Lion

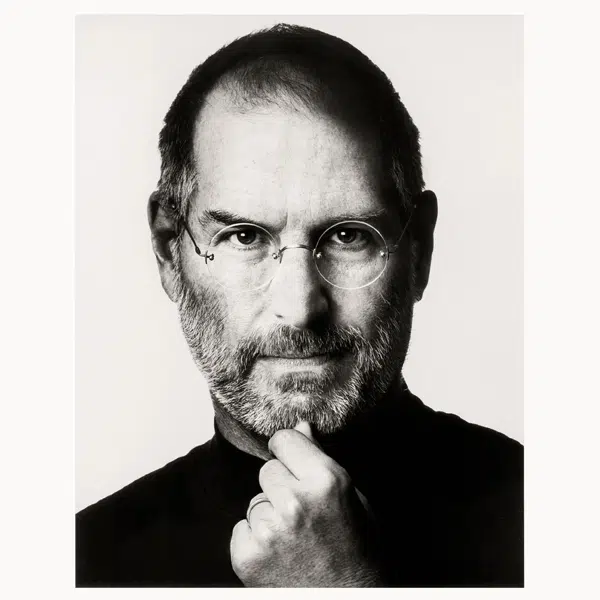

With an emphasis on showcasing the “brilliance, beauty, and fragility of the natural world,” British photographer George Wheelhouse specializes in striking depictions of wildlife. In his twin series, On Black and On White, Wheelhouse employs extreme lighting and creative in-camera techniques to capture revealing portraits of animals.

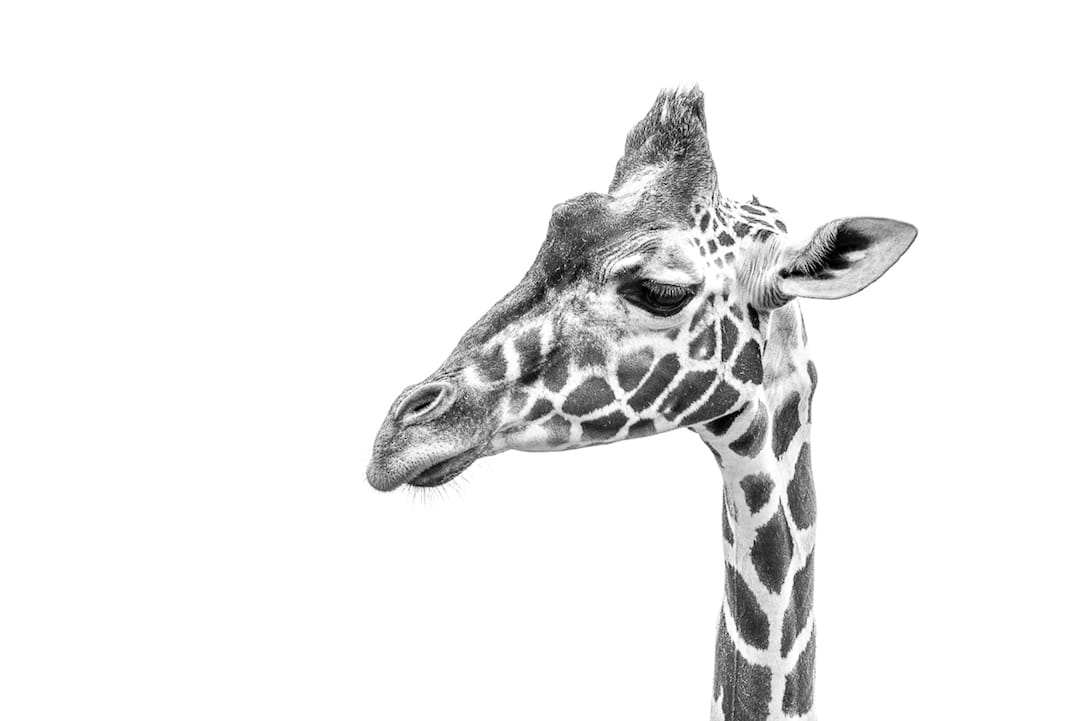

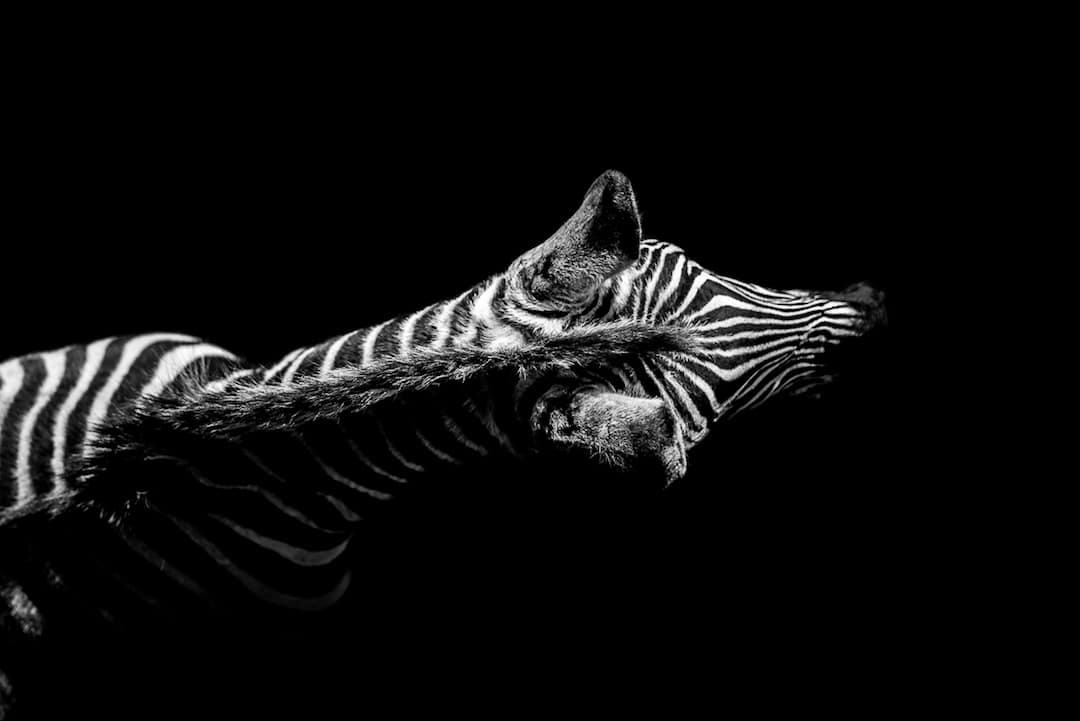

Each creature featured in On Black and On White is artistically illuminated against a stark backdrop. While their captivating compositions and subjects are similar, the drastically different lighting of each series culminates in contrasting moods. Where On Black‘s darkness evokes drama, On White‘s illumination suggests optimism—an attitude that is particularly potent during this dire time for nature.

In addition to creating eye-catching art, Wheelhouse employs this distinctive aesthetic to humanize his subjects, which range from native fauna to animals housed in zoos and wildlife centers. “It's a style of photography evolving from conventional, human portrait photography, and I like to recreate that feeling of the subject ‘sitting' for the portrait and actively engaging with the viewer,” he tells My Modern Met. “I want to convey the character of the individual I'm photographing, to spark a connection and empathy with the viewer. My ultimate goal is to highlight the similarity between humanity and nature, and reinforce a respect for animals.”

We recently had the opportunity to talk to Wheelhouse about his incredible On Black and On White series. Below, he discusses the inspiration and process behind this meaningful project and speaks about his fascinating practice in general.

Giraffe

What led you to pursue nature and wildlife photography?

I’ve always enjoyed creative things: drawing, design, and woodcraft. I used to draw a lot when I was younger, always animals, often using photos as a source. Once I discovered photography, I could go out and take the photos I wanted—so it offered a kind of freedom in that respect.

I soon realized that I was better at photography than drawing, but my artistic background had provided me with a lot of crossover skills such as composition, understanding of light, etc. Probably most importantly to me, nature photography offered a therapeutic escape from the hustle and bustle of day-to-day life, as well as a creative outlet.

Puffin

For your series, On Black and On White, you photograph animals against stark backdrops. What is the inspiration behind this approach?

I think there are two main approaches to photographing animals. One is to depict them in their environment; documentary-style. The other is to portray them as individuals and characters.

I dabble in classic wildlife photography now and again, but it’s really the portraits which interest me most. And I figured that the best way to communicate the character of an animal is to borrow techniques from portrait photographers and painters. They traditionally use plain backdrops to avoid distractions from the subject. I’m attracted to the minimalism of the low-key portrait style; only revealing what’s necessary, and leaving the rest for interpretation. I also think there’s something about the darkness which interests me. It creates a sense of visual drama and encourages empathy for the subject, but metaphorically it represents kind of a dark time for wildlife and nature in general.

The high-key portraits came about later, as I was out photographing deer and found completely the opposite lighting conditions for the low-key photo I wanted. I tried a high-key version instead and it worked really well. I then realised that the two projects would complement each other really well, like yin and yang, with the high-key offering a more optimistic feel, with their bright, graphic appearance. The two styles reflect the two sides of my character too, as my disposition is generally fairly polarized.

Puffin

How do you decide which animals to feature?

Sometimes it’s a case of being out and encountering an animal in the right light and conditions, but most often it’s a shot that I’ve planned and prepared for. I like to photograph species which I think have a relatable quality to them, as this is a key aspect of a portrait. Also animals which are unusual, or often overlooked. My images frequently portray animals with antlers and horns, as I think they add something interesting visually.

Once I have a species in mind, I consider whether they’ll suit a high-key or low-key aesthetic. Some animals can work equally well in both styles, but others just “feel” more one than the other to me.

Red Deer

How do you gain access to the animals you photograph?

Most often, I photograph animals which are available via public access, such as deer parks and farmland. This means I can visit when I want—which is generally sunrise or sunset, and I can visit multiple times. Since I’m working with animals and natural light, it can take several visits to achieve the shot I have in mind. I live near a deer park with public access, so I take a lot of deer photos, and they always make for an interesting subject. I think cows are fabulously photogenic, so they’re enjoyable subjects too. They often appear to have a ponderous expression to them.

I take photos of wildlife too, both here in the UK and abroad. The more exotic species I’ve photographed have been in zoos and wildlife centers, which provide a great opportunity to practice with species which are hard to find in the wild. But you really have to be flexible there, and work with the light and the enclosures, so it can be tough to get something pre-planned.

Cow

Can you explain the process behind photographing the animals?

It’s not a technically difficult method, but it requires some creativity, and some experience and understanding of light— again, things which I was fortunate to learn before I came to photography. For low-key images I look for strong low sunlight, and areas of shadow for the background. By exposing for the highlights, the comparatively limited dynamic range of the camera exaggerates the darkness of the shadows. High-key images require the opposite situation, where the background is strongly lit, but the subject is back-lit or un-lit. Then by exposing for the subject, the highlights are rendered white by the camera.

Using only the sun for light and an animal as a subject means that I often don’t have everything perfect in-camera. I spend some time cleaning the digital images up, and ensuring that the light is even, and they show as much or as little of the subject as I want. Some come out as I’d like with minimal processing, and others require a bit of work to ensure that the background is completely obscured, and the light is illuminating the subject as I intended.

Zebra

What challenges have On Black and On White presented?

Firstly, in a technical respect, when I started out experimenting with the processing method, I was using Photoshop, but I never felt happy with it. When I discovered Lightroom, its non-destructive workflow really appealed to me, and I think the way in which you can locally adjust areas of exposure creates a much more realistic result.

My confidence in my photography has wavered at times, but that has encouraged me to become more critical of my work, more selective of subjects, and leads to higher quality images—if fewer of them. I'm an introvert, so it can be hard to put myself out there. But I want to share my work, and hopefully inspire others to follow their creativity too.

Red Deer

Do you have any particularly memorable shoots or favorite photos from these series?

I had wanted to photograph a Swaledale sheep for a few years, as I knew that their characteristic curled horns would look great fading in and out of the black. They’re an iconic breed, and the logo of the Yorkshire Dales National Park. I’d even visited Swaledale in the Yorkshire Dales, and walked through fields of them—but I didn’t encounter one with large horns in that time.

Then, last year I was out at sunrise, photographing landscapes in the Peak District National Park, and on the way back to the car I chanced across a grand old Swaledale sheep, who posed very patiently for me. In fact I was able to take both low-key and high-key photos, as it moved in and out of the shade of a large oak tree. I had always wanted a low-key portrait of a Swaledale, and I’m really proud of that photo, but in fact the high-key came out well too, and a lot of people prefer that one. Again, I like the fact that they each have a very different feel, with the brighter image showing a more positive view, compared to the dark and moody feel of the portrait on black.

Swaldale Sheep (On Black)

Swaledale Sheep (On White)

In addition to animal portraits, what other photographs do you enjoy taking?

I love to travel, and I enjoy landscape photography as well as wildlife photography. I’m especially fond of cold environments. I’ve just returned from Abisko, in the Swedish Arctic, where I was photographing snow-capped mountains and aurora.

I’m also very drawn to trees and woodlands. I have an on-going landscape photography project called Only Trees, intended to be the antithesis of the popular “lonely tree” trope, as I fill the frame with large areas of forest to create an abstract-style texture of woodland.

Highland Cow

Lastly, do you have any upcoming projects or plans?

This year I’d really like to photograph more highland cattle. They’re a very placid breed, with a calm temperament, and visually they have a lot going on. Once again, I think the horns add something visually engaging, as well as adding to the character of the subject. Often you can’t even see their eyes under their long curly hair, so it’s an enjoyable challenge to create a relatable portrait of a creature without even using eye contact.

Griffon Vulture

See more of George Wheelhouse's stunning animal portraits below.

Moose

White-Tailed Sea Eagle

Bengal Tiger