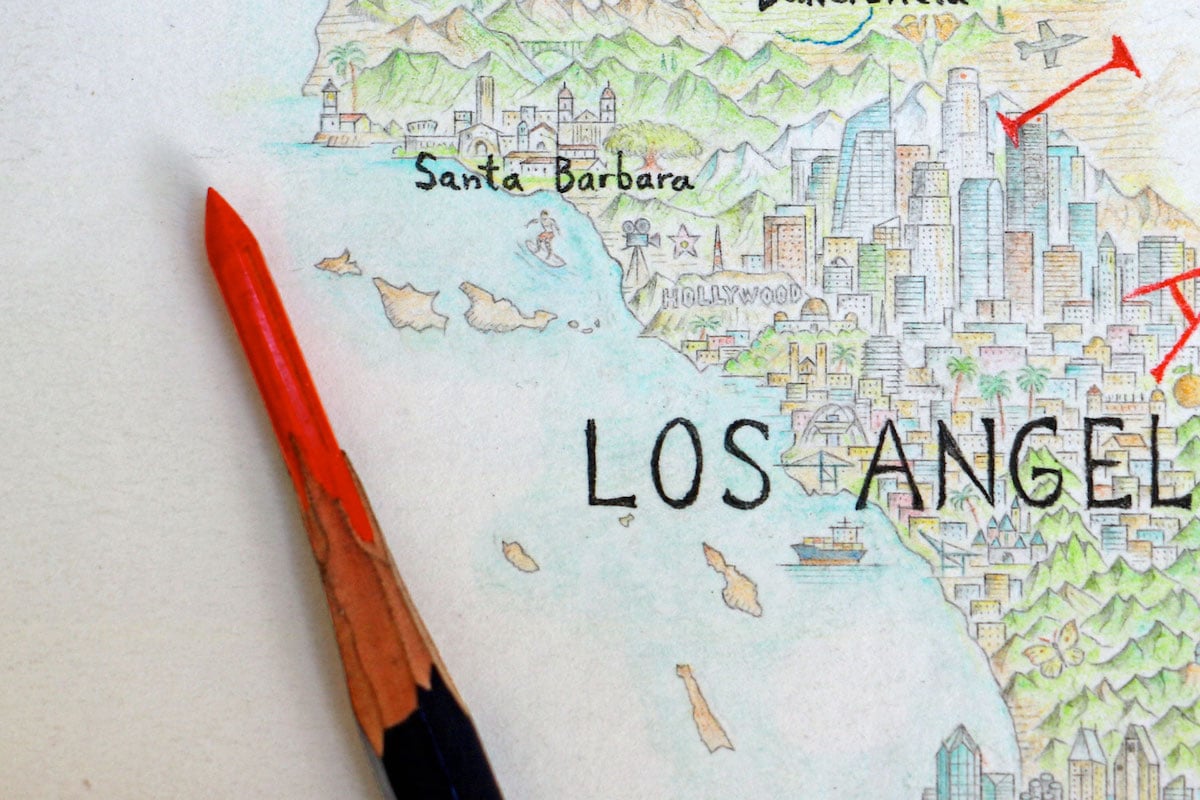

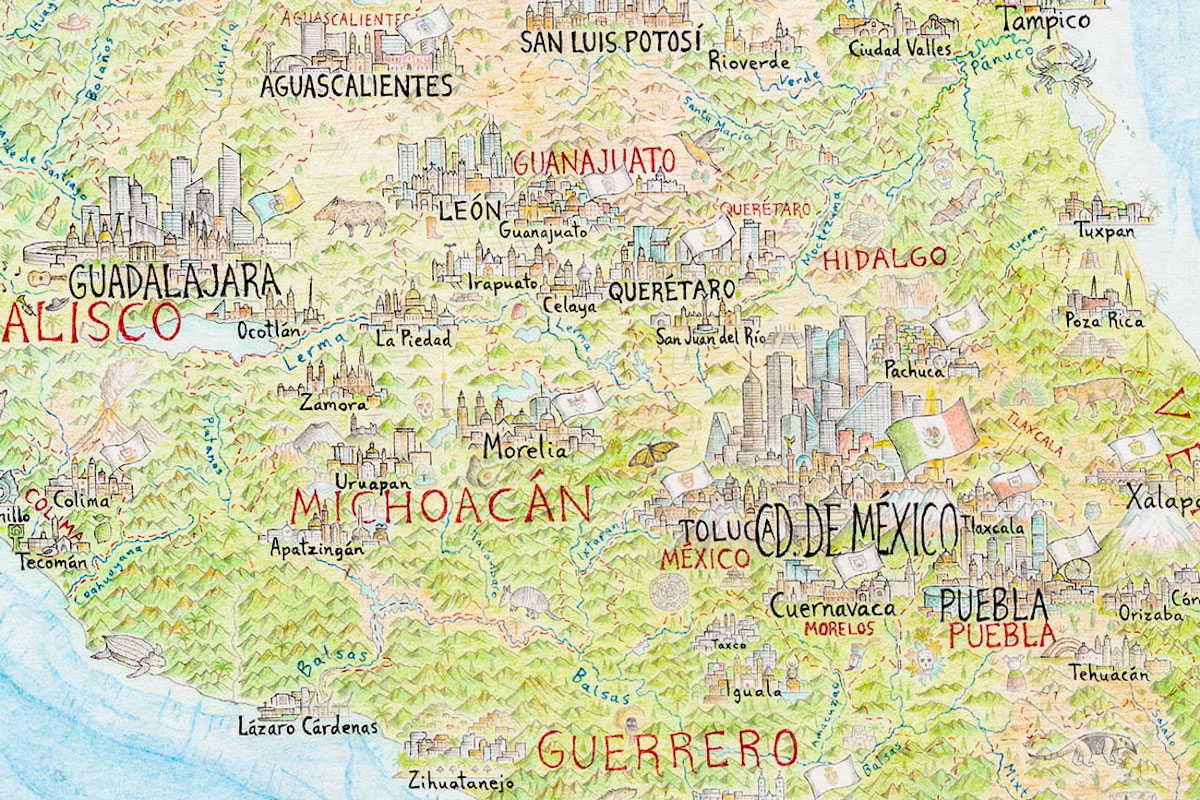

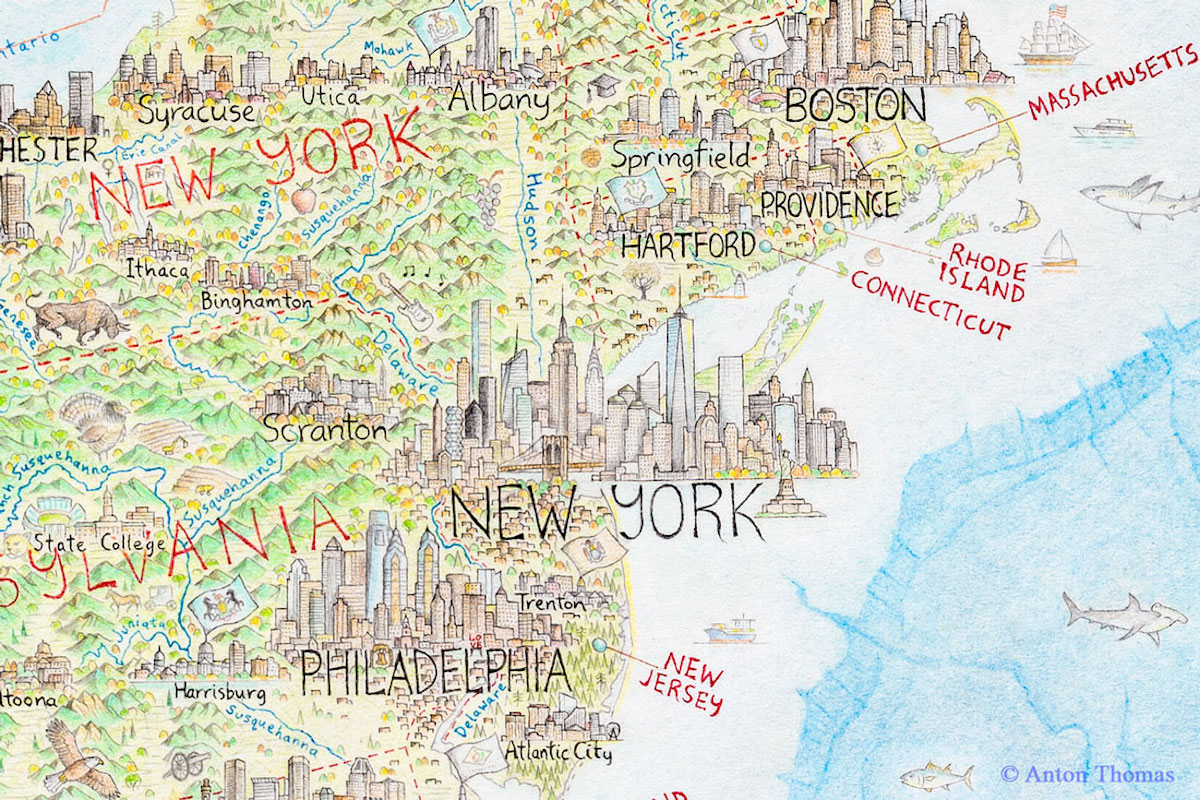

Artist and cartographer Anton Thomas is making waves for his enormous, hand-drawn map of North America. Executed in pen and colored pencil over the course of nearly 5 years, he spent almost 4,000 hours creating this incredibly detailed view of the continent. It's an ambitious project that required Thomas' dedication and a lot of sacrifice; but in the end, he was rewarded both personally and professionally for his trouble.

The 5′ x 4′ map sprawls across a single piece of paper and is a testament to Thomas' tenacity. No ordinary map, North America: Portrait of a Continent is filled with Easter eggs waiting to be discovered. This includes 600 individual city skylines, as well as thousands of details that help tell the story of an individual place. Whether it be local flora or fauna or emblematic symbols of a city or monument, Thomas has managed to draw just the right thing to set off every location.

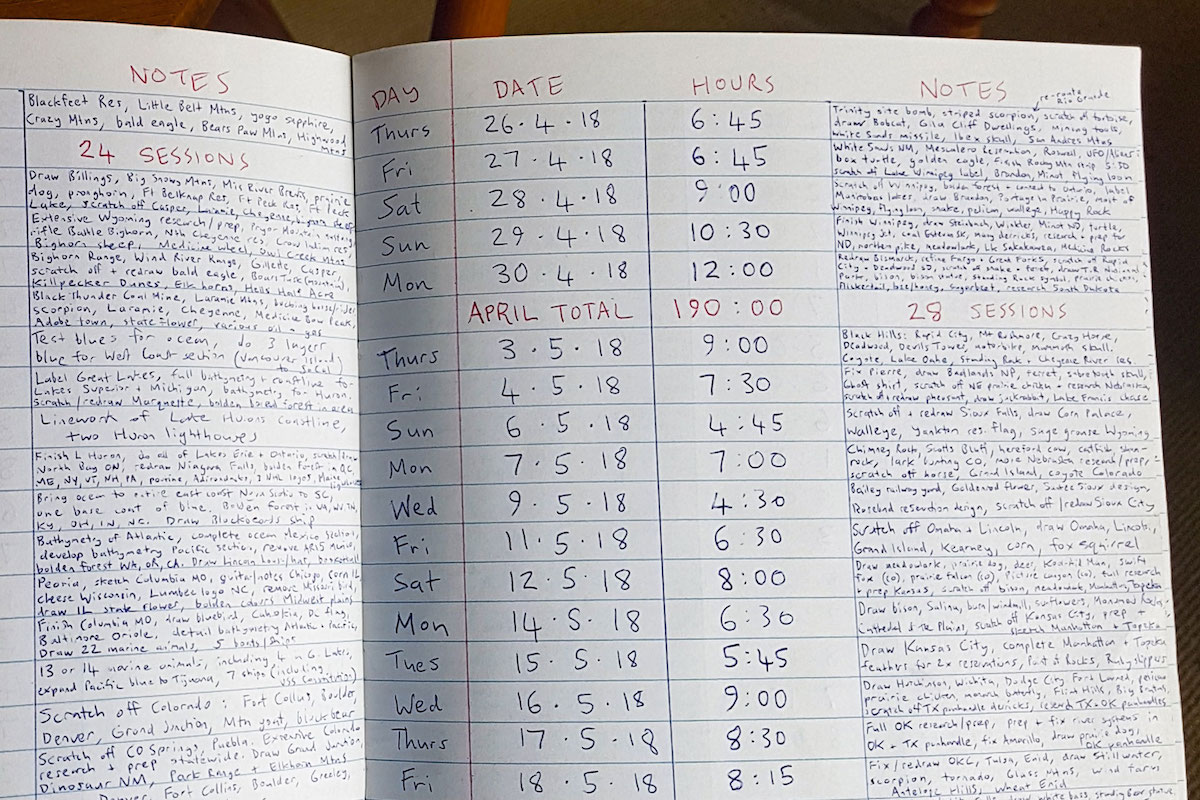

Thomas' project is made all the more impressive when one considers that he didn't leave his day job until the last year of the project, which means that his research and execution had to be incorporated into his off time. Such a long development period also meant that Thomas' drawing style changed over time. As he wracked up more hours working on the map, his skills sharpened. This refinement in his skills also meant that large portions of the map had to be erased and redrawn in order to make the finished product look uniform.

In the end, all of Thomas' efforts paid off. The completion of the map left Thomas time in 2019 to begin a side hustle giving talks about cartography and his map at schools, universities, and conferences. He was also able to execute some small illustrations for The Washington Post. And, best of all, he has been able to spread his love of cartography and let people around the world enjoy his map thanks to prints he sells on his website.

Want to learn more about this epic, hand-drawn map? Read on for My Modern Met’s exclusive interview with Thomas.

What was it about maps that captured your imagination as a child?

Growing up in New Zealand, it's not hard to be inspired by geography. The landscape is diverse and dramatically beautiful. I remember being captivated as a kid when I first took a flight between Nelson and Wellington. The places in my life were suddenly revealed from above as part of a grand theatre of geography, and maps helped me to understand this. I felt called to adventure by every page of an atlas, every road map in the glovebox of mum’s car, every bend of our coastline.

Your first major map-drawing experience was on a refrigerator. What did that experience teach you in preparation for your next map?

Drawing on that fridge in Montreal back in 2012 had a huge impact. It gave me the desire and confidence to pursue cartography further. While I drew maps constantly as a child, I ignored this passion as a teenager in exchange for playing guitar. That fridge was the first big drawing I’d done in years and it was so enjoyable, plus I could see myself improving each day. Meanwhile, friends were responding to the artwork in the most fascinating way. They would spend real time perusing it, pointing at it, using it to share stories about their lives. And it was clear why—I was drawing real places. Right there I got a taste of the power of mapping, that beating heart of cartography that makes it such an engaging artform: place.

Also, while drawing, I listened to more music and podcasts than ever before. This became one of my favorite aspects about being a visual artist; with the soundscape wide open you can listen to anything as you work. This has vast potential.

It took nearly 5 years to complete the North America map. How did the project change you as an artist—or as a person—during that time?

The map changed everything. It’s worth mentioning that during most of the project I had a day job, I only went full-time with my work in early 2018. This is a major reason that it took so long. I would get home, then draw at night, weekends, and holidays. The sheer scale of the task, all the hours alone, the sacrifice of my free time—at times I wondered if I was going mad. But I loved it. It was teaching me so much and I couldn't imagine giving up on what I’d started. It gave me thousands of hours of drawing experience and taught me considerable patience.

One of the biggest surprises from the map has been the number of spinoffs I didn’t expect. For example, I give a lot of talks now—from elementary schools to universities, conferences, and events around the world. I wouldn’t have guessed that drawing a huge map would lead to a passion for public speaking, which in turn has taken me in many new directions. From this to everything around the print release to all the music, podcasts, and audiobooks I enjoyed while drawing it, the map taught me more than I could’ve ever imagined.

What was the most challenging part of executing the North America map?

When I redrew a massive portion because my drawing had improved. By spending thousands of hours drawing on one piece of paper—that single original—a big inconsistency in quality opened between the older and newer stuff. This gulf became so significant that I opted to redraw a vast area (the western half of the U.S. and much of western Canada), which included scratching off huge amounts of the pen with an Exacto knife. Scraping the fine liner from the paper was a painfully slow, delicate process that I did not enjoy. It was the most grueling stage and it went on for over a year. Nonetheless, I’m glad I found a technique to execute this, as the map needed it. You can’t just leave an entire region subpar.

It was almost a year ago that it was completed. How has your life changed since that time?

It has changed so much. Until then, my life literally revolved around drawing it. In the weeks after completion, I didn’t even know who I was anymore, I felt I was trying to escape the orbit of a planet. As drawing the map demanded all my time, I’ve had a lot of business to catch up on since finishing. From image capture to printing, shipping, website building, e-commerce, marketing, general admin, and much more, it has been a big shift from the days of simply drawing a giant map.

No single demand now compares to the enormity of drawing it, but switching between these varying concerns has taken getting used to. Since finishing in February, I learned that yes, perhaps you can make your art your career, but that doesn't mean you always get to create all day. Sooner or later you'll have to manage your business, and 2019 taught me that in spades.

Do any areas of the map have special meaning to you?

There were many highlights, but I look back at Cuba especially fondly. Around this time I’d started listening to music to match the places I was drawing. Along with region-specific music, I'd watch movies, listen to podcasts, even go out for food and drink from the region—whatever I could do to feel I was tapping into a place. I was trying to treat mapping like a method actor.

This idea was first unlocked with Cuba. I became fascinated by the country when I watched Buena Vista Social Club, just before I started drawing it. I truly loved the music, and as I drew the island I cycled through a range of Cuban artists, far beyond only Buena Vista. That level of connection with the task was so fun—it enriched the map and my style—and I've explored the method mapping approach ever since. I even celebrated completing the country with a Cuban cigar. Drawing Cuba taught me new ways to feel engaged and inspired by the work.

The map is filled with so many details. What kind of research was involved in deciding what hidden gems would define different areas?

At the country, state, or city level, there’s so much research involved. I can’t just make things up. Whether it’s an elephant seal or a Mayan pyramid, there’s homework behind everything. It’s a tricky business as the world is vast and complex—any illustrated map of it is an extreme simplification.

Whatever the place, I read all I can to get a sense of its defining features. I’ll plan it out while trawling the internet—photos, maps, Wikipedia, travel sites, blogs, news, anything—approaching it as though I were planning to visit. Some things are iconic and easy choices (e.g. including the Statue of Liberty in NYC, Chichen Itza in the Yucatan), but at other times I could spend hours hunting for clues. Simply getting your bearings in the infinite lakes of the Canadian shield is hard, let alone determining how to represent such a region. Every place is different, so you have to be flexible as you go. Working on Miami is nothing like working on Nunavut.

While I can’t expect to please everybody—the maps are just my own interpretation of geography—cartographers have a role in defining places in the public mind. It’s important to take that responsibility seriously and treat all regions with respect. I’m not sure what it is to get it right exactly, but by choosing memorable things that would be familiar to a local, perhaps you get closer to something real. Our world is so astoundingly interesting that you’re never far from good options.

How is working on smaller illustrations, like the maps you did for The Washington Post, creatively different for you?

It’s hard to compare the North America map with anything else—the scale of work was extreme. Every state or province was like a new project. Even its cartouche (the title emblem) took longer to draw than the entire Washington Post set. Smaller projects are wonderful as they don't require some life-dominating commitment, and my efficiency and drawing ability is far higher than when North America started. Almost any project seems smaller in comparison, so I’m very excited to use all I’ve learned on new, manageable pieces. New ideas, new frontiers. There is so much to map.

What do you hope that people take away from your work and your story?

Everyone has their own experiences with my maps, and they take away different things. It’s always fascinating to hear what people have to say. I do hope to help inspire interest in geography and maps—and thus interest in the wider world. By presenting real places in this lively illustrated style, perhaps it will draw more people into maps. I’d like to encourage geographic literacy as much as I can; and with that, appreciation for our incredible planet.

As for my story: I hope to encourage people to follow their passion and creative instincts and to be patient and resilient in that journey. Don’t be afraid of making sacrifices for your art, especially early on. If you can carve out space in your life to get lost in your work, to devote the immense hours necessary to hone your craft, it will take you places you can’t predict. If you love creating something, then just do it—a lot. There’s no need to immediately worry about where it’s going.

I want people to know that it’s okay to lose yourself in the craft you love, to work at it obsessively, to feel consumed by it even. People around you may not understand, but don’t worry about what others think. Just create. If you’re deeply inspired by something that you’re investing real time in, that inspiration will flow out into the rest of your life.

What's next?

Nothing excites me more than considering what's next. For now, I’ll focus on smaller projects, starting with a small world map of animals I’ve been imagining for years. I also want to explore some ideas around mapping my home country of New Zealand.

That said, North America is subtitled Portrait of a Continent so that when I draw other continents, they’ll form a set. I’d love to draw South America: Portrait of a Continent, with the emerald sea of the Amazon sweeping up to the crest of the Andes, or Australia—where I live now—with its unique, ancient, technicolor geography. So while I have only smaller pieces in mind today, I know I'll draw the next continent even better (and faster) than North America.

Time log from the creation of the map.