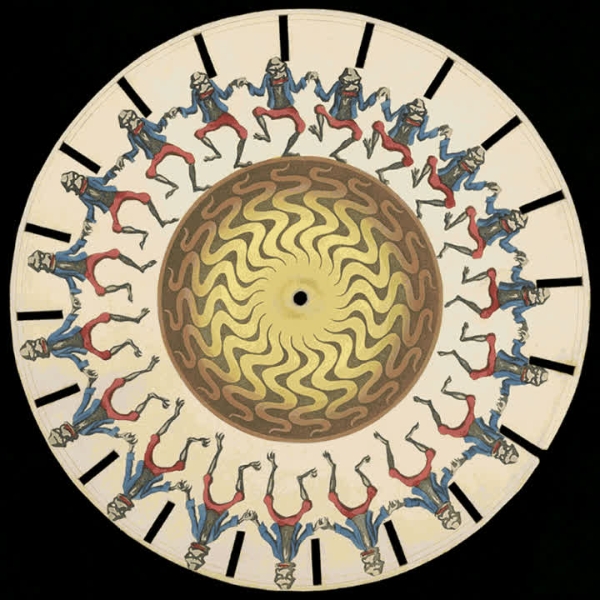

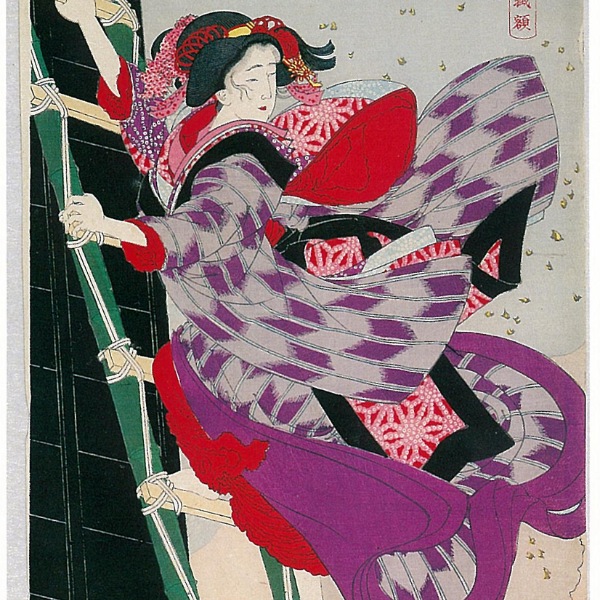

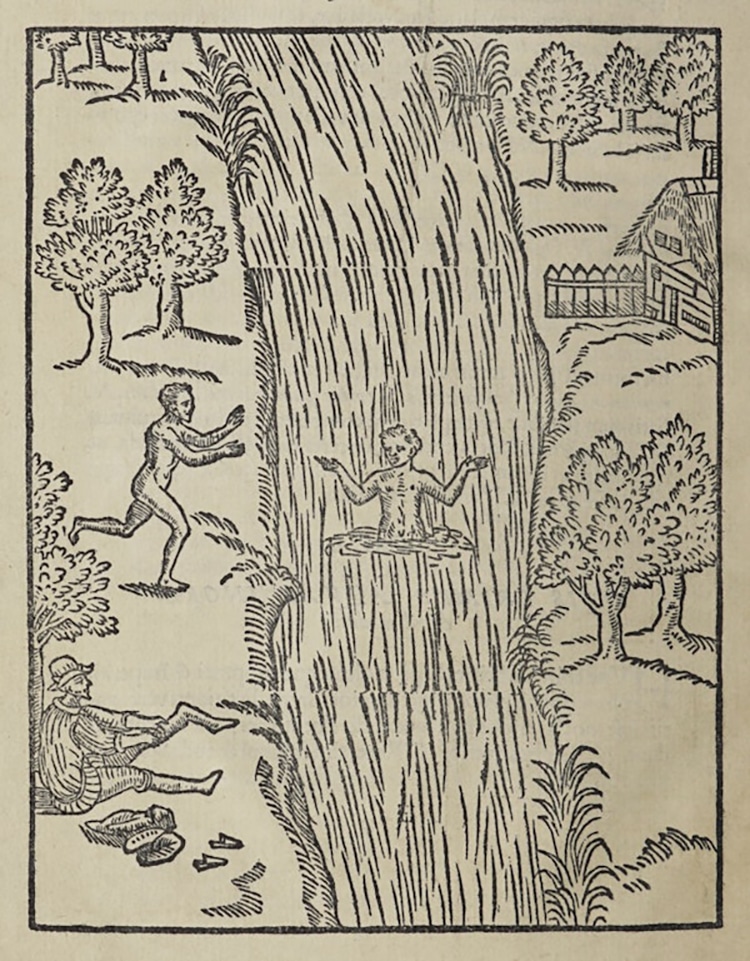

“De Arte Natandi (The Art of Swimming),” by Everard Digby, 1587. (Photo: Wellcome Collection via The Public Domain Review)

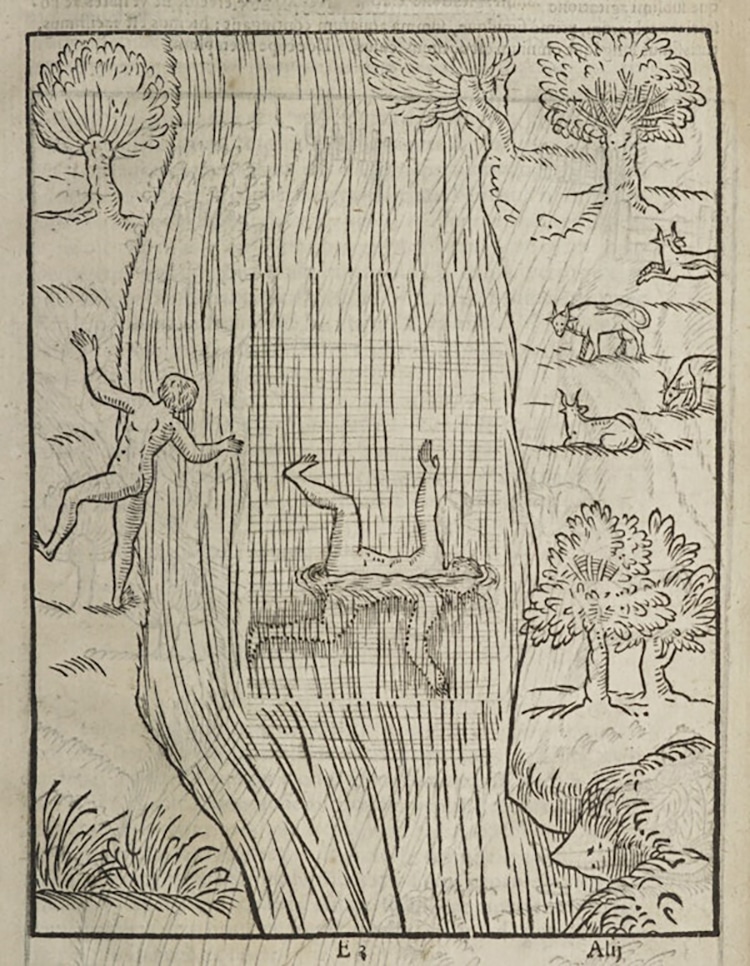

How did you learn to swim? Chances are your parents signed you up for swim classes at the local pool, or perhaps your grandpa took the old fashioned, ill-advised route of tossing you straight in to learn by necessity. Swimming is something that is often learned by doing rather than reading, but that wasn’t always the case. In fact, this practical skill has been immortalized in text. The earliest treatise on swimming in English was the translation of Everard Digby's 1587 tome entitled De Arte Natandi, or The Art of Swimming. With amusing woodcut illustrations, the odd book shows and describes how men and women might float, propel themselves, and otherwise frolic in the water.

Written by Digby, who was a theologian at Cambridge University, the book was originally published in Latin. An English translation followed, but the woodcut drawings would have been intelligible to anyone, regardless of their language abilities. Digby described the theory behind many strokes still taught today, such as “to swim like a dog,” “to tread the water,” and “to slide forwards upon his belly in the water.” His purpose is clear: safety first! He even describes the ways to properly enter and exit the waters, which are depicted much like the rRiver Cam in Cambridge, with which he would have been well familiar.

However, it was not just due to safety reasons that a 16th-century man or woman might wish to swim. The author noted, “Nor is it onely to be respected for this great helpe in extreamitie of death, but it is also a thing necessarie for euery man to vse, euen in the plea∣santest and securest time of his lyfe especially: as the fittest thing to purge the skinne from all externall pollutions or uncleannesse whatsoeuer, as sweat and such like, as also it helpeth to temperate the extreame heate of the bodie…”

He also stressed further health benefits grounded in the scientific ideas of the time, which linked health to humors: “If Phisicke be worthy of commendations, in respect of the nature in purging poysoned humors, dryuing away contagious diseases, and by this meanes adding longer date vnto the life of man, well then may this Art of Swimming come within the number of other Sciences, which preserueth the precious life of man, amidst the furious billowes of the law∣les waters, where neither riches nor friendes, neither birth nor kindred, neither liberall Sciences nor other Artes, onely it selfe excepted, can rid him from the daunger of death.”

If swimming was a science, it could be studied. However, certain strokes were deemed less worthy. This included those like the crawl which put the face in the water. All the same, swimming was natural. Later theorists of swimming would postulate it as a civilized practice, but for Digby it seems to have been more akin to the fish in its instinctiveness. Yet unlike fish, men and women could do so much more in the water. Think of Digby the next time you swim in summer, his identified ideal months for the activity, and feel free to peruse his antique text if you'd like tips on technique from over 400 years ago.

Everard Digbny's 1587 treatise on The Art of Swimming presents swimming as a science to be studied and practiced.

“De Arte Natandi (The Art of Swimming),” by Everard Digby, 1587. (Photo: Wellcome Collection via The Public Domain Review)

“De Arte Natandi (The Art of Swimming),” by Everard Digby, 1587. (Photo: Wellcome Collection via The Public Domain Review)

h/t: [Neatorama, The Public Domain Review]

Related Articles:

Shockingly Complete 1,100-Year-Old Hebrew Bible (aka Tanakh) Sells for Over $38 Million

Chilling Video Brings the Sounds of the Centuries-Old Celtic Carnyx Back to Life

These Are the World’s Oldest Languages Still Spoken Today

Why 1,200 Bone Pieces From 28 People Were Found in Benjamin Franklin’s Basement