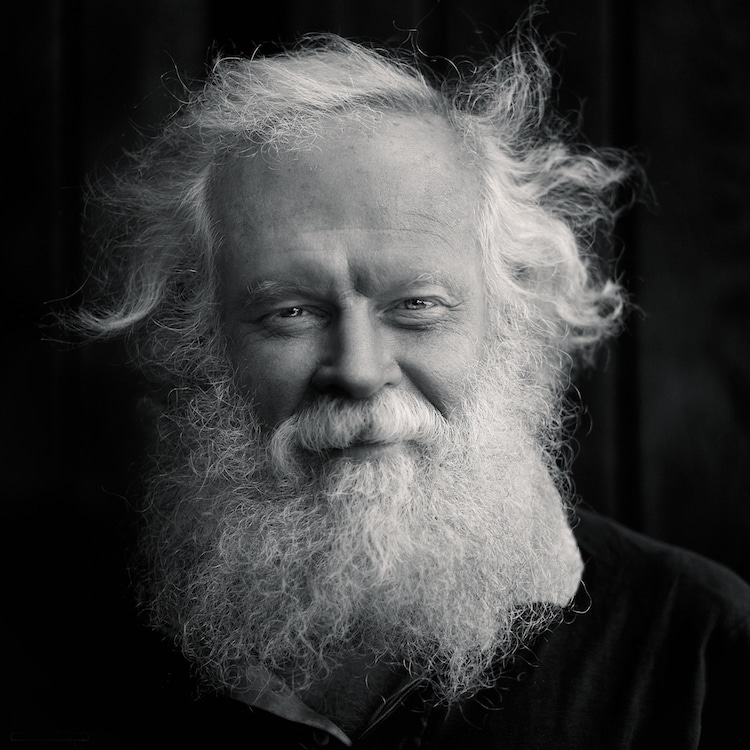

Mark or Philipe.

Brazilian photographer Pedro Oliveira began his journey with photography upon moving to the United States to pursue his education. In a short time, his work has gained high acclaim, with his series about homelessness Careful: Soul Inside garnering him awards and international press.

In this moving series, which he began in June 2015, Oliveira couples soulful portraits of his subjects with their stories to bring awareness to the larger social issue of homelessness. If one can imagine that, in the United States, on a single night half a million people experience homelessness—meaning they either sleep on the street or in a shelter—and that in 2016, 16 states reported increases in the homeless population, more than ever these stories need to be told.

We had a chance to speak with Oliveira about his work and what motivates him to share these stories. To read the full story behind each portrait, visit Oliveira's website.

King James. We talked for a bit about it and he seemed really interested in photography. After a while I asked if he would mind me taking a picture of him. Very shy, by first, he didn't agree. I asked then, if he would take a picture of myself. He was a little afraid of dropping the camera, but his curiosity likely spoke louder, and he agreed to take the picture. The picture was the ice-breaker and I after taking my portrait, he allowed me to take this one.

Can you tell us a bit about your background with photography?

I started photography “by accident.” Before three years ago, I had never taken a picture. Portland rains a lot, and I had just moved here. The weather was getting to me, and I was going through a very bad crisis of homesickness, when a good friend of mine from Korea suggested that I buy a camera. I couldn’t see a reason for a camera, but did it anyway. I immediately fell in love with all things photographic.

I am a senior in Communication and Advertising at Portland State University, so I took some art classes there. However, I am mostly self and workshop taught. I am obsessed with Photoshop and color grading, so it was just a natural process.

Doug. I was just walking around downtown, looking for a place to get a cup of coffee, when Doug literally jumped in front of me, with the biggest smile I've seen and said “Here, why don't you shoot this?” while making a big silly face and holding an edition of the Street Roots, a local newspaper sold in Portland…

What motivated you to begin Careful: Soul Inside?

When my dad died, I was an 8-year-old boy. Mother was a housewife who suddenly saw herself alone having to provide for three children. We never became homeless, but had to live for a long time in what used to be the storage/garage space of our neighbor. So I can affirm that we experienced what it is like to live below the line of poverty. You can become practically invisible to society.

With homelessness, it is even worse, since there are so many other stigmas that society attaches to the homeless condition, such as being violent, lazy, drug addicted by option, etc. Raising more awareness of this ongoing issue was my main goal when I first started the project. I wanted to help tear down the barriers that society erects to isolate the less empowered and make them the “other.”

How many people would you say you’ve photographed over the two years of the series? Is it still limited just to Portland or have you branched to shooting in other cities?

I have between 30 and 50 subjects, I believe. I honestly don’t know the exact number. It became part of my day-to-day life and I do it all the time. Some of them are still to be published. It all started in Portland, but I have photographed all over the West Coast, as well as New York, Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, London, Copenhagen, and Amsterdam.

Veronika. As we walked around town, the conversation evolved. Veronica told me that no one but herself was to blame for her condition. She explained that it started during her early teens as a form of freeing herself but when she realized she had dove too deep to get back. “My parents still love me, but I am too embarrassed to get back home. I'm the one who decided to leave not them,” the girl confessed.

Is there a particularly memorable experience shooting the series that you’d like to share?

Several if not all of them are memorable. That’s why most of my subjects have a little narrative about the person. I don’t want people to just see a picture, but know who they are and what their stories are.

Perhaps the one who touched me the most was Veronika. I guess because she was my sister’s age, and very sharp (smarty-pants) just like I am. Veronika was addicted to heroin, totally aware of it and told me her parents tried to help her, but she was young and wanted some adventure. She even tried several times to stop, but so far has been unsuccessful. When I met her she was again doing it. It just breaks my heart thinking how dependent on drugs you can become once you are there.

Jake El Grande. “My name is John, but you can call me Jake el Grande (faking a Spanish accent) … you don't look like a photographer. What happens next (after the picture)? The cops will jump out of their hidden cars?”- John (Jake) a meth addicted and homeless person who lives around southeast Portland.

What’s the reaction of the participants when you show them their photo? How do they feel about the attention the work has received?

I don’t have the chance of showing the final work to some of them. The ones that I was fortunate enough to share with the subjects always received their positive reaction. Veronika even said she cried when I texted her result. She told me it was sad to see herself that way, but it was also very soulful and pretty. I never felt such a bittersweet feeling in my entire life.

The attention and criticism given to the photographs have been both positive and negative. All my subjects are fully aware of why I am taking the pictures. I let them know that they likely will be published and their stories told. They are mostly happy to help and understand and agree that this is a noble cause. Some people believe photographing homeless people is a form of exploitation. I disagree. I make no profit whatsoever from these portraits, and the subjects agree that this invisible social wall is something that should be addressed.

Glenn. I met Glenn (fictitious name) in downtown Portland while waiting for the MAX. I didn’t really know if he was a homeless person at first, but decided to chat with him anyway. Glenn told me that after having a life working in many different fields, he was laid off and that due to his age he could never get another job again and as a result, he ended up on the streets. This portrait's black and white version was a winner of two different portrait contests.

What’s the most common misconception, according to you, that people have when talking about homelessness?

As I mentioned before, the worst misconception is the idea that every homeless person is a bum, that they are all drug-addicted, and violent. After the financial crash of 2008, many people lost everything they had. The less comfortable financially literally ended up with no place to live. Glen, one of my subjects, summed up their condition pretty well when he told me: “Not all of us are bums, we only had bad luck. Most of society is one or two pay checks away from being where we are.”

How has this personal project informed your more commercial work, if at all?

I believe the main thing is the interaction with people. Most homeless people have never had their photographs taken, so a high degree of patience and detailed instructions shared with the subject are necessary for a good portrait. The dramatic aspect and color grading are obvious in my more artistic portraits as well.

Lastly, I believe learning how to work accurately at a fast pace is very important. Most homeless people are not willing to spend a long time being bossed around, so getting a precise shot quickly can be the difference between having a final picture or not.

Dean. Upon walking in the store the lady behind the counter seem uneasy, and a bit nervous. I felt she wanted to say something but was hesitant. “Are you ok, ma'am?” I asked. To which the barista replied:

“I know you have good intentions, but I don't want this guy around here. He is a troublemaker and is always being rude to our costumers. Earlier today he was shouting obscenities at a woman. Upon handing him the coffee, I asked about the incident. Dean explained: “I have no idea what she is saying, they get me confused with someone else all the time… there is someone around here, that looks exactly like me.”

What do you shoot with?

I am shamelessly a Canon boy. I started with a little Rebel T3i, and inevitably I moved to a full frame Canon 6D. I have been shooting with it for two years now, so it’s about time for another upgrade. I have been looking around, but a Canon Mark IV should be my best traveling friend. Regarding lenses, I normally shoot with Canon 85mm 1.2, 50mm 1.2 (my favorite lens), Canon 35mm 1.4 and Canon 24-105mm.

Dale. I didn’t have the chance to talk with Dale for more than 5 minutes, but he was with a friend who he claimed to be his only company and best friend. Dale was clearly a homeless person, but since he wasn’t really comfortable with me asking questions I decided to stop right there and only take the pictures.

Can you share a bit about your approach to getting people to open up and let you photograph them?

It is quite ironic the numbers of inquiries I get that ask me this very question: “What’s your secret?” People truthfully believe there is a magic bullet to it when actually there isn’t. I can report that more of my requests are rejected than accepted. I am very shy and it used to frustrate me a lot. After a while, I just understood that it wasn’t personal, and that “no,” means, “no.”

The one hint I can give is to talk with them just like you would with any other human being. It sounds weird I know, but some people unintentionally patronize their homeless subjects or suggest pity in their tone of voice. Just talk to them like you were talking to your friend, roommate or relatives. I lost count of how many neighbors from my building have passed by me with a confused look while I was sitting on the grass in the park having a vivid conversation with a homeless guy.

Sandra Reggan. Sandra is a Street Roots vendor that I met a couple of months ago. Always very polite and upbeat, what called my attention on Sandra was her style. She is always in my neighborhood and every time I see her, she is wearing a different fancy and stylish dress.

Compositionally the work is very tight, with little background context. What went into the decision to get so tight in on the faces?

I used to think that I had to isolate the environment and make the pictures all about the subject. Making the crop tight and getting rid of the background used to be the only way I knew how to do it, and that is what I judged to be the right thing to do. It is interesting that looking at them now in retrospect, I can see that my perspective has changed as a photographer.

On my latest project Ribeira, which I photographed in Brazil last year, you still can see examples of this style, but much lighter clarity while keeping the high definition and leaving the background as part of the story. Today I believe the environment is as important as the subject to tell a more complete story of what is happening.

Jimmy/James. I met Jimmy, while showing the result of “James: The King” to the other James. He was very friendly and claimed James as a good man and one of his best friends. While talking, Jimmy told me that he had a dream of becoming a journalist himself, but after awhile he dropped college, and for several reasons, he ended up on the streets. I had the chance to tell him about my now-project and he accepted being one of my subjects, so long his picture was taken in black & white.

What do you hope that people take away from your work?

I do photography for myself and to myself. I believe staying true to what you are passionate about is what makes you better, and that doesn’t apply only to photography. With this in mind, I really expect that people will be able to see the soul of my work and feel emotionally connected. My portraits are highly socially driven, so if they can make someone stop for at least a second and think a little more on issues that take him or her out of their comfort zone, I will have accomplished my mission.

Michael. “I tell you what, if you help me with “anything”, you surely can photograph me, my man. I can´t talk much about my life, though, cause it is so amazing that it was copyrighted. All I can say is that I live on the streets for 12 years, love drinking some 221 (rum), and people tell me I look very alike MD.House” -Michael. who was born in Montana and has lived on the streets for the past 12 years.

What are your wishes for the future of the series?

The cycle of Careful: Soul Inside is completed, and I likely won’t be photographing for this project for a while. Soul Inside is already internationally awarded and published, has been part of two art museum exhibitions, and was the subject of television articles. That’s way beyond what I ever imagined it would reach, and I am happy with it. I am now focusing on different projects and contemplating the possibility of others. All I can say for now is that I am about to start a great project related to women empowerment. Shhhhhh…that’s still a secret, don’t tell anyone (laughs).

Pedro Oliveira: Website | Facebook | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to use photos by Pedro Oliveira.

Related Articles:

Powerful Portraits Show the Homeless Dressed Up for Their Dream Careers

Homeless Man’s Unbelievable Makeover is a Life-Changing Transformation

Interview: Powerfully Raw Portraits of Homeless People by Lee Jeffries

100 Homeless People Were Given Disposable Cameras and This is What They Captured

Photographer Documenting the Homeless Discovers Her Own Father Among Them