Jacques Louis David, “The Death of Socrates,” 1787 (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Public Domain)

In the middle of the 18th century, several styles dominated Europe's artistic tastes. In France, the frivolous Rococo genre was taking shape, and Baroque art was well-established across the continent. While both of these popular periods can be characterized by an interest in extravagance, not all 18th-century art shared this sentiment. In fact, Neoclassical artists like Jacques-Louis David had the opposite approach to painting, as typified by his subdued masterpiece, The Death of Socrates.

The Death of Socrates Painting

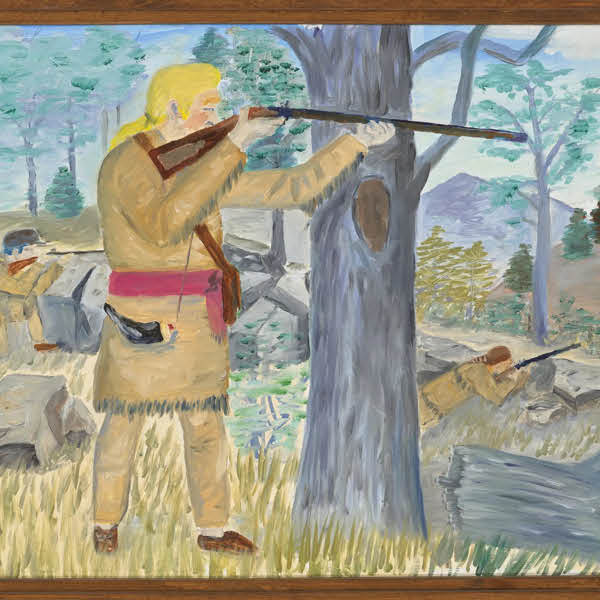

The Death of Socrates is one of the most well-known works of art to come out of the Neoclassic period. In the 1780s, French artist Jacques-Louis David began producing pieces that showcased an interest in classical themes and aesthetic austerity. He completed The Death of Socrates at the height of this phase in 1787, and submitted it to the Paris salon that year.

The Paris salon was an annual exhibition organized by the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts. As the academy had a traditional approach to art, realistically-rendered paintings of historical, mythological, and allegorical scenes were favored, making David's piece an instant hit.

Comparing it to the Sistine Chapel's ceiling by Michelangelo and the Stanza della Segnatura frescos by Raphael, critics praised the painting. In particular, it was favored for its classical subject matter, harmonious composition, and precise draughtsmanship—three qualities that characterize Neoclassicism.

Neoclassical Characteristics

Classical Subject Matter

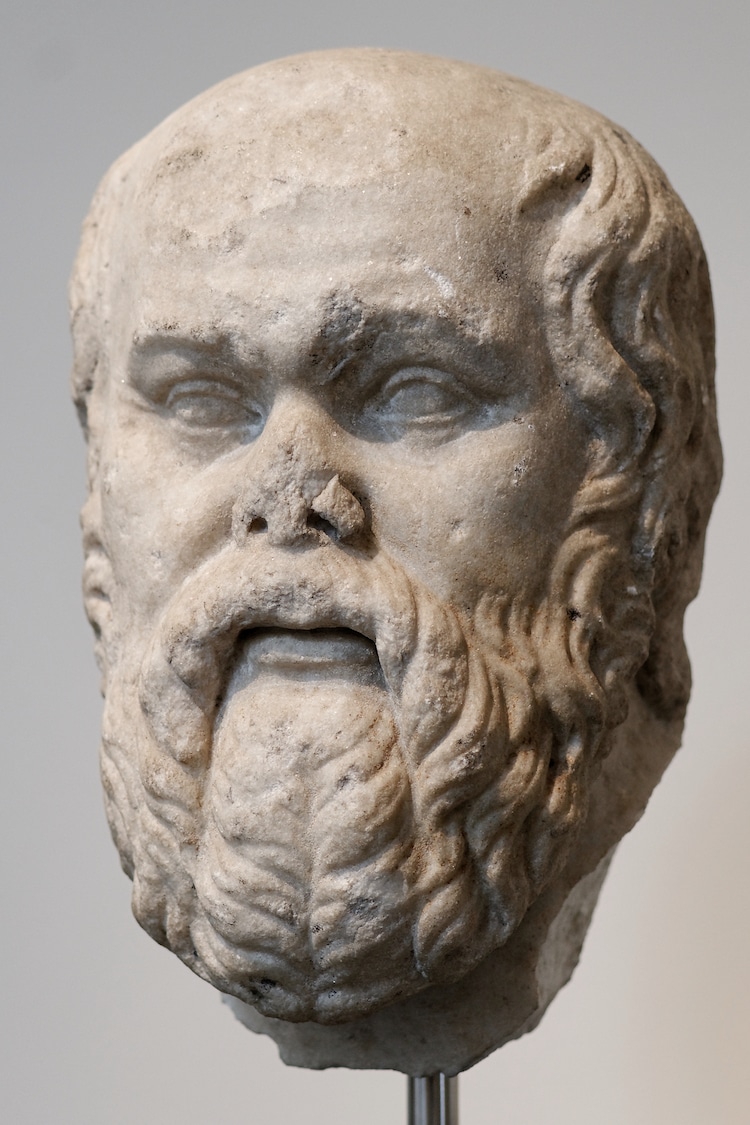

Bust of Socrates, ca. 1st-2nd century (Photo: Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.5)

The Death of Socrates portrays the real-life execution of Socrates, a Greek philosopher who helped pioneer Western philosophy, in 399 BCE. Using Plato's Phaedo as a reference, David captures the moment that Socrates—who had been sentenced to death by the Athenian courts for “impiety” and “corrupting the young”—is given poison hemlock to drink.

As he willingly reaches for the cup, he continues to preach to his young followers, illustrating both his respect for the democratically reached decision and his dedication to philosophy. According to Plato, after humbly thanking the Greek god of health for a peaceful death, Socrates “raised the cup to his lips and very cheerfully and quietly drained it.”

Though this event actually happened, David took some artistic license when documenting it. This is especially true of the figures he opted to include in the painting. While Socrates (1), his followers Simmias and Cebes (2 and 3), Crito (4), Apollodorus (6), and his family members (7), were beloved to be present, Plato (5) and the remaining figures were not.

Harmonious Composition

Jacques Louis David, “The Oath of the Horatii,” 1784 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Neoclassical artists approached composition with just as much intention as content. Specifically, they strived to achieve balance in their works, culminating in scenes that almost appear to be set on a stage.

This is particularly apparent in the paintings of David, including The Death of Socrates and his equally famous Oath of the Horatii. In both cases, he opted to arrange the figures in a staged fashion. Though they are shown interacting with one another, their movements are posed and their expressions are stoic. This distinctive approach to placement is due to David's disregard for emotion and preference for balance and detail—a quality that is also present in his draughtsmanship.

Precise Draughtsmanship

Jacques Louis David, “The Death of Socrates, 1782 (detail of sketch) (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Public Domain)

A third major characteristic of Neoclassical painting is precise draughtsmanship. David is renowned for his use of bold, strong lines and minimal ornamentation. Though this aspect is illustrated in the completed Death of Socrates painting, it is even more evident in the preliminary sketches that he produced for the piece. Stripped of all color, tonality, and treatment of light, these drawings accentuate his simplistic approach to his craft—and, ultimately, his general ideas on art.

“In the arts,” he said, “the way in which an idea is rendered, and the manner in which it is expressed, is much more important than the idea itself.”

The Death of Socrates Today

The Death of Socrates is housed by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Since joining the museum's permanent collection in the early 20th century, it has been featured in several exhibitions, both in the United States and abroad. As a staple of the museum's collection, the Met no longer lends it to other institutions. So, if you want to gaze upon David's “most perfect statement of the Neoclassical style” for yourself, you must make your way to New York City!

DON’T FORGET YOUR CITYPASS!

My Modern Met Tip: CityPASS is the best way to see New York City’s top attractions—they’re bundled to save you 42% on admission. Included are The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Guggenheim Museum, Ferry Access to Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, 9/11 Memorial & Museum, and Empire State Building. And better yet, when you have the pass, you’ll get priority entry into some of them. It’s a win-win!

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON NEW YORK CITY:

Check out NYCgo: the Official Guide to New York City.

Related Articles:

Exploring the Heavenly History of Angels in Art

The History of Cupid in Art: How the God of Love Has Inspired Artists for Centuries

Architecture 101: 10 Architectural Styles That Define Western Society