Photo: Plombelec (CC BY-SA 4.0)

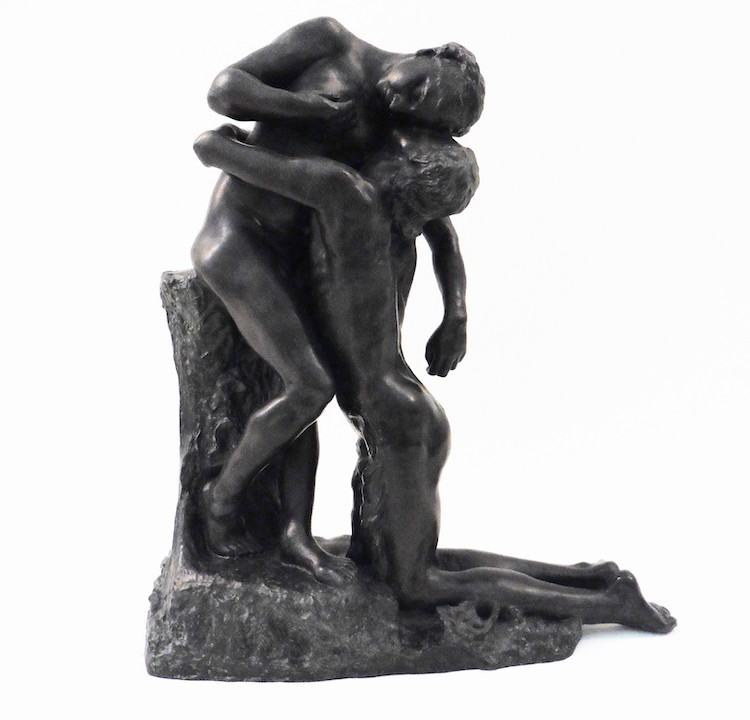

Throughout history, there have been many sculptors who have made a name for themselves. One is Auguste Rodin, the famous 19th-century French sculptor who created iconic pieces such as The Thinker, The Kiss, and The Gates of Hell. However, there are perhaps just as many artists who have gone unnoticed—particularly women. In fact, it is far less likely that you’ve heard of Camille Claudel, a female French sculptor who worked very closely with Rodin for a portion of her career. During their time of association, Claudel was Rodin’s student, assistant, muse, and lover. But more than that, she was an incredible sculptor in her own right—no easy feat for a woman during that period.

Still, despite the raw talent and drive that Claudel possessed, she—like many artists (especially female ones)—did not receive the success and acclaim she so desired and deserved during her lifetime. Though not entirely unknown and unsuccessful as an artist, her true importance was overshadowed by that of Rodin. Often confined by the rigid gender roles women were confined to and ultimately deserted by those she loved most, Claudel lived a tumultuous life that eventually came to a tragic and solitary end.

Though she died in almost complete insignificance, Claudel’s remarkable talent has since been rediscovered and celebrated to some degree. Read on to discover more about Camille Claudel’s fascinating life and career.

Early Childhood and Education

The oldest of three children, Claudel was born to a middle-class family in Fère-en-Tardenois—a small village in northern France—on December 8, 1864. Her father, Louis-Prosper Claudel, later moved the family to Bar-le-Duc In 1870. There, Camille received the beginnings of her education from the Sisters of the Christian Doctrine.

Claudel Children With Their Father, Right: Camille (Photo: Unidentified photographer [Public domain])

While Camille’s father was extremely supportive of her development as an artist, it was a completely different story with her mother. Louise Anthanaïse Claudel didn’t want her daughter to pursue a vocation as an artist. Aligned with the societal norms of the time, Louise viewed the profession as “unladylike” and preferred that her daughter give it up and focus more on her marriage prospects.

Arrival in Paris and Further Education

In 1881, Louis-Prosper Claudel moved his wife and three children to Paris so that their son—Paul Claudel—could pursue higher education. Then age 17, Camille took this opportunity to continue her artistic training and enrolled at the Académie Colarossi—an art academy that was extremely progressive for its time, not only accepting women to study there but also allowing them to work from nude male models.

Camille in Her Paris Studio (Photo: William Elborne [Public domain])

That same year, Boucher left Paris and moved to Florence, Italy. But before he left, he asked Rodin to take his place and continue to supervise and guide his pupils at the studio. It was there that Claudel and Rodin met, and that meeting marked a distinct shift that would completely alter the lives of both artists.

Camille Claudel and Auguste Rodin

Rodin was immediately impressed by Claudel’s work—though she was but a young student. The gritty realism apparent in her early works such as Old Helen struck him, and he soon invited her to work alongside him as an apprentice in his own studio. Claudel officially joined Rodin’s studio around 1883, by which time the seasoned sculptor had already received some of his first major commissions.

Bust of Rodin (Photo: Museo Soumaya [CC BY-SA 4.0])

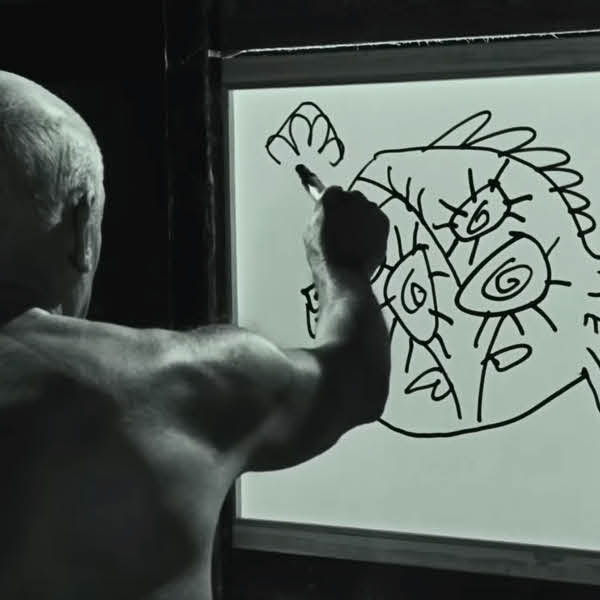

Nonetheless, Claudel and Rodin’s relationship was far from just a professional one. The two had mutual respect and admiration for one another and had become engaged in an impassioned love affair not long after they met. Even more than his apprentice, she became his confidant, model, and muse. Rodin created several portraits of Claudel during this period—starting with Camille Claudel with Short Hair—and also used her as a model for portions of his larger works. He, in turn, was also a model for Claudel on occasion, most notably for her acclaimed work Bust of Rodin. The two artists’ creations mutually inspired and influenced one another as they worked together seamlessly, sharing both models and studios.

Break From Rodin

Claudel and Rodin’s relationship continued for over 10 years, but things were not always so good. In fact, their romance had sparked a great deal of controversy—one reason being their sizable age gap, with Claudel not yet 20 when they first met and Rodin already into his 40s. One other reason was his relationship with Rose Beuret, who—though they were never officially married—had been his partner for years.

The Waltz (Photo: Camille Claudel [Public domain])

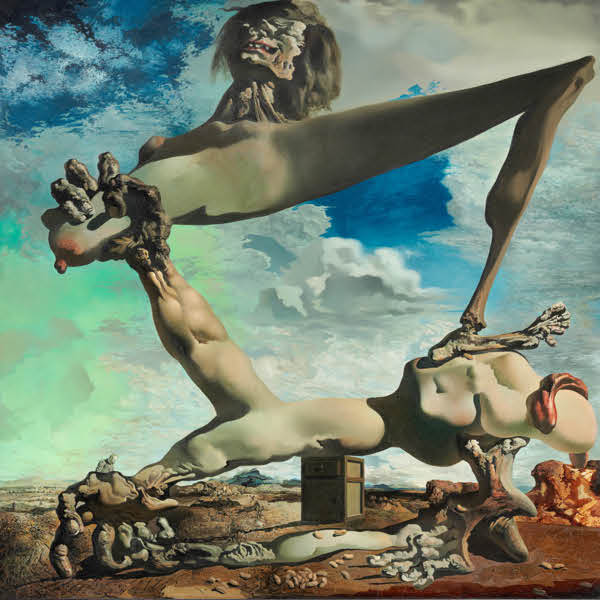

Though she had established and proved herself as an individual artist, people would always compare her to Rodin and attribute her talent and technique to the tutelage of the celebrated sculptor. Looking for a way to distinguish herself further from her former partner and assert her own creativity and genius, Claudel took a new direction with her work. She began to explore more intimate scenes, with more daring compositions, new subjects, and more difficult materials. Some of her most evocative and sensational work is from this period, including pieces such as The Waltz, The Wave, and Sakuntala.

The Wave (Photo: Thibsweb [Public domain])

Sakountala (Photo: Pierre André Leclercq [CC BY-SA 4.0])

The Age of Maturity (Photo: Thibsweb [Public domain])

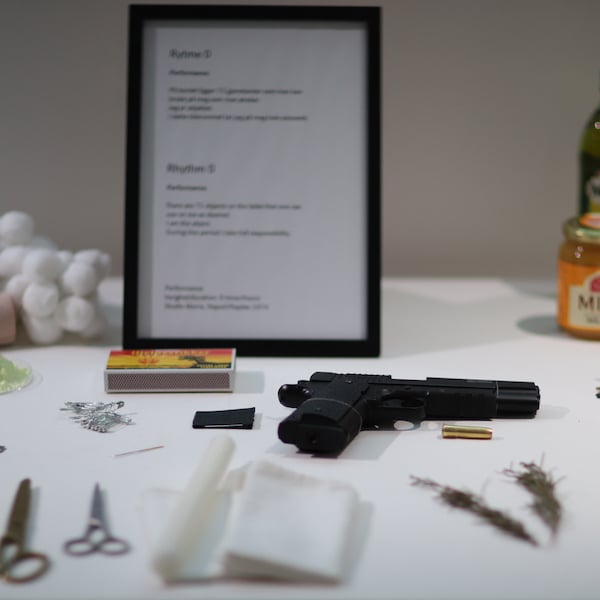

She had created this sculpture for her first commission from the French state in 1895, originally with the support and endorsement of Rodin. However, when he saw the sculpture for the first time, he was shocked, angry, and offended. He subsequently retracted his public support for Claudel’s work and severed all ties with his former lover. Her commission was also later revoked with little explanation, though many speculate that Rodin may have pushed the state to end its association with Claudel.

Claudel in 1903 (Photo: AnonymousUnknown author [CC BY-SA 4.0])

Tragic Final Years

After this final break with Rodin, things rapidly began to decline for Claudel. Though she had wanted to distance herself from the artist, his public support and endorsement of her work had protected her to some degree from many of the sexist practices evident in their artistic vocation. She increasingly lost support because of the overtly sensual nature of several of her pieces, which was not deemed acceptable for a female artist.

As her career rapidly declined and she fell into financial ruin, Claudel became increasingly paranoid and convinced that Rodin was plotting against her to ruin her and steal her ideas. Because of this, she became more and more reclusive, destroying a large portion of her pieces to prevent Rodin from copying them and even refusing to sculpt anything new. By 1911, she had become a shut-in, her physical and mental health continually worsening.

In March of 1913, her father—who had always supported and championed her—died, and no one from her family informed her. Claudel’s relationship with her mother, which had always been fraught from the moment the young girl decided to be an artist, had only deteriorated further and further over the years as her indecorous relationship with Rodin and the “unladylike” nature of her work only deepened the rift between Claudel and her mother.

Bust of Paul Claudel at 37 (Photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra from Paris, France [CC BY 2.0])

She was later transferred to Montdevergues asylum in 1914—due to the outbreak of WWI—and remained there until her death on October 19, 1943. Over the course of her 30-year confinement, she received very few visits from her family or friends. Claudel spent the rest of her days in isolation, removed from all the things that had once made her life vibrant.

“I have fallen into an abyss,” the artist wrote to one of her few remaining contacts during her time at Montdevergues. “I live in a world so curious, so strange. Of the dream that was my life, this is the nightmare.” After Claudel’s lonely death, her body was buried in an unmarked communal grave on the asylum grounds.

Camille Claudel’s Legacy

In spite of the unjust decline of her sculpting career as well as her life’s tragic ending, the world has once again started to take notice of the work of Claudel. So compelling is her story that it has even been the inspiration for books, plays, films, and even a musical. Before his own death in 1914, Rodin approved plans to add a Camille Claudel room to his museum. These plans were completed in 1952 when Claudel’s brother, Paul, donated several of his sister’s works to the Musée Rodin.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public domain]