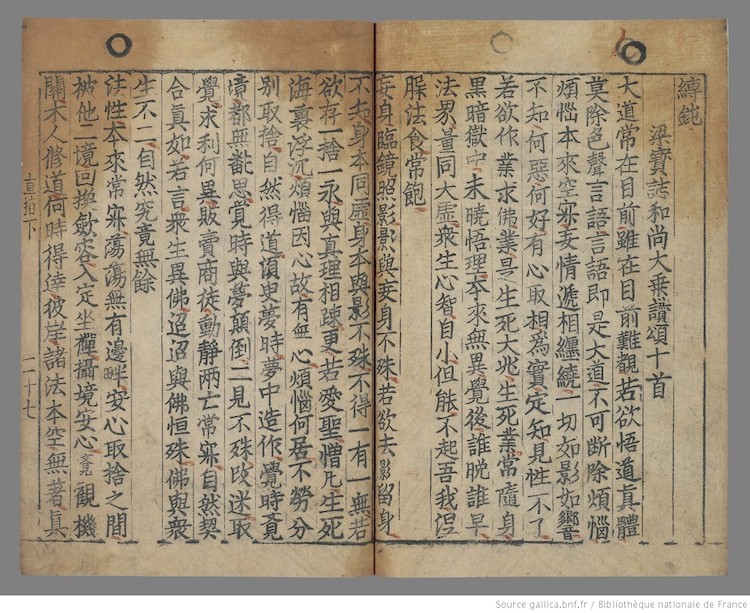

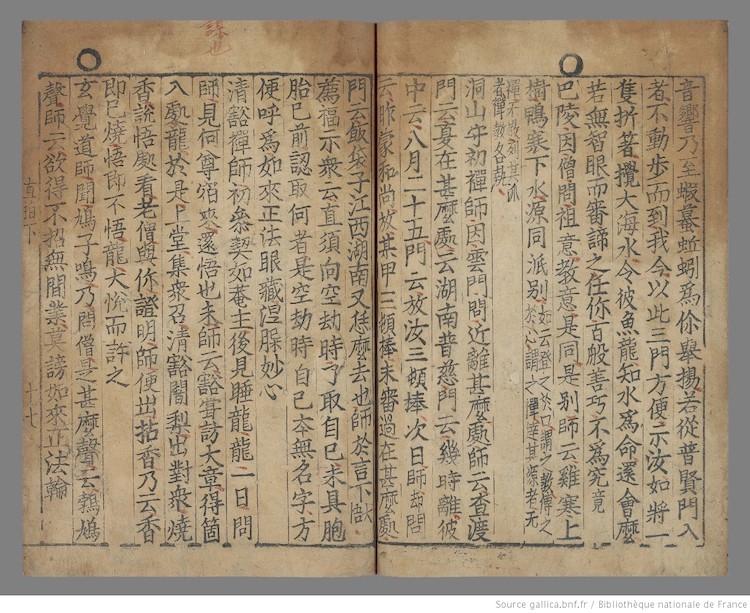

Jikji, 1377. (Photo: BnF)

Today, the printed word is taken for granted. Newspapers, books, brochures, and business cards are filled with printed words essential for spreading information around the globe. The revolution of the printed word came about with the advent of moveable type—technology that allowed quick, quality reproductions of text. While many associate the world-famous Gutenberg Bible with this technology, it's actually not the first book ever printed. In fact, work coming out of Asia beats it by a long shot.

The arrival of metallic moveable type in Europe is indebted to Johannes Gutenberg; however, far earlier, the printing technique was used in China and Korea. The use of metal was fundamental, as it was far more durable than earlier wood or ceramic type—though this was also pioneered by the Chinese. Experts believe that bronze moveable type was already in China no later than the 12th century. This places the Chinese well ahead of Gutenberg, whose revolutionary Gutenberg Bible wasn't printed until the mid-15th century.

However, while the Chinese were using moveable type at an early date, they weren't necessarily printing books. Government documents and currency were the first materials created using the technique. One has to look to Korea for the earliest printed books, as they began printing texts using metallic type in the early 13th century. While the oldest books haven't survived, one religious text takes home the title as the world's oldest book printed with metallic moveable type—the Jikji.

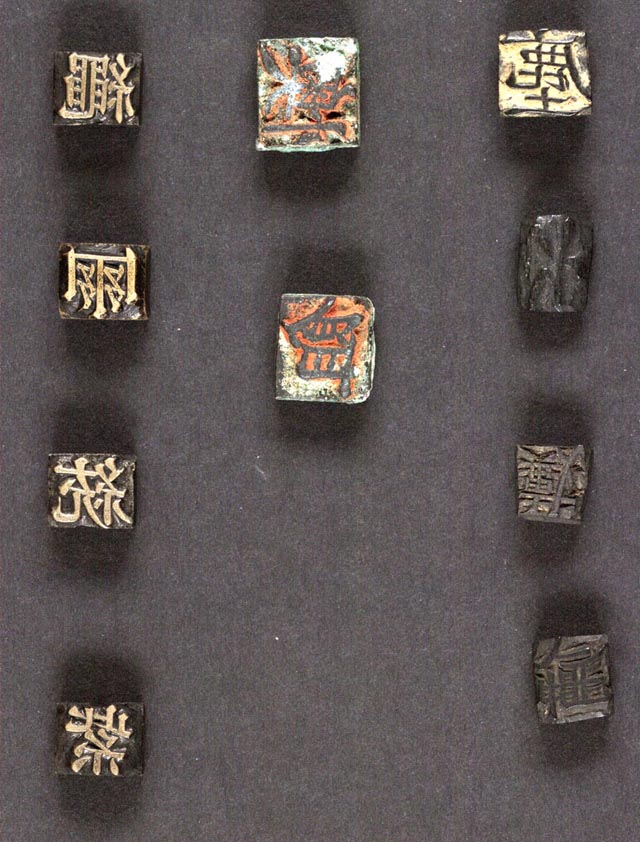

13th-century Korean type specimens. (Photo: Library of Congress)

This anthology of Buddhist priests' Zen teachings was printed in 1377, predating the Gutenberg Bible by 78 years. Though only one copy of the second volume survives, it has been digitized and placed online by the National Library of France. Scholars have called the printing technique used in the Jikji very similar to the one that Gutenberg later developed, with bronze casting techniques used for coins adapted to create metal type. With this in mind, the commonly held belief that Gutenberg is solely responsible for the printing revolution becomes a Euro-centric vision of how printing developed, discounting the earlier advances of the Chinese and Koreans.

What is true is that Gutenberg benefited greatly from how widely the texts using his technique were disseminated. Writer M. Sophia Newman points out that printed books from Korea didn't enjoy the same distribution. She attributes this partially to the fact that Korea was under invasion at the time, as well as the complexities of the Korean language, which made assembling pages notably slower.

Luckily, more light is being shed on the wider collective that helped push forward printing technology. This, of course, includes Gutenberg, but also the Chinese and Korean printmakers responsible for moveable type. To emphasize that importance, the Jikji was placed on UNESCO's register in 2001 as part of the Memory of the World Programme, which aims to safeguard the heritage of humanity.

Jikji, 1377. (Photo: BnF)

h/t: [Lithub]

Related Articles:

This Jewel Box at Yale Is America’s Largest Building Dedicated to Rare Books

Europe’s Oldest Intact Book Is Discovered Inside the Coffin of a Saint

World’s Oldest Multicolor Book, a Chinese Calligraphy & Painting Manual, Now Available Online

This 4,000-Year-Old Tablet Could Be the World’s Oldest Customer Service Complaint