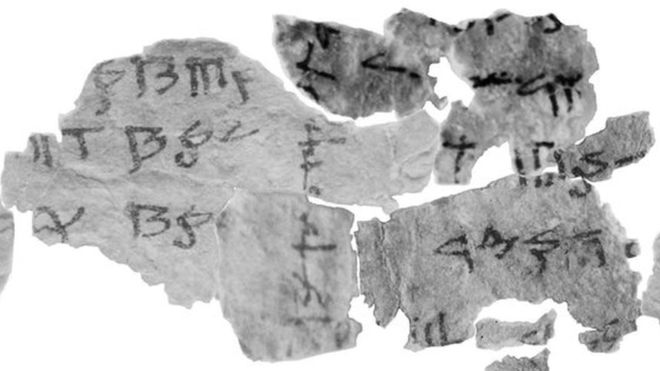

Photo: University of Haifa

Researchers have deciphered one of last remaining Dead Sea Scrolls from over 900 that were originally found in the Qumran Caves more than 60 years ago. Since their discovery, these ancient religious texts—which date to at least the 4th-century BCE—have shed new light on how the Jewish religion was practiced and include the oldest known manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible.

Now, Dr. Eshbal Ratson and Prof. Jonathan Ben-Dov of the Department of Bible Studies at the University of Haifa have restored and deciphered one of last two scrolls that had remained unpublished. This came after testing helped them discover that small fragments thought to belong to numerous different scrolls were, in fact, from one document. The Israeli researchers then spent more than a year painstakingly piecing together more than 60 fragments—some smaller than 1 square centimeter (0.155 square inches)—in order to reveal the ancient code.

What they found were references to a 364-day calendar, unique to the desert sect that would have written the scrolls, and several important festivals that are not mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. Referred to as the festivals of New Wine and New Oil, they helped herald the changing of seasons and were an extension of what is now known as Shavuot. This discovery is important, as until now researchers were aware of the festivals but did not know the names for these celebrations.

The Dead Sea Scrolls were first discovered in the Qumran Caves, which are located in the Judaean Desert of the West Bank. (Photo: Dennis Jarvis)

The authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls remain a mystery, though experts have traditionally attributed them to a desert sect called the Essenes. The work of the University of Haifa researchers provides interesting insight into the authors of the scrolls—including their mistakes. It appears that one scribe forgot to include several noteworthy dates, leaving a second scribe to correct the oversite with annotations in the margins.

“The scroll is written in code, but its actual content is simple and well-known, and there was no reason to conceal it,” the researchers explain. “This practice is also found in many places outside the Land of Israel, where leaders write in secret code even when discussing universally-known matters, as a reflection of their status. The custom was intended to show that the author was familiar with the code, while others were not. However, this present scroll shows that the author made a number of mistakes.”

Interestingly, these mistakes are what assisted the researchers in solving the puzzle. Dr. Ratzon spoke to Haaretz, Israeli's longest-running newspaper, admitting: “What's nice is that these comments were hints that helped me figure out the puzzle—they showed me how to assemble the scroll.”

h/t: [Mental Floss, BBC]

Related Articles:

3,500-Year-Old Stone Carving Discovery May Change Art History as We Know It

4,000-Year-Old Assyrian Tablet Discovered Is an Ancient Prenuptial Agreement

Scholars Decipher 3,200-Year-Old Hieroglyphic Inscription

Researchers Crack Mathematical Code of 3,700-Year-Old Babylonian Tablet