New York City has always attracted avant-garde artists. From the energetic Abstract Expressionists to the pioneers of American Pop Art, forward-thinking creatives have flocked to the city that never sleeps for decades. While each and every modern movement cultivated in the Big Apple has made its mark on the history of art, the Harlem Renaissance enabled an entire population to flourish.

Throughout the 1920s and into the 30s, New York City's Harlem neighborhood thrived as a cultural hub for African Americans. During this “golden age,” the arts thrived, culminating in a cultural movement that saw the creation of one of modern art's most moving works: The Migration Series, a prolific collection of paintings by African American artist Jacob Lawrence.

The Inspiration Behind The Migration Series

Completed in 1941, The Migration Series colorfully tells the story of the Great Migration—a mass exodus of over 6 million African Americans from the South. Fleeing economic hardship and laws shaped by segregation, these individuals relocated to urban areas in the West, Midwest, and—most prominently—the North. In these new cities, the migrants mostly stuck together, forming supportive communities by settling into neighborhoods like Harlem.

“The Harlem section of Manhattan, which covers just three square miles, drew nearly 175,000 African Americans, giving the neighborhood the largest concentration of black people in the world,” the National Museum of African American History and Culture explains. “Harlem became a destination for African Americans of all backgrounds. From unskilled laborers to an educated middle-class, they shared common experiences of slavery, emancipation, and racial oppression, as well as a determination to forge a new identity as free people.”

Lawrence's Early Life and Career

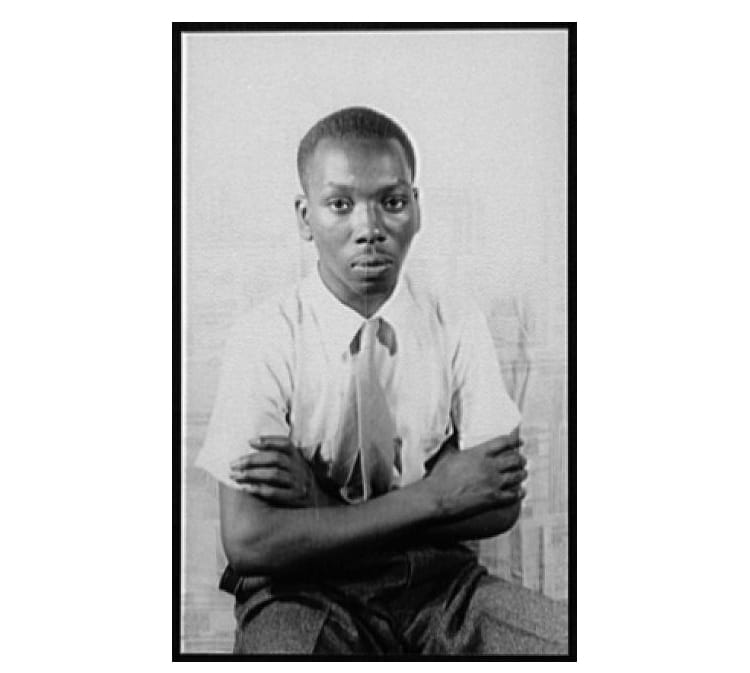

Carl Van Vechten, “Portrait of Jacob Lawrence,” 1941 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

It is no surprise that Lawrence found inspiration in the Great Migration. Born in Atlantic City in 1917 to Southern-born parents (his mother was from Virginia; his father was from South Carolina), Lawrence's own family had relocated to New Jersey during the Great Migration. When he was a child, his parents divorced. Though he and his siblings ended up in foster care in Philadelphia, they were able to reunite with their mother in Harlem in New York City in 1930 when Lawrence was 13 years old.

At this time, the Harlem Renaissance was in full swing. A budding artist, Lawrence honed his skills with art classes at Utopia Children's Center and, eventually, the Harlem Community Art Center, a studio space established through the Federal Art Project. Most importantly, his creative side was supported by his surroundings. These organic influences include his mother's colorful taste in home furnishings (“Our homes were very decorative, full of pattern, like inexpensive throw rugs . . .” he said, “I got ideas from them, the arabesques, the movement and so on.”) and the African American hub he called home. “The community [in Harlem] let me develop,” he reflected. “I painted the only way I knew how to paint . . . I tried to put the images down the way I related to the community.”

On the heels of a celebrated collection of narrative portraits of Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and other figures in Black history, this community-fostered approach proved successful for Lawrence when, at just 23 years old, he garnered national attention with The Migration Series.

The Migration Series

The Migration Series (originally titled The Migration of the Negro) comprises 60 paintings that, together, tell the story of the Great Migration. Each scene is rendered in tempera paint on a cardboard panel, and is executed in Lawrence's signature style: simplistic compositions, stylized forms, and vivid colors. In order to ensure a cohesive flow of tone and style, Lawrence painted each panel in a series of simultaneous steps.

When paired with the historic subject matter (which spans bustling train stations full of black passengers to abandoned, flooded farms), this aesthetic approach presents the Great Migration through a novel lens. “Lawrence’s work is a landmark in the history of modern art and a key example of the way that history painting was radically reimagined in the modern era,” the Museum of Modern Art explains.

In order to tell this important story as clearly as possible, Lawrence paired each panel with a caption. The series' opening line, for example sets the scene: During World War I there was a great migration north by southern African Americans. Throughout the course of the collection, Lawrence explains a range of other events and experiences—from the importance of the black press (panel 20) to the “more educational opportunities” (panel 58) offered by the North—until panel 60 concludes the series with an open-ended statement: “And the migrants kept coming.”

After The Migration

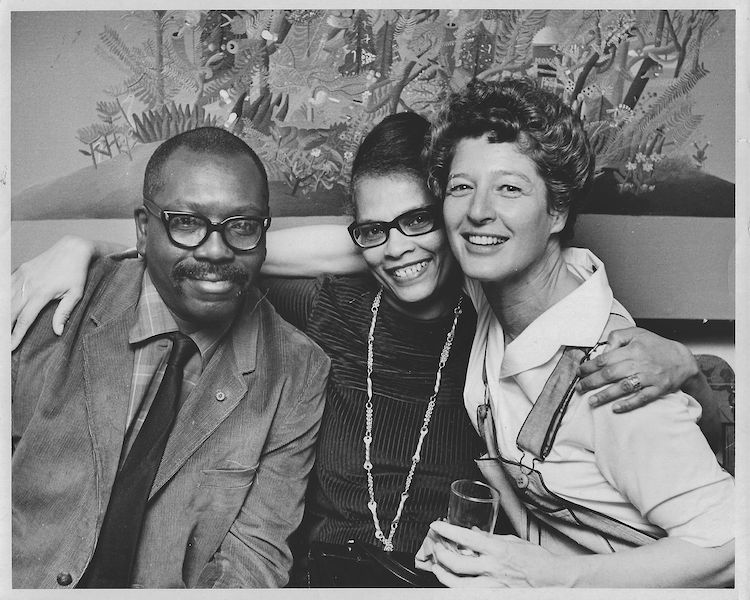

Art dealer Terry Dintenfass with Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence, ca 1970 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In 1941, The Migration Series was exhibited for the first time at the Downtown Gallery in Manhattan, where it attracted two interested parties: the Phillips Collection in Washington DC and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City. Illustrating the importance of the series, neither buyer budged; finally, they decided to split the collection, with the Phillips Collection acquiring the odd-numbered panels and MoMA receiving the even-numbered ones.

After the success of The Migration Series, Lawrence launched a career as a teacher. He worked at several universities, including the University of Washington, where he taught for sixteen years. He also continued to create art until his death in 2000, completing powerful works that carry the legacy of The Migration Series.

“To me, migration means movement,” Lawrence said. “There was conflict and struggle. But out of the struggle came a kind of power and even beauty. ‘And the migrants kept coming' is a refrain of triumph over adversity. If it rings true for you today, then it must still strike a chord in our American experience.”

Related Articles:

Norman Rockwell’s “The Problem We All Live With,” a Groundbreaking Civil Rights Painting

Striking Street Photos Capture the Vibrant Culture of Harlem in the 1970s

Colorful Quilts Crafted from African Fabrics Tell Stories of Artist’s Ancestral Homeland

New York Subway Murals Celebrate Influential Icons from Bronx History