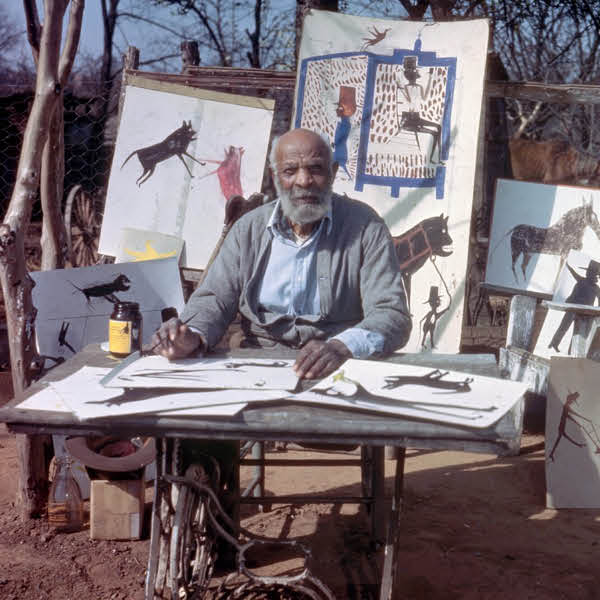

James McNeill Whistler, “Arrangement in gray: portrait of the painter,” ca. 1872 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In 1871, American artist James McNeill Whistler completed one of today's most famous paintings. Known colloquially as Whistler's Mother, Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1 has captivated viewers with its understated simplicity and straightforward composition for nearly 150 years. While this piece is arguably Whistler's most famous creation, it is not the only thing worth knowing about the artist, whose life story includes foreign homes, feuds with friends, and even fighting peacocks.

Want to learn more about this iconic artist? Here are five facts about James McNeill Whistler.

He developed an interest in art as a child living in Russia.

William Edward Kilburn, Daguerreotype of James McNeil Whistler, ca. 1847-1849(Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

In 1834, James Abbott McNeill Whistler was born in Lowell, Massachusetts—a hometown he would later renounce. “I shall be born when and where I want,” he declared in 1877, “and I do not choose to be born in Lowell.” Though a rejection of one's birthplace may sound strange, Whistler led an international lifestyle from a young age. Following a move to Connecticut in 1837, his family relocated to St. Petersburg, Russia when Whistler was just 8 years old.

It is during his time in St. Petersburg that Whistler discovered and developed his artistic talents. Following two years at the Imperial Academy of Arts, he and his mother moved to London, where he informally studied photography and art under the direction of his brother-in-law. Seemingly on a straight path toward a successful art career, Whistler's plans changed in 1849, when his father—a prominent engineer—died of cholera and his family returned to Connecticut.

He considered serving in the ministry, joining the military, and working as a mapmaker before studying art in Paris.

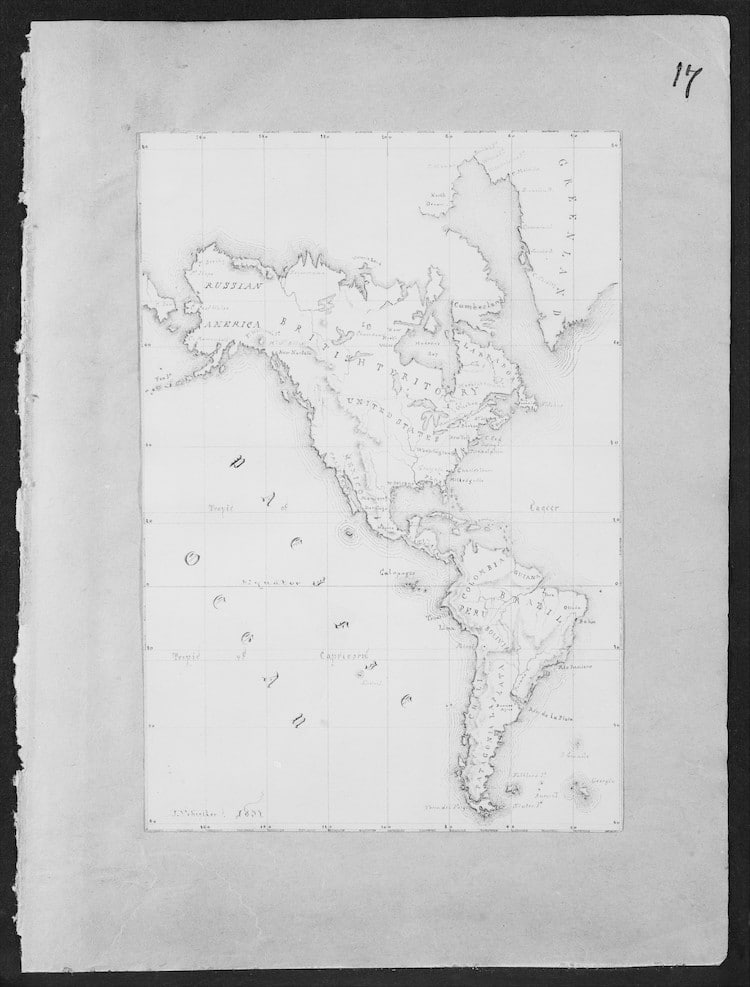

James McNeill Whistler , Map of the Western Hemisphere (from Sketchbook), 1851(Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Public Domain)

Following the death of her husband, Whistler's mother enrolled her son in a preparatory school run by a reverend. While she had hoped such schooling would lead him on a path toward a career in the ministry, he instead spent his time sketching caricatures and eventually entered—and flunked out of—military school.

Whistler then worked as a military and maritime cartographer. While his skillfully drawn work showed promise, he was repeatedly late and notoriously lazy. It was his habit of filling his maps with mermaids, sea monsters, and other mythical creatures, however, that finally cost him his job.

After these unsuccessful stints, he decided to pursue art as a profession. In 1855, he moved to Paris, where he studied art (both in academic settings and on his own merit). Though he spent his first three years in the French capital overindulging and underperforming, he started taking his practice seriously in 1858, when he entered the social circle of Realist master Gustave Courbet.

He gave his paintings titles inspired by music terminology.

James McNeill Whistler, “Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket,” 1875 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Over the next ten years, Whistler made a name for himself in both Paris and London (where he moved in 1859) with his tonal paintings. Serving simply as studies of color and lacking underlying meanings, these works illustrate Whistler's interest in creating “art for art's sake.” This detached approach to art is among the artist's most prominent legacies, on par with his tendency to give paintings musical names.

“Nocturne,” “harmony,” and “symphony” are just some of the terms Whistler opted to feature in his titles. Inspired by the belief that “music is the poetry of sound, so is painting the poetry of sight, and the subject-matter has nothing to do with harmony of sound or of color,” the artist started giving his paintings lyrical titles in the early 1870s, with Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1 as an early—and particularly well-known— example.

There's an Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 2.

James McNeill Whistler, “Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1,” 1871 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1 is a portrait of the artist's mother, 67-year-old Anna McNeill Whistler. It was completed in 1871, five years after Whistler's mother decided to join him in London.

In addition to showcasing Whistler's focus on color, which he explored through shape, form, and composition, the austere painting also illustrates the artist's perception of his pious mother, whose presence in London—previously the setting of his Bohemian lifestyle—he described as a “general upheaval” in a letter to fellow artist and friend Henri Fantin-Latour.

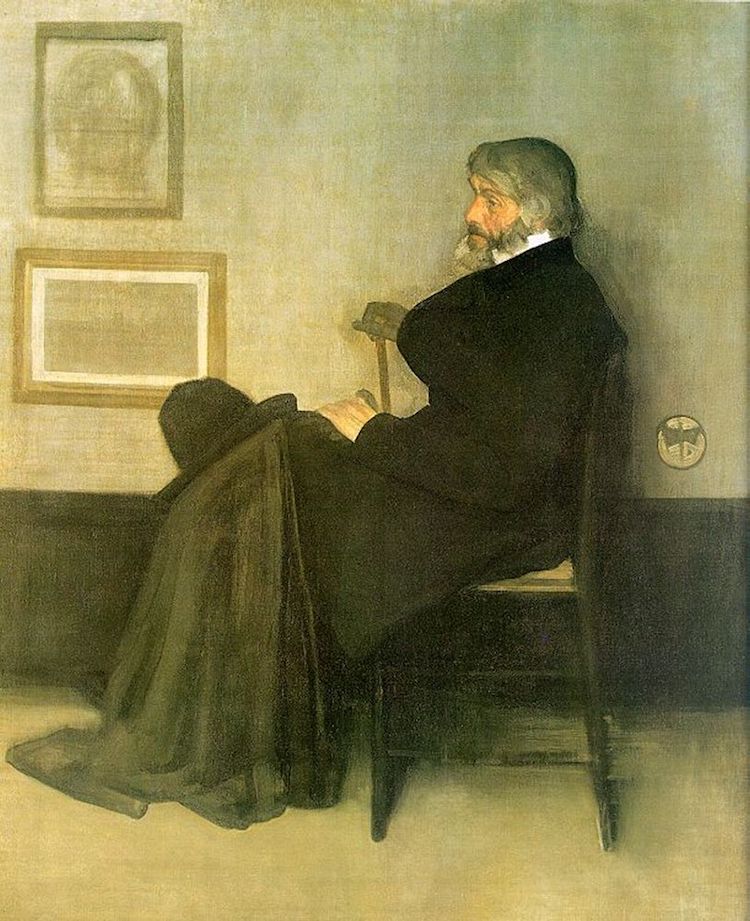

With its basic composition, mundane subject matter, and somber color palette, many of Whistler's contemporaries criticized the work. To Thomas Carlyle, a Scottish historian, satirist, philosopher, and mathematician, however, it was those very qualities that made it memorable. This prompted him to commission Whistler to produce Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 2, a copycat portrait starring Carlyle.

James McNeill Whistler, “Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 2,” 1873 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

“He liked the simplicity of it, the old lady sitting with her hands in her lap, and said he would be painted,” Whistler explained. “And he came one morning soon, and he sat down, and I had the canvas ready, and my brushes and palette, and Carlyle said, ‘And now, mon, fire away!'”

His life was filled with feuds.

The Peacock Room (Photo: Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

While Whistler's collaboration with Carlyle proved fruitful (Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 2 remains one of his most important portraits), not all of his relationships went well. In fact, he frequently fought—and even fell out with—friends and fellow artists alike. Famous examples include Courbet (who caused a stir when he painted Whistler's girlfriend in the nude in 1864); William Merritt Chase (who called Whistler a “veritable tyrant”); and art critic John Ruskin (who Whistler sued for libel after he likened his art to “flinging a pot of paint in the public's face”).

The most infamous of Whistler's many feuds, however, was with Frederick Richards Leyland. Leyland, an English shipping magnate, possessed a prolific collection of Chinese porcelain. In the 1870s, he commissioned architect Thomas Jeckyll to design and craft a room in his London home to display these wares. When Jeckyll began having health problems while Reyland was out of town, however, Whistler was brought on-board—and immediately all previous plans were abandoned.

“Well, you know, I just painted on,” he recalled. “I went on—without design or sketch—putting in every touch with such freedom … And the harmony in blue and gold developing, you know, I forgot everything in my joy of it.” When Leyland learned about the liberties Whistler had taken, however, he did not share this joy. In fact, he refused to pay Whistler in full. Whistler, in turn, responded by adorning the room with Art and Money; or, the Story of the Room, a symbolic mural featuring two fighting peacocks.

Housed by the Smithsonian since 1906, the Peacock Room now sits in the Freer Sackler Gallery in Washington, DC, where it remains a highlight of the collection—and, in more ways than one, a symbol of Whistler's life and career.

Related Articles:

8 Real-Life People Who Became the Stars of Art History’s Most Famous Paintings

The Life and Work of J.M.W. Turner: One of the Most Influential Figures of Modern Art

How the Groundbreaking Realism Movement Revolutionized Art History