Installation view of “Wu Chi-Tsung: Fading Origin” at Sean Kelly, Los Angeles. (Photo: Brica Wilcox)

For the Taipei- and Berlin-based artist Wu Chi-Tsung, art unfolds like a pilgrimage. It winds through contemporary forms; it dips back into ancient techniques; it stops to rest at an intersection between the two. Unlike a straightforward journey, the pilgrimage doesn’t simply conclude at a given destination but instead continues endlessly, collecting input and inspiration along the way. This is exactly why Chi-Tsung’s art production resists neat categorization, and straddles several artistic styles, moods, and methods.

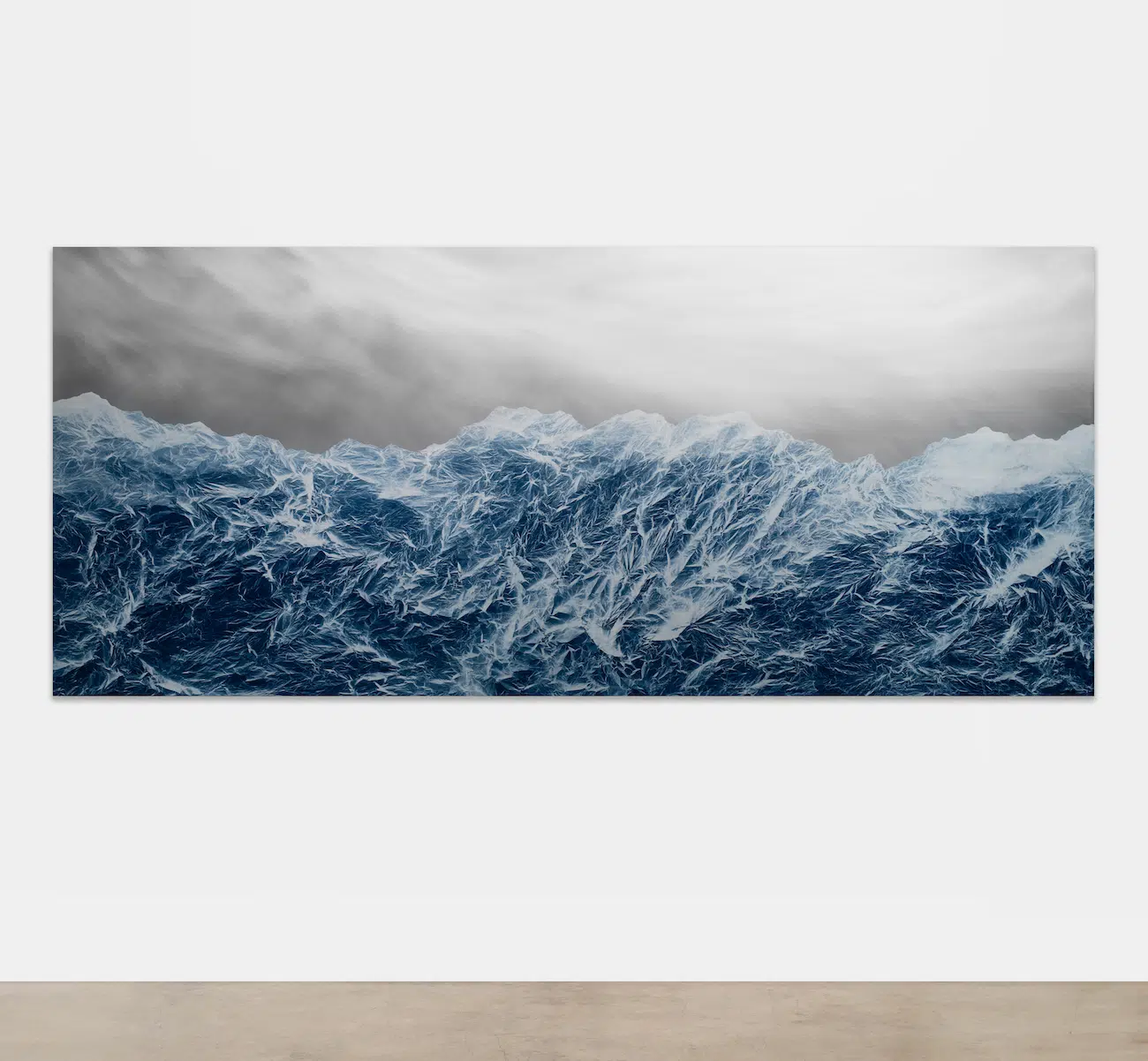

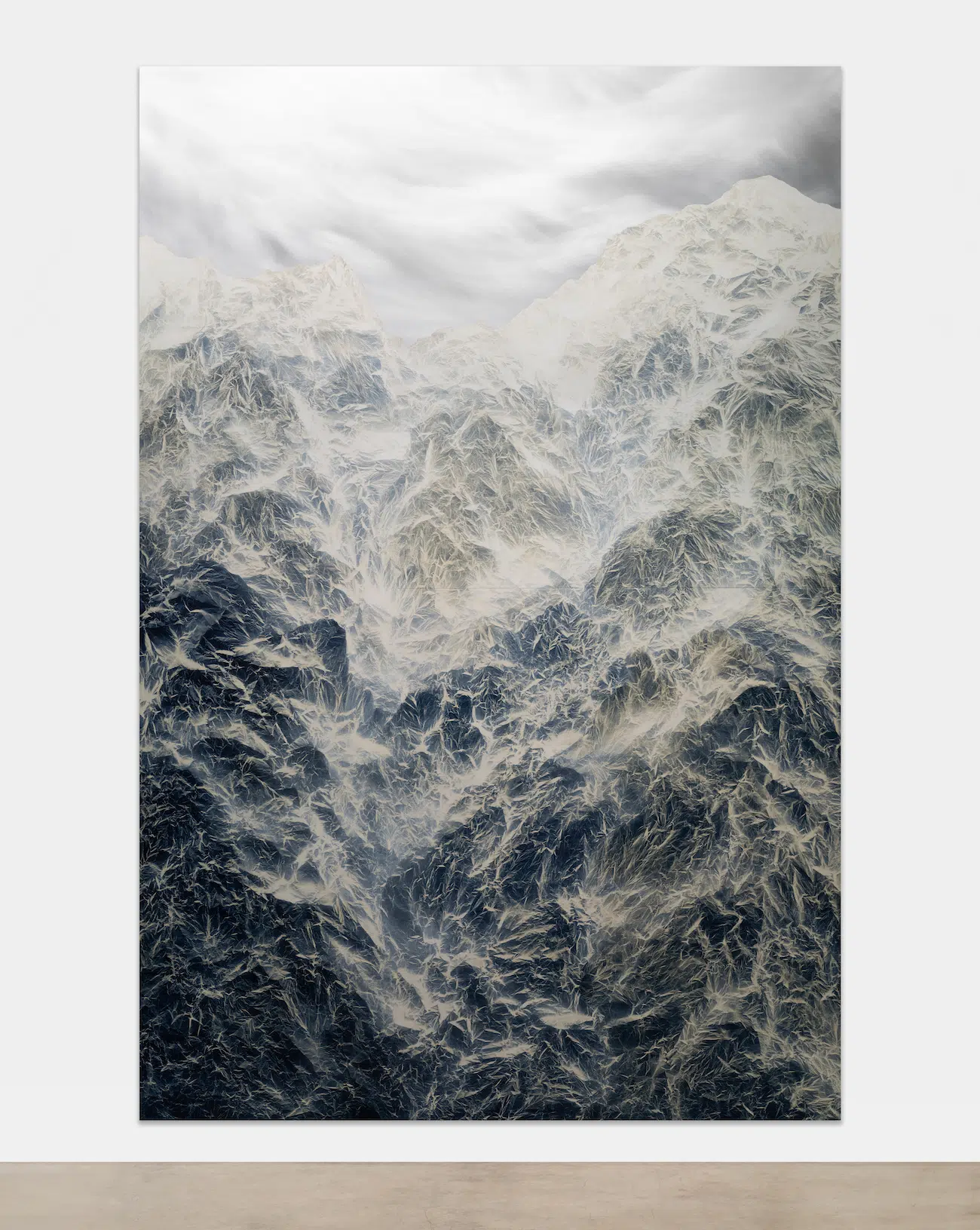

Staged at Sean Kelly Gallery in Los Angeles, Chi-Tsung’s newest solo exhibition, Fading Origin, poetically captures this sense of fluidity. The exhibition serves as the artist’s first in the city and perhaps as one of his most intimate, cataloging his relationship with cyanotypes, calligraphy, contemporary technology, and the contrasts between Western and Eastern art. Fading Origin focuses primarily on Chi-Tsung’s Cyano-Collage series and Wrinkled Texture works, both of which possess the serenity and monumentality of an ocean wave or towering mountain peak.

The Cyano-Collage series revisits the cyanotype—an early form of photography requiring only basic chemicals and sunlight—as digital tools have become increasingly common throughout art. To create these grand compositions, Chi-Tsung washed sheets of Xuan rice paper in photo-sensitive materials which, once dried, the artist creased by hand and exposed to sunlight. Some featured cyano-collages are dramatic and vast, while others are shrunk down to 2-foot squares as if peering through a window at a landscape in the distance.

Though similar, the Wrinkled Texture works interrogate notions of recursiveness. These diptych and quadriptych compositions begin with a single, full sheet of exposed cyanotype paper, which then becomes the basis for recursive cyanotypes within the same work. By double-exposing the paper, Chi-Tsung complicates the origins of each cyanotype, which, he explains, is a process that digital copies also undergo.

“[My] generation grew up at the intersection of the analog and digital worlds. The concept of an ‘original’ and the idea of ‘reality’ remain subjects of deep interest to me,” the artist says. “For younger generations, there is little distinction between one digital copy or a million copies.”

My Modern Met had the chance to speak with Wu Chi-Tsung about analog and digital art, the differences between Western and Eastern aesthetics, and the experience of mounting his first solo exhibition in Los Angeles. Read on for our exclusive interview with the artist.

Installation view of “Wu Chi-Tsung: Fading Origin” at Sean Kelly, Los Angeles. (Photo: Brica Wilcox)

What originally drew you to art as a career, and how did you develop your personal style?

I grew up practicing drawing, painting, and calligraphy from a young age, exploring both Asian and Western traditional painting styles. While I enjoyed it very much, I never intentionally chose art as my career.

As a teenager, I aspired to become a professional rock climber and trained intensively for two years—until I injured my fingers. That marked the abrupt end of my very short sports career. Since then, I’ve had to pursue my second choice: art. And here I am, still doing it! Haha, just kidding—I’m truly grateful to be an artist!

Everyone’s sense of aesthetic form is unique, and naturally, distinct branches and blossoms will grow from this foundation. Many artists focus on the artistic forms they like or desire, which can easily lead them into a self-referential loop where they lose their direction. In contrast, my approach is to think about what unresolved issues exist in the art world and how I can contribute. This belief often guides the development of my work, preventing me from getting lost—because, in reality, there are countless possibilities in artistic creation, and one could take any path.

The internal logic of Eastern/East Asian culture is also different—it tends to innovate through gradual integration within a tradition. It is no wonder that, over time, it has lost some of its vitality. East Asian culture undoubtedly needs to learn from the West’s bold, pioneering spirit and undergo radical transformation. Conversely, the East Asian way of thinking might also help the contemporary art world, which is predominantly shaped by Western perspectives, to develop a broader vision that accommodates both tradition and diverse cultures.

Installation view of “Wu Chi-Tsung: Fading Origin” at Sean Kelly, Los Angeles. (Photo: Brica Wilcox)

Wu Chi-Tsung, “Cyano-Collage 229,” 2024 © Wu Chi-Tsung Studio. (Courtesy of the Wu Chi-Tsung Studio and Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles)

What does it mean to be an interdisciplinary artist?

My art practice naturally crosses different media and art forms. Perhaps it’s because I’m not satisfied with a single mode of creation—I’m always searching for new possibilities of expression. However, it’s never about change for the sake of change; rather, each shift arises from the necessity to solve a specific problem.

For example, I have a deep appreciation for ink painting and calligraphy, especially the aesthetics, atmosphere, and spirit they embody. Yet these art forms have become increasingly distant from contemporary life, making it difficult for audiences to connect with them. This led me to explore whether I could replace traditional brush and ink with more familiar visual tools, reinterpreting these classical artistic forms and aesthetics in a way that allows viewers to engage with them more easily. Perhaps, through my work, audiences can also discover new ways to appreciate traditional art, enabling its continued evolution.

With this approach in mind, I have naturally developed various forms of artistic expression, such as video, mechanical installations, and experimental photography, all of which revolve around the theme of traditional ink painting and calligraphy.

At heart, I still see myself as a painter, but there are already so many talented painters in the world that my contribution would be redundant. Instead, I ask myself: What makes me different? How can I contribute to the evolution of art and culture?

Installation view of “Wu Chi-Tsung: Fading Origin” at Sean Kelly, Los Angeles. (Photo: Brica Wilcox)

How has your training in Chinese calligraphy, Chinese ink painting, watercolor, and drawing impacted your artwork?

I grew up with academic training in both traditional Asian and Western painting, which remains a crucial foundation for my understanding of art. However, that education was heavily focused on painting techniques rather than creativity and inspiration.

During my university years, I found myself feeling lost. Although I deeply loved painting—both Eastern and Western styles—after years of rigorous technical training, I struggled to paint freely. As a result, I turned to new media art, exploring video art and kinetic installations. These diverse artistic experiments helped me break free from old constraints and allowed me to revisit traditional art from a fresh perspective. At the same time, the aesthetics and artistic spirit found in traditional art set my work apart from many contemporary art practices.

Because of these experiences, I became particularly aware of the differences between Eastern and Western cultures, as well as the gap between traditional art forms and contemporary artistic language. Bridging this divide became a subject of great interest to me, and I hope my art can serve as a bridge between East and West, as well as between the past and the present.

Wu Chi-Tsung, “Wrinkled Texture Fading Origin 012,” 2024 © Wu Chi-Tsung Studio. (Courtesy of the Wu Chi-Tsung Studio and Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles)

What was the process of mounting Fading Origin, and what’s the significance of it being your first solo show in Los Angeles?

Los Angeles and California are major centers for Asian American communities, naturally blending Asian cultures with Latinx, African American, and various European influences. The region is also home to groundbreaking technological innovations and artistic creations, making it a vibrant melting pot. This spirit of cultural fusion aligns closely with the core essence of my artistic practice.

In the past, I have participated in several group exhibitions in California, and I’m honored that some of my works have been collected by top art institutions in the state. I’m, therefore, especially thrilled to present my solo exhibition at Sean Kelly Gallery in Los Angeles and to share my recent works with art lovers in the city. I also hope that my artistic pursuit—bridging Eastern and Western cultures as well as traditional and contemporary artistic languages—resonates with audiences living in LA’s diverse cultural landscape.

This solo exhibition focuses on two series related to cyanotype photography—Wrinkled Texture and Cyano-Collage—as well as a brand-new kinetic interactive installation: Calligraphy Study 003.

I began working with cyanotype in 2012 out of dissatisfaction with digital photography. While digital cameras, Photoshop, AI-assisted tools, and printing technologies allow for the rapid and mass production of images, they ultimately remain just one approach to photographic creation. I started searching for older and more direct photographic techniques that could integrate various materials. Cyanotype, which reacts only to strong ultraviolet light and requires sunlight exposure rather than a darkroom, captivated me with its unique connection to nature.

The exhibition title Fading Origin comes from a sub-series within Wrinkled Texture. Our generation grew up at the intersection of the analog and digital worlds. The concept of an “original” and the idea of “reality” remain subjects of deep interest to me. For younger generations, there is little distinction between one digital copy or a million copies—cyberspace, virtual reality, and artificial intelligence are their reality and the future of human civilization. This creates in me a sense of urgency—a desire to document these transitions and help future generations understand and imagine the past. The Fading Origin series was born out of this motivation.

Although I work in the contemporary art field, I don’t care much about what is “contemporary.” What truly matters to me is “art.” I constantly ask myself: what remains constant in this rapidly changing world?

Wu Chi-Tsung, “Wrinkled Texture Fading Origin 009,” 2024 © Wu Chi-Tsung Studio. (Courtesy of the Wu Chi-Tsung Studio and Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles)

What kind of pieces did you most want to highlight in the exhibition, and why?

I’d like to take a moment to talk about one of the key works in this exhibition—Calligraphy Study 003, a kinetic installation.

I started practicing calligraphy when I was around seven- or eight-years-old, but, to be honest, I didn’t enjoy it at first. I never understood why I had to copy someone else’s handwriting—the expressive freedom of ink painting and Western art attracted me much more. However, a few years ago, I had a sudden urge to pick up calligraphy again during my free time. I chose to practice with Wang Xizhi’s “San Luan Tie,” a letter he wrote to a friend, expressing his sorrow and helplessness in a time of chaos.

As I wrote, I found myself reading his words aloud, and I suddenly felt the raw emotions embedded in his strokes. It was as if I could see Wang Xizhi, a thousand years ago, sitting at his desk, overwhelmed with grief. That was the moment I finally understood the power of calligraphy—how writing is not just about form but about capturing one’s emotions and spirit.

Unfortunately, in today’s world, where we rarely even pick up a pen, let alone a calligraphy brush, this form of expression is gradually fading away. That realization made me want to explore calligraphy through my art, hoping to help more people experience this unique artistic medium.

In Calligraphy Study 003, a 3.6-meter-tall rotating fabric wheel slowly turns. Next to it, a brush and water are provided, inviting visitors to participate. The surface of the wheel is coated with a special moisture-sensitive ink that turns black upon contact with water but gradually fades back to white as it dries—causing the written traces to disappear over time.

On the floor, there is a red foot pedal switch. When pressed, the wheel rapidly accelerates to a dizzying speed, making it almost impossible to write. This acceleration is intended to convey a sense of violent speed, symbolizing how calligraphy—a tradition born in an agricultural society—feels completely out of place in today’s fast-paced world.

I was delighted to see many visitors engage with the installation for long periods, especially children—it may have been their first time holding a calligraphy brush to write or paint.

Wu Chi-Tsung, “Cyano-Collage 230,” 2024 © Wu Chi-Tsung Studio. (Courtesy of the Wu Chi-Tsung Studio and Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles)

Wu Chi-Tsung, “Cyano-Collage 226,” 2024 © Wu Chi-Tsung Studio. (Courtesy of the Wu Chi-Tsung Studio and Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles)

How is the exhibition exemplary of your work as an artist?

As a visual artist, a solo exhibition is the most important platform to showcase my artistic practice, and I always strive to provide audiences with a rich, immersive physical experience as they walk through my show.

Most of my cyanotype works on Xuan paper are either mounted in frames or attached to panels, which means audiences don’t get to directly experience the texture of Xuan paper itself. Because of this, I intentionally left one work, Fading Origin 002, unmounted, featuring four large sheets of Xuan paper hanging freely on the wall. As visitors walk past, the paper gently sways with the air, allowing them to feel its delicate, sensitive nature in a direct and tangible way.

Nowadays, we can easily view art from all over the world through the internet, so why do we still need to be physically present at an exhibition? Because some things can never be replaced, especially the bodily experience and the immediate, intuitive sensations of being in that space. I believe this is what makes exhibitions meaningful.

Wu Chi-Tsung, “Cyano-Collage 228,” 2024 © Wu Chi-Tsung Studio. (Courtesy of the Wu Chi-Tsung Studio and Sean Kelly, New York/Los Angeles)

Installation view of “Wu Chi-Tsung: Fading Origin” at Sean Kelly, Los Angeles. (Photo: Brica Wilcox)

What do you hope people will take away from the exhibition and your work as a whole?

I hope that those who pick up the brush and interact with the Calligraphy Study installation will experience the charm and joy of calligraphy, inspiring them to develop a deeper curiosity and appreciation for it. At the same time, I hope it allows them to reflect on the relationship between the body, writing, and speed in a more profound way.

I also hope that those who view my cyanotype works will realize that something as ordinary as wrinkled paper can unfold into a world of infinite possibilities when we engage it with our imagination. Perhaps this can serve as a reminder that everything in our daily surroundings holds endless potential for creativity and discovery.