Photo: SergeyNivens/Depositphotos

Humans visiting Mars will likely happen within the next 15 years. However, it will be a nine-month-long journey one way. Finding a way to feed humans on Mars is, therefore, critical before anyone steps foot on the Red Planet. A recent study done by researchers in the Netherlands may have come up with a viable method for growing nutrient rich vegetables by drawing upon ancient farming techniques used by the Mayans.

While dehydrated food has become a staple of space missions, it's not an ideal method of feeding humans long-term. It is less nutritious than fresh food, and being able to pack enough for a Mars mission is unfeasible. Regular supply missions are not efficient economically, leaving agriculture as the best method to feed Mars-bound humans. Of course, with an atmosphere 100 times thinner, with more carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and argon than Earth's atmosphere, Mars isn't readily hospitable to our crops.

Building upon past studies, scientists at Wageningen University & Research are looking for ways to optimize plant growth. Centuries ago, Mayans started using a method of farming which involved intercropping. Their descendants still use this method today, resulting in drought and disease resilient farms. Intercropping, as opposed to monocropping, consists of multiple plant types being grown together in the same plots of land.

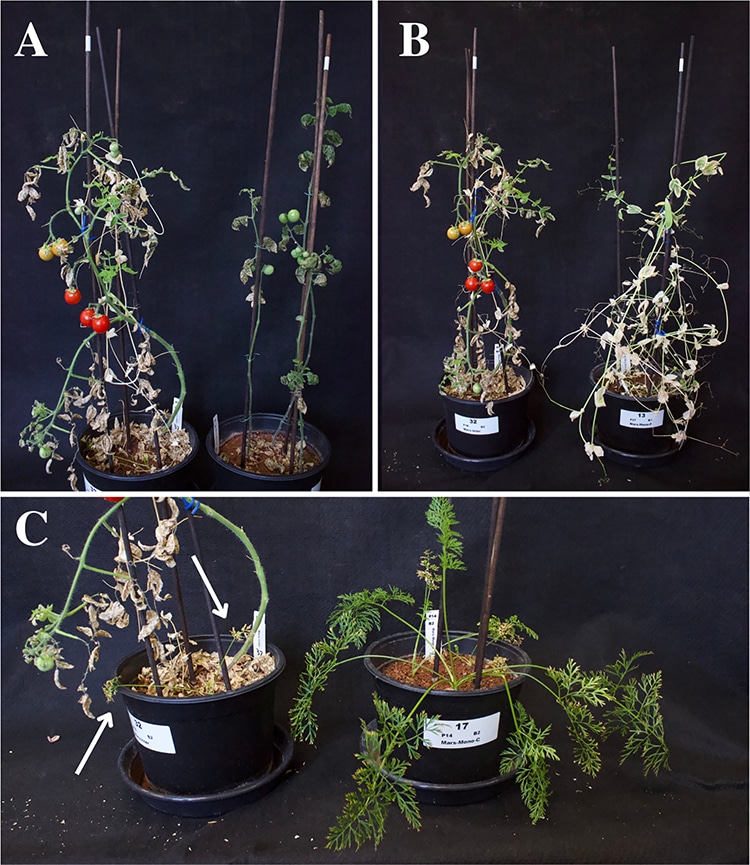

Researchers compared three different crops in an approximation of dusty Martian soil called regolith, as well as soil and river sand, both by monocropping and intercropping. Tomatoes, carrots, and peas were grown for 105 days. These three vegetables are high in nutrients that are destroyed during food dehydration. Also the researchers believed they would be complementary to each other. Tomatoes provide climbing support to peas and shade to carrots that are heat-sensitive, while peas “fix” nitrogen in soil by turning it into ammonia which becomes food for plants. Carrots, in turn, help aerate soil, thus improving water and nutrient uptake.

There were 60 pots total of plants, in greenhouses similar to what would be built on Mars. The results were then measured in terms of yield and nutrient density. In all three soil types, all the crops grew. Tomatoes did especially well in the intercropping regolith pot. They were higher in biomass, and impressively they had the most potassium of any of the tomato plants in the experiment. However, the peas and carrots were not fans of sharing a pot with tomatoes in the regolith, and produced decreased yields. There are several possible reasons for this. Tomatoes are known as “heavy feeders” likely taking nutrients from the peas and carrots. Additionally, a bacteria, Rhizobia, was added to the peas' plots to symbiotically work together for nitrogen-fixing. In the higher pH regolith, the Rhizobia failed to survive, resulting in the peas not being able to turn nitrogen into ammonia for its neighboring crops.

This study, however, was still promising to researchers, as they now think they can come up with ways to adjust the regolith so that it will be welcoming to intercropped plants. For instance, after the first harvest, they will be able to compost the unused parts of the produce to increase the nutrient value of the regolith. The study also provided evidence that intercropping would be beneficial to agriculture on Earth as well. With a rapidly changing climate, farming conditions are shifting, and soil is becoming sandier in some places. The intercropped plants did better in the river sand iteration than the monocropped pots. Not just astronauts on Mars, but many communities on Earth have plenty to learn from the Mayans.

Using Mayan farming techniques of planting different crops closely together could be beneficial for agriculture on Mars, and also on an Earth with its changing climate.

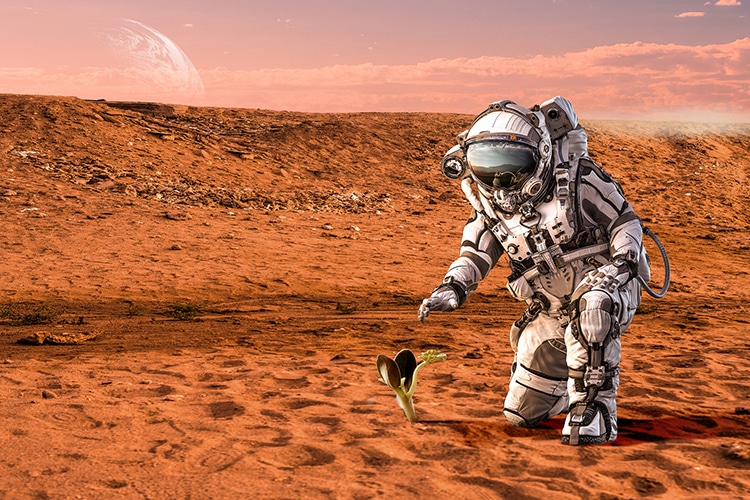

Comparison between intercropping and monocropping treatments in Mars regolith simulant.

A: Intercropping treatment (left) and monocropped tomato (right). B: Intercropping treatment (left) and monocropped pea (right). C: Intercropping treatment (left) and monocropped carrot (right). Arrows point to the small carrot leaves from the intercropping treatment. Pictures were taken on the day of harvest (day 105). (Photo: Gonçalves et al. / Plos One, CC BY 4.0)

Researchers point out that farming will be the most time- and cost-efficient method of feeding Mars colonists, but also will be a mental-wellness supporting practice.

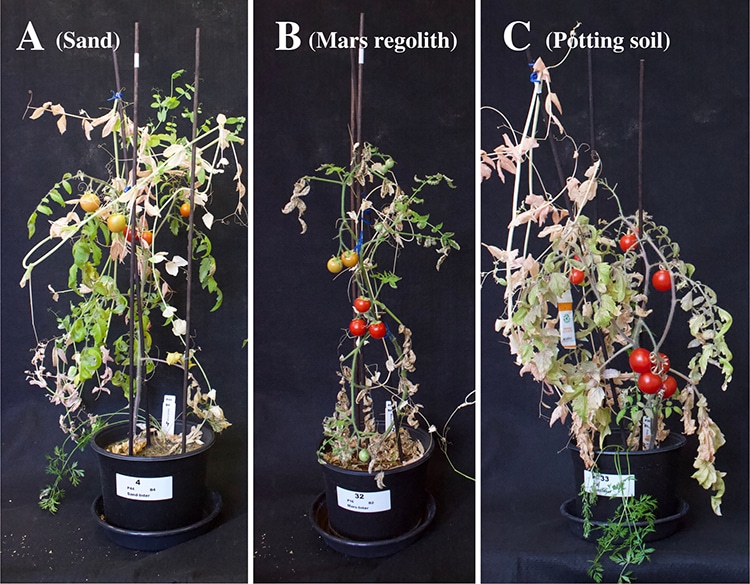

Comparison between intercropping treatment from the three soils.

A: Sand. B: Mars regolith simulant. C: Potting soil.(Photo: Gonçalves et al. / Plos One, CC BY 4.0)

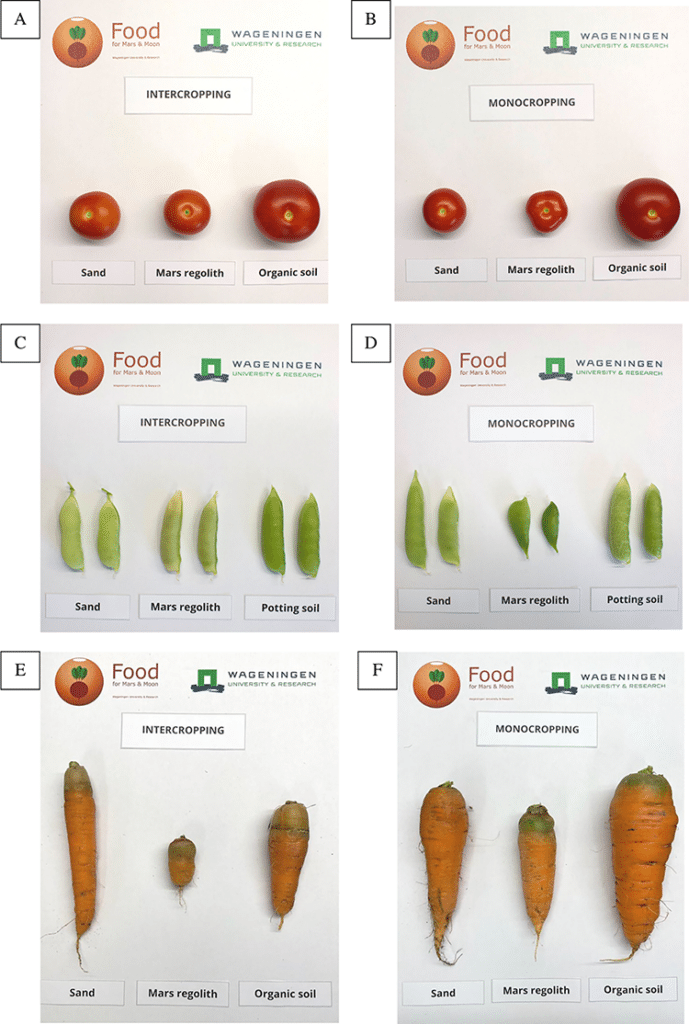

Yield comparison between cropping treatments and between soils.

Labels in pictures indicating “Organic soil” refer to the potting soil treatment. A: Intercropped tomato. B: Monocropped tomato. C: Intercropped peas. D: Monocropped peas. E: Intercropped carrots. F: Intercropped carrots. (Photo: Gonçalves et al. / Plos One, CC BY 4.0)

h/t: [Smithsonian Magazine]

Related Articles:

Scientists Discover Water Ice Deposits on Mars That Are More Than 2 Miles Thick

Seaweed Farming Offers a Solution To Fighting the Climate Crisis and World Hunger

Four Volunteers Entered NASA’s Mars Simulation Where They Will Live for Over a Year

Interview: Artists Map Out the Environmental Impact of Fish Farming in Eye-Opening Mosaic