Photo: Stock Photos from ArtSyslik/Shutterstock

As one of the world's most walkable cities, Paris makes wandering around an ideal way to experience life in the French capital. As you stroll along its streets, you'll encounter all kinds of eye-catching sites, like its world-famous metro entrances, one-of-a-kind storefronts, and, towering above the rest, its historic Haussmann apartment buildings.

Designed by Baron Georges Eugène Haussmann as a means to modernize 19th-century Paris, these buildings have since become a symbol of the city's traditional charm. While any visitor to Paris's busiest boulevards is sure to spot these cream-colored flats, many are probably unaware of their history—and the controversial origins of their now-celebrated legacy.

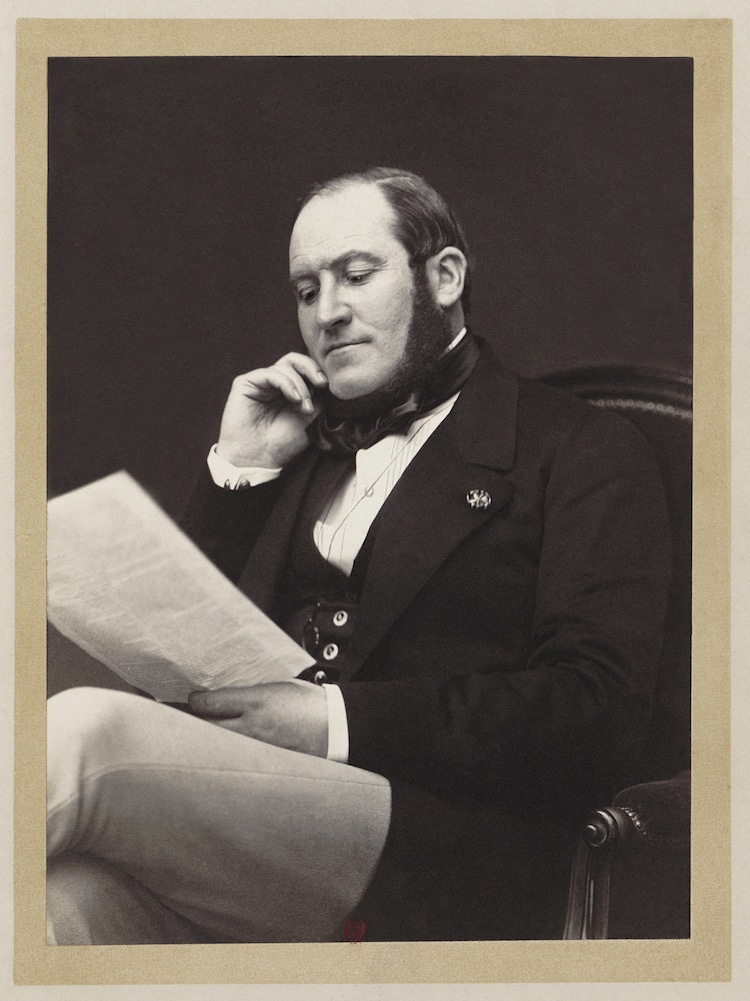

Baron Haussmann and the Reconstruction of Paris

Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Georges Eugène Haussmann was born in Paris in 1809. In his early 20s, he entered the realm of public administration, serving as the secretary-general of a prefecture in southwestern France. Following this role, he was appointed to a series of increasingly important posts around the country.

In 1848, when Haussmann was working as a deputy prefect of another southwestern department, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoleon I, was made President of France. Following in the footsteps of his uncle, he would eventually seize power in order to become Emperor. During his 18-year reign as Napoléon III, the name he adopted as supreme leader, one of his major undertakings involved the complete reconstruction of Paris.

By the middle of the 19th century, the city could no longer support the health, transportation, and housing needs of its growing population. To remedy this major problem, Napoléon III appointed Haussmann as the prefect of the Seine, a role that required him to oversee an ambitious series of public works projects. From 1853 until 1870, Haussmann outfitted the city with new water and sewers, train stations, and, most famously, a network of uniform boulevards. It was a total transformation of Paris into a modern metropolis.

The Boulevards of Paris

Camille Pissarro, “Boulevard Montmartre,” 1897 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Haussmann was chosen by the Emperor to lead the design and construction of this network of boulevards. Napoleon III hoped that these wide, open roads would “aérer, unifier, et embellir” (“air, unify, and beautify”) Paris, which was still primarily made up of dark, medieval alleys and winding passages. Though historic, Haussmann opted to demolish many of these narrow streets, culminating in a controversial event he would eventually be described as the “gutting of old Paris.”

The Rue du Jardinet on the Left Bank, demolished by Haussmann to make room for the Boulevard Saint Germain, ca. 1853–1870 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

In 1859, Haussmann completed the grande croisée de Paris, a project that introduced a major intersection to the center of the city. In addition to modernizing the rue de Rivoli, rue Saint-Antoine, Boulevard de Strasbourg, and Boulevard Sébastopol—all of which remain widely-used thoroughfares today—the construction of this “grand cross” culminated in the redesign of several sites in Paris. These include the Place du Carrousel, a public square adjacent to the Louvre; the areas surrounding Hôtel de Ville, Paris' city hall; Les Halles, the central marketplace; and the Place du Châtelet, a bustling plaza at the center of this new axis.

After constructing the grande croisée de Paris, Haussmann continued to build boulevard after boulevard all throughout Paris. This urban planning resulted in a network of wide, open streets and tree-lined avenues. On top of their spaciousness, there is an architectural element that makes Haussmann's boulevards instantly recognizable: their apartment buildings.

Haussmann Buildings

Photo: Stock Photos from Pascale Gueret/Shutterstock

To line his boulevards, Haussmann designed and developed a new kind of living space. Unlike the narrow, mismatched flats of medieval Paris, his modern apartment buildings would have uniform exteriors, culminating in cohesive blocks that further emphasized Napoleon III's idea of a “unified” Paris.

Characteristics

While the interiors of these apartments can differ from building to building, Haussmann declared that their façades must follow strict guidelines. All apartments are made from a cream-colored stone, with the locally sourced Lutetian limestone among the most prevalent. Though their heights range from 12 to 20 meters tall (39 to 66 feet tall), each building is proportional to the boulevard and does not exceed six stories. They also have steeply sloped, four-sided mansard roofs angled at 45°. Finally, the flats' façades are all stylistically similar, according to a general floor-by-floor plan.

Floor by Floor

Photo: Stock Photos from sylv1rob1/Shutterstock

Though exact designs vary, most Haussmann buildings follow a standard layout:

- The ground floor has the highest ceilings as well as thick walls to accommodate shops, offices, and other businesses.

- The first floor, known as the “mezzanine,” has low ceilings and is typically used by businesses for storage.

- The second floor, or “noble floor,” is traditionally a building's most desirable flat, as it requires the shortest climb on the stairs. The second floor has a long, running balcony and beautifully crafted window frames.

- The third (and sometimes fourth and fifth floors) have smaller balconies and less elaborate windows.

- To add balance to the building, the top floor also features a large, running balcony. However, as this level is not “noble,” the balcony is not intricately decorated and the windows are identical to those found on the third and fourth floors.

- The building is then topped with the mansard roof, which houses small attic rooms (traditionally used as servants' quarters) and dormer windows.

Haussmann's Legacy

Photo: Stock Photos from jooh/Shutterstock

In the late 1860s—less than 10 years after introducing the Haussmann building—Haussmann was facing increasing criticism. On top of complaints about his complete disregard for “old Paris,” residents were concerned about the costs of his projects, which, ultimately, came out to 2.5 billion Francs. There were also mounting suspicions that Napoleon III ordered big boulevards not to “air, unify, and beautify” Paris, but to accommodate his large-scale army and fit troops marching down the streets of Paris.

Above all else, as Haussmann notes in his memoir, Parisians were bothered by the city's constant construction—and the fact that Haussmann was allowed to implement such a lengthy undertaking. “In the eyes of the Parisians, who like routine in things but are changeable when it comes to people, I committed two great wrongs: Over the course of 17 years, I disturbed their daily habits by turning Paris upside down, and they had to look at the same face of the Prefect in the Hotel de Ville,” he says. “These were two unforgivable complaints.”

Due to mounting opposition against him, Haussmann was ultimately dismissed by Napoleon in 1870. Afterward, France fell into the Franco-Prussian War, leading to Napoleon III's capture and the Empire's end. Years later, the new prefect of the Seine, Jean-Charles Adolphe Alphand followed in Haussmann's footsteps by finishing the rest of the renovation projects, including the Paris Opéra (1875), the Avenue de la République, and finally, the Boulevard Haussmann (1927).

Even with such controversy, however, Haussmann's renovations immediately improved the city's quality of life. The infrastructure change brought open air, more public parks, and clean water to the city of Paris. Today, both Haussmann and his designs are celebrated, with the popularity of Boulevard Haussmann—a famous street that features his iconic apartment buildings—perpetually setting his legacy in stone.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

Paper Haussmann Buildings Capture the Charming Details of Parisian Architecture