “This discovery proves how productive and important the interplay between modern digital technologies and basic research can be when dealing with medieval manuscripts.”

h/t: [IFL Science]

Related Articles:

A Look at the Earliest Printed Book—and It’s Not the Gutenberg Bible

World’s Most Famous Medieval Illuminated Manuscript Now Viewable Online

Rare Book Collector Reveals Tibetan Book Printed Before the Gutenberg Bible