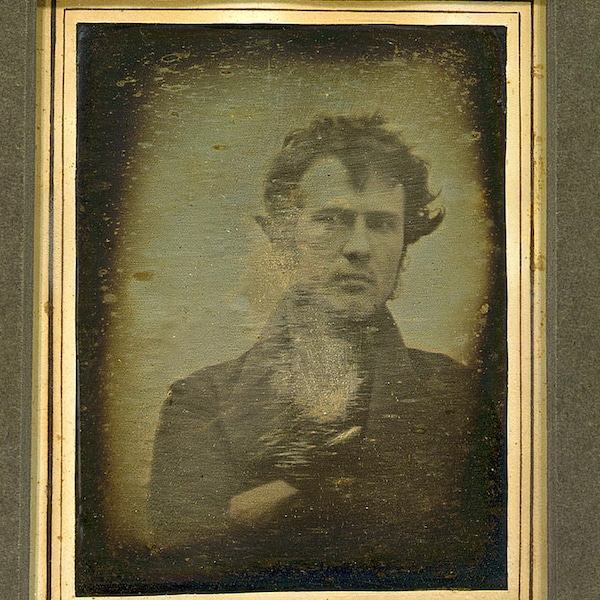

M’nông ethnic tribe

For many years, French photographer Réhahn has called Vietnam home. And over the past 7 years, he has worked diligently to do his part in preserving the legacy of the country's diverse ethnic tribes. For his Precious Heritage project, Réhahn is on a mission to photograph all 54 of Vietnam's recognized ethnic groups and share the beauty of their rich heritage.

According to the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGA), 14.6% of Vietnam's population belongs to one of these ethnic tribes, accounting for 13.4 million people. Though the Vietnamese government doesn't acknowledge them as indigenous people, they are recognized as ethnic groups. While the poverty rate among these tribes is significantly higher than the rest of the population, increased steps toward equality will help ensure a lasting legacy.

For Réhahn, who has photographed 51 of the 54 tribes thus far, Precious Heritage is more than a photographic series. By collecting traditional costumes and other ephemera from each tribe, as well as recording stories during his visits, he is helping preserve these cultures. In 2017, he opened the Precious Heritage Museum, a free space in Hoi An where the public can enjoy his photographs and the costumes, while learning more about the ethnic makeup of Vietnam.

We had a chance to speak with Réhahn about the motivations behind the project, his experiences meeting these ethnic tribes, and the difficulties of opening a museum. Read on for our exclusive interview.

Cham ethnic tribe

What inspired you to start Precious Heritage?

Even though I am not an ethnologist by trade, I’ve always been fascinated by people and their culture. When I moved to Vietnam, one of the first places I visited was Sapa. I intended to photograph the landscapes but instead, I was moved by the ethnic groups, such as the Red Dao and the H’Mong, who call this region home. I began my portrait series and slowly began to collect traditional costumes and artifacts, but it took several more years to craft the idea for the Precious Heritage Museum.

Dak Lak Ceremony

What's the most surprising thing you've discovered about the tribes during this journey?

I was really surprised, but also inspired, by a ceremony performed by the M’nông tribe in the Dak Lak region of Vietnam. The M’nông have a special connection with elephants, so much so that they actually welcome the animals into their village as a part of their family. I was able to witness the ceremony, which is performed once a year.

The tribe washes the elephant and then puts a series of things on the animal, such as pig’s blood, egg yolk, and rice alcohol, to bless it. The elephant then stands in front of the traditional M’nông stilt house as the tribe inside plays the gong to welcome it and wish it good health.

Red Dao tribe

When did you decide to also begin collecting other ephemera like traditional costumes and how do you feel this complements your photography?

In 2012, I bought my first costume from the Red Dao tribe. The Red Dao’s impressive costume is one of the more well-known ones internationally and it occurred to me that it would look nice presented in a gallery. At that point, I didn’t yet have a gallery, but it sparked my imagination. After that, I met the Co Tu people and they gave me a costume as a gift. Then I had two.

The idea of founding a museum, in which photographs, costumes, and artifacts of each of the 54 tribes would be displayed, started to turn in my head. I knew this was a project that would take a significant amount of time and back then I wasn’t sure whether I could accomplish it. So I quietly made it my personal mission to see how far I could get. Now, I am actually on a photographic journey to meet the last three tribes!

The costumes and artifacts are an essential part of my museum. To have something tangible to introduce to the world that the tribal people actually crafted with their own hands—this really honors their unique heritage.

Co Tu ethnic tribe

Can you share a bit of information about some of the favorite tribes you've photographed?

One tribe that I feel especially connected to is the Co Tu tribe. I live in central Vietnam in Hoi An, and the Co Tu lives nearby, so I am able to visit them often. They still have a very strong culture and they are seeking ways to maintain their heritage. I recently finished building a museum that will be entirely dedicated to them, so that they will have a place to protect their artifacts, costumes, music, and portraits. The museum will be free to the public but will also be open to the Co Tu to use as a community center for tribal events. The Co Tu Museum will officially launch in 2019.

What challenges are these tribes facing?

Many of the tribes are being confronted with new access to the modern world as roads are built closer and closer to their tribal lands. It is a challenge for the ethnic groups to try to find the balance between technology like smartphones and the internet, and the old ways of their culture. Some of their ancient traditions are already on the way to disappearing.

Everything has two sides. Tourism can help the tribes get more income for their villages but it can also change, and even erase, the culture. I am not an expert in the fields of anthropology or sociology so I can only relate what I see.

Lao ethnic tribe

Xo Dang ethnic tribe

What has been the reception by these groups when you arrive?

For the most part, the tribes have been extremely welcoming and curious when I arrive. There has been a bit of hesitation in a few ethnic groups but once I reveal my mission they tend to open up and welcome my questions and camera. They are often eager to speak about their culture and to present it to a foreigner who is interested in what they have to say. When they see their portraits they sometimes laugh, sometimes they are moved—it is always a special experience.

La Hu ethnic tribe

What do you hope to capture through your photographs of these ethnic groups?

I want to honor the beauty of the ethnic tribes, to reveal their strength, their differences, their pride. I also know from my travels that Vietnam is quickly in the process of changing and developing. I believe that it is important to create a record of Vietnam now. It is a rare moment in history to find a country so open to the world but still containing an incredible amount of diversity and untouched terrain.

Black H'mong from Sapa

Opening a museum is no easy task. What was the most challenging part of creating the Precious Heritage Museum?

The most challenging task by far was actually traveling to meet and photograph all of these ethnic groups! It has taken me more than 8 years to get this far in my mission, and though I am close to the end, I still don’t know how much longer it will truly take.

The other challenge was to gain recognition as a museum rather than simply a shop or a gallery. I am very proud of the museum, which spans a space of 500 square meters [5,382 square feet] in the Ancient Town of Hoi An. It is filled with hundreds of artifacts representing the culture of the ethnic groups. Each costume is accompanied by a portrait and a short text about my experience meeting the tribe.

Kho Mu ethnic tribe

What do you hope the public learns from this project?

It was important to me to have the Precious Heritage Museum be free to the public. I would like to spread the information about these groups to as many people as possible so that they can understand the diverse cultural identities of the groups represented. I also feel that, for the ethnic groups, there has not been much interest in their stories before. Seeing others taking note of their traditions may help them maintain them.

Red Dao tribe in Sapa

The Precious Heritage Museum in Hoi An is a free museum that combines Réhahn's photos of Vietnam's ethnic tribes with traditional costumes and information about each group.