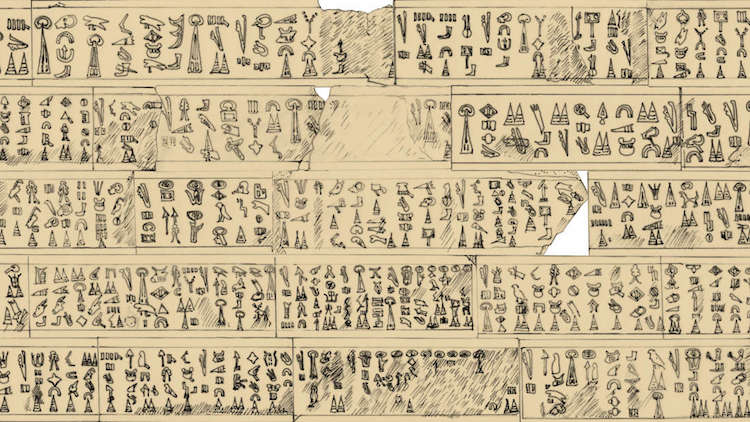

Luwian hieroglyphics.

In 1878, villagers in the small Turkish village of Beyköy discovered a 14-inch (35-cm) tall and 95-foot-long limestone frieze filled with hieroglyphic inscriptions of an unknown language. It would take 70 years before scholars could even read the language, which is now known as Luwian. And now, 3,200 years after its creation, scholars have deciphered the meaning of the frieze.

This ancient language of what is modern-day northern Syria and western Turkey went extinct around 600 BC, but not before the creation of the frieze, which is the longest Bronze Age hieroglyphic inscription. At the time of its discovery, French archaeologist Georges Perrot carefully copied the inscription before the piece of limestone was hauled away to be used in the construction of a mosque.

These inscriptions, and subsequent copies, were lost until the 2012 discovery of Perrot's copy in the estate of famous archeologist James Mellaart. Now, a team of Swiss and German archaeologists says they have unlocked the key to the inscription and its marvelous story. According to Eberhard Zangger, president of Luwian Studies, the frieze recounts the wars, battles, and invasions of prince Muksus. This Bronze Age prince was from the kingdom of Mira, which controlled Troy.

Some people believe that the Luwians are the “Sea People” that were said to have driven the end of Egypt's New Kingdom. Zangger—taking things a step further—feels that they may have fueled the collapse of Bronze Age superpowers by starting a series of conflicts called World War Zero.

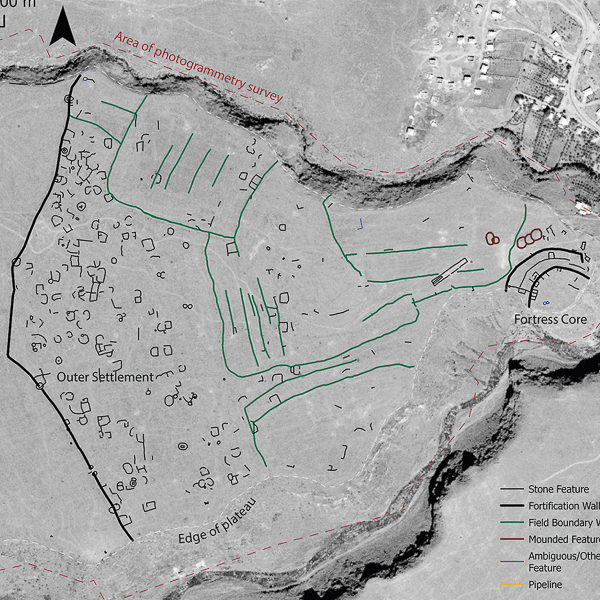

Map of where Luwian was spoken at the end of the Bronze Age.

With only two dozen people in the world who can read Luwian and a 95-foot-long frieze to decipher, it's an incredible accomplishment to have translated these stories. “According to the inscription, the Luwians from western Asia Minor contributed decisively to the so-called Sea Peoples' invasions—and thus to the end of the Bronze Age in the eastern Mediterranean,” states Zangger in the Luwian Studies press release.

Some scholars remain skeptical of the findings, pointing to the fact that the team is working with a copy of unknown accuracy which could be a forgery. Others point out that it would be difficult for anyone to forge such a long inscription, especially as Mellaart himself did not understand Luwian. The team's full findings will be published in the journal Proceedings of the Dutch Archeological and Historical Society's December issue, allowing us to discover more about this mysterious Bronze Age tale.

h/t: [Atlas Obscura, IFL Science!]

All images via Luwian Studies.

Related Articles:

New Study Suggests That Man May Not Originate From Africa After All

World’s Oldest Written Language Has Its Own Dictionary Available Online for Free

Primitive Drawings Discovered on “Newspaper Rock” Reveal Daily Life From 2,000 Years Ago

3,500-Year-Old Unfinished Obelisk Reveals Incredible Engineering of Ancient Egypt