Margaret Wise Brown by Consuelo Kanaga (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

Brown took this dreamy yet down-to-earth approach to new heights with Goodnight Moon, a sentimental story about a tiny rabbit's nightly routine. When this little book was published over 70 years ago, it put Brown's name on the map—and landed her a spot as one of children's literature's most influential figures.

Learn all about beloved children's book author, Margaret Wise Brown, with these five fascinating facts.

She helped pioneer and popularized the “here and now” style of children's books.

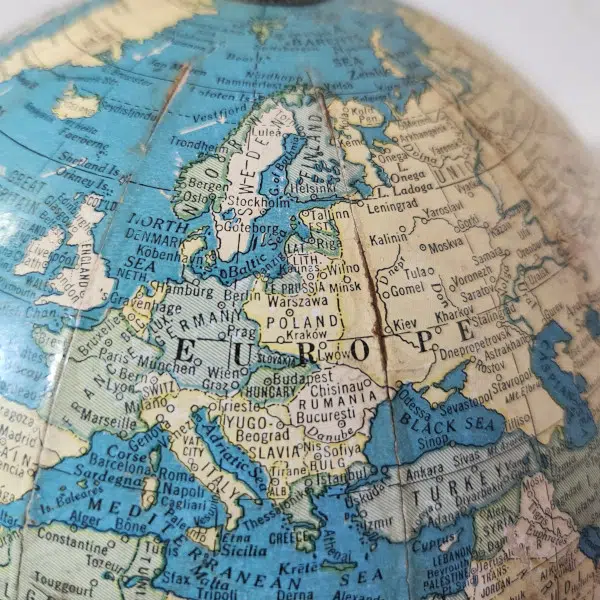

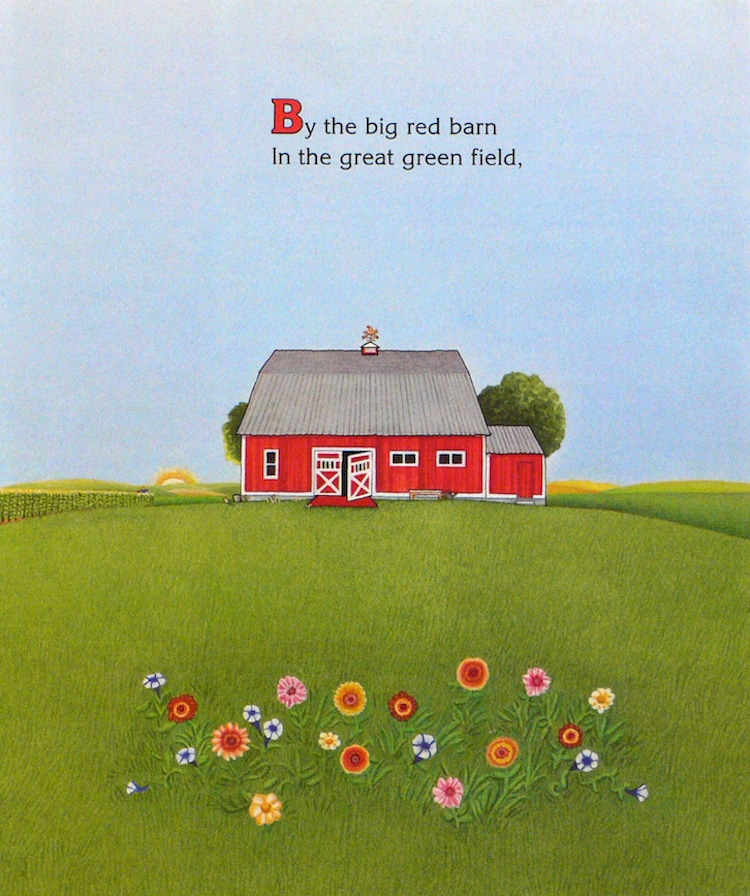

Excerpt from “Big Red Barn,” 1954 (Illustrated by Felicia Bond) (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

It is at Bank Street Experimental School where Brown was introduced to a new style of writing: “here and now.” Pioneered by the school's founder, Lucy Sprague Mitchell, this avant-garde genre was based on Mitchell's research-backed belief that young children did not desire over-the-top fairytales or silly nursery rhymes; instead, they simply wanted to explore the wonderful world of the “here and now.” Brown had such faith in this approach that, in 1938, she joined Mitchell at William R. Scott, a publishing house, where she worked as an editor.

While working at William R. Scott, Brown—who had published her first children's book, When the Wind Blew, in 1937—harnessed the “here and now” approach and began writing in earnest. Though she saw success with works like The Noisy Book and The Golden Egg Book, it was Goodnight Moon that made her a household name.

Goodnight Moon was banned by the New York Public Library.

The lion statues at the New York Public Library,1954 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

In 1947, the book was banned by the New York Public Library at the request of Anne Carroll Moore, the former head of the institution's children's services. While Moore had left the library six years prior, staff still filled their shelves with books graced with Moore's stamp of approval—literally. If Moore did not believe a certain title had a place at the library, she would emblazon it with an inked message: “Not recommended for purchase by expert.” Goodnight Moon met Moore's criteria for a no-go; she viewed it as “overly sentimental,” and persuaded the library to reject it.

While Moore's harsh review initially impacted the book's sales, it eventually found its footing a decade later, and, in 1972, it finally made its way to the New York Public Library.

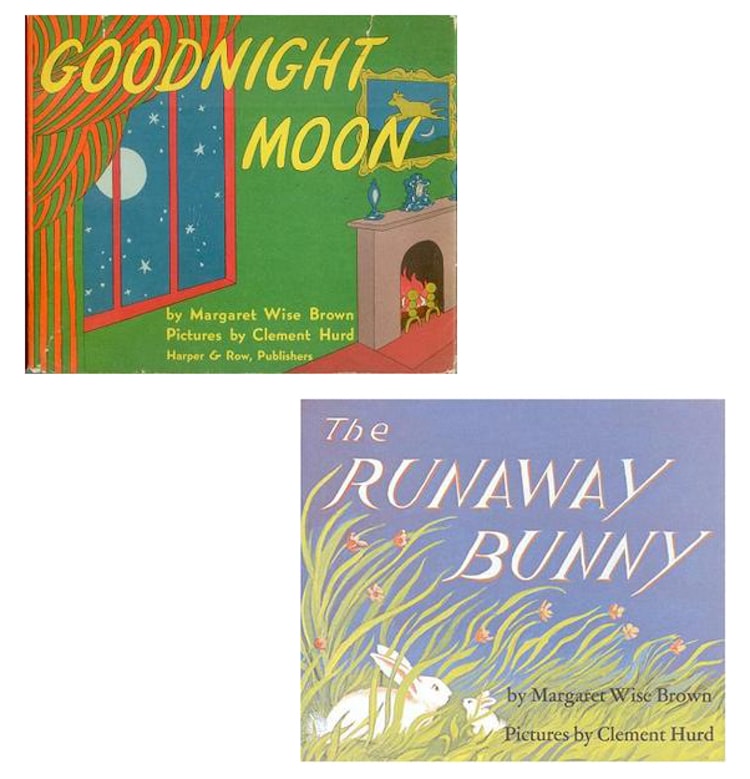

Her collaboration with Clement Hurd is one of her many important relationships.

(Photo: [left] Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain]; [right] Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

Brown's collaboration with Hurd is not her only noteworthy relationship. She also had a professional partnership with renowned collector Gertrude Stein, and was romantically involved with Blanche Oelrichs, a woman, and James Stillman Rockefeller Jr., the great-nephew of J.D. Rockefeller

She wrote using several noms de plume.

Margaret Wise Brown by Consuelo Kanaga (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

This would have been neither the first nor the last time that Brown would opt to use a nom de plume. Over the years, she adopted various alter egos, including Juniper Sage, Timothy Hay, and, most frequently, Golden McDonald.

Over 70 unpublished manuscripts were found hidden in a hayloft decades after her death.

Margaret Wise Brown by Consuelo Kanaga (Photo: Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

In 1990, researcher Amy Gary found a trunk filled with over 70 unpublished manuscripts in a barn belonging to Brown's sister, Roberta. Comprising 500 pages, this treasure trove has since been catalogued and edited by Gary, who helped publish the stories and even wrote a biography about Brown. Together, these efforts shine a light on an already luminous legacy and, ultimately, illustrate one of Brown's most famous assertions: “Everything that anyone would ever look for is usually where they find it.”

Related Articles:

The Art of Beatrix Potter: From Scientific Studies to Beloved Children’s Books

New York Public Library Reveals 10 Most Borrowed Books of All Time

These Rare Classic Children’s Books Can Now Be Read Online for Free