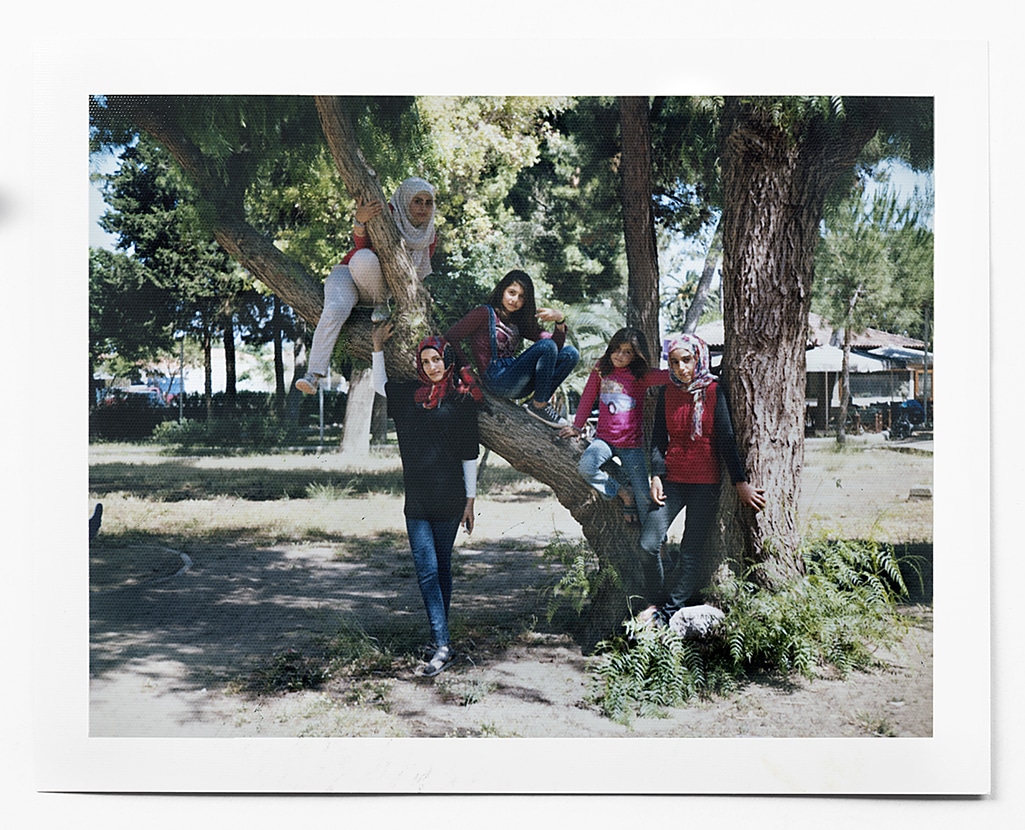

Mirian, second from left, and her Sisters, from Afganistan, posing in front of National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

Athens, Greece, April 2016.

The four sisters and their brother are now in Austria.

Since 2015, photographer Giovanna Del Sarto has been documenting Europe's refugee crisis through her unique project, A Polaroid for a Refugee. Asking her subjects to pose, but not giving them any direction on how to do so, she snaps Polaroid photographs that not only document the current situation of these refugees, but gives them a gift—as each is also given a photograph in exchange.

For almost two years, Del Sarto has moved through locations in Serbia and Greece to get firsthand experience with the crisis. Whether working at the information tent at the Presevo transit camp in Serbia or joining a Norwegian NGO in night patrolling Lesvos, a Greek island close to the Turkish Coast, her work has brought her into close contact with men, women, and children who have been forced to flee their homes.

And while the refugee crisis has been well covered by photojournalists, A Polaroid for a Refugee has seen great success for the emotional core it touches. The glimpses of pride in their poses and tired traces in their eyes gives a profoundly human glimpse into what is often reduced to a news headline. We had the opportunity to speak with the Italian-born, London-based photographer about her work, how she started using the Polaroid, and her next steps in our exclusive interview, below.

A little boy in the field by Vial Camp.

Vial Camp, Chios, Greece, May 2016.

Chios Island is one of the closest Greek islands to the Turkish coast and as such, a prime point of entry to Europe.

Last year, the entrance to the Vial camp was granted only to the NGO and Charities who were directly involved with the well-being of the refugees.

Due to the deal with EU and Turkey, most of the reception refugee camps became detention camps in which refugees were kept under police supervision as Amnesty International reported after being granted access to Vial Camp in April 2016. “Security concerns linger following fierce clashes that broke out between different nationalities inside the camp overnight on 1 April, prompting more than 400 refugees and migrants to escape” according to Amnesty International.

Can you share a bit about your background in photography and what drew you toward photojournalism?

Photography came late into my life. When I was a teenager I did not like photography for its limitation in depicting reality. I do not know when this attitude changed. By the time I was twenty, I started using photography to document my life, as all of us do.

I became interested in photojournalism after a trip in the Balkans in 2003. Experiencing the aftermath of a war made me feel the urge to document aspects of reality which are left undocumented due to their lack of headline sensationalism.

In 2008, I attended a Master in Documentary Photography and Photojournalism at LCC (London College of Communication) in London. Since then, I have been following my own heart and interest in what I would like to photograph.

A kid laying on the top of yellow concreate barrier by the manshift camp at Piraeus Port

Piraeus Port, Greece, April 2016.

The night before, the overcrowded refugee settlement at Piraeus Port was the scene of clashes between Syrian and Afghan refugees, as reported by the national and international press. Consequently, the police dismantled a particular area and took people to different camps around Athens, according to eyewitnesses.

Who are your inspirations in terms of other documentary photographers?

My very first love was, and still is, Sebastiao Salgado. He is such an amazing photographer and human being.

Soon after, I started following Ron Haviv, Ida Kar, Susan Meiselas, Lynsey D’Addario, Monika Bulaj, Fausto Podavini, to mention a few.

You mention feeling drawn into action in 2015 after reading so much about the current refugee crisis in Europe. Can you talk a bit about your feelings and what in particular made you feel like you needed to witness it?

I wanted to be able to draw my own opinion about the crisis. It's very easy to get “refugee fatigue” after so many months of reading articles, watching TV, and talking to people who might share your view—or not. At the end, you get confused. So, considering that I could go, I did. I took some days off from work and I went to the south of Serbia without exactly knowing what to expect.

What I saw in Presevo was a sea of people trying to go towards the unknown. Europe is the unknown for them, as much as the Middle East would be for us despite the fact that we might be familiar with their culture, customs, and so on.

That thought made me understand that no matter what you read in newspapers, watch on TV or talk about with people, the reality is always far more complicated than what we think. It's super convenient to house everything under an umbrella called REFUGEE CRISIS, but it is far more complicated to envision the single, ordinary needs people have.

That's why I decided to go, volunteer and take pictures. I needed to touch that ordinary life which has been displaced.

Presevo, Serbia, 2015.

Have you always used a Polaroid in your work?

No. Never before. I have always liked Polaroid. I always choose very well known high-resolution cameras for all my work, from Hasselblad to Mamiya to Nikon. Using Polaroid was a new adventure for me too.

I knew that Polaroid would make everything easier on both sides. It’s so playful and so forgiving. You are not tempted to take 10 portraits of the same person—it would bankrupt you. Under these circumstances, you also do not want to impose yourself upon people.

Two young refugee women posing for a portrait soon after their arrival on Lesvos Island.

Skala, Lesvos, Greece, January 2016.

The girl on the right is still wearing the emergency blanket given to her after reaching the shore to keep her body temperature stable.

How did using the Polaroid as a tool come about? I’m curious to know if you had other equipment with you and switched to using it or if it was always your intention to use the Polaroid as an instrument for documentation.

I usually have two cameras with me, my Polaroid 103 and my Nikon D3S with a 35mm lens. I use the Nikon only to record my whereabouts, the surroundings where the Polaroids are taken. In doing that, I can fully document the project. Obviously, Polaroid pictures are also used for specific landscapes or pictures of details.

There are a few main reasons why I use the Polaroid.

First, the project is based on the concept of giving back, giving something back to people who are in transit, who might make it to their destination or might not. Either way, they might look back to that small picture in the future or they might simply pass it on to family members. This is my romantic idea at the heart of my project.

Second, we all love a nice family portrait. We love to pose and show the best of us, even in difficult situations. We are resilient human beings, that is what we are. I wanted to show this. Most of the images we get are images of despair and difficulties, but, in harsh situations, people still have a laugh. I was aware that there were a lot of good photographers out there doing a great job. What could I have added to it? As I said at the beginning, I started this project more as a personal discovery rather than a photographic project.

And lastly, how many times have I promised to send pictures to my subjects? The list is so long and gets longer. Polaroid is my redemption.

Jude, traveling with her family, just arrived at the Presevo Info tent.

Presevo, Serbia, October 2015

I asked the subjects to pose, but I did not direct the scene. The subjects decided where and how to pose.

The original picture is a Polaroid Fujifilm FP-100C, which I re-photographed with Nikon 800 in my studio.

Can you share the story of the first person you approached with the Polaroid and their reaction?

To be honest, I do not remember the first person I approached, but rather the first trip. I was in Presevo working at the info point tent. I was shocked about how many people were coming by bus and on foot. I started photographing little by little. Observing a lot first. I remember that I was volunteering at the info tent when I saw this young girl approaching us with her family. I loved the way she was wearing the blanket as if it was a fashion icon. I asked her family permission to photograph her. Her name is Jude and she is from Syria.

Later in the day, I posted the picture on Facebook.

A few days later, a photographer wrote to me and told me that he met the same girl on her arrival on Lesvos island and she was giving birth on the shore. I saw his picture and the resemblance is there. I might never know if it's the same person but this will be the anecdote which will be always mentioned about Jude from Syria.

Mohammed Jarusha and his wife posing for a Polaroid in their family tent.

Idomeni Camp, Idomeni, Greece, April 2016.

How do you think using the Polaroid helps in creating a connection with your subjects?

It helps a lot. It's something different in people's lives and their routine within the refugee camps.

The connection is created during the time you want them to take part in the photographic procedure of developing the image. I usually ask the subject to lift their arm and slide the photo under their armpit and ask them to keep it warm for two minutes. Here we are laughing, and sometimes talking about the situation, while waiting for the picture to develop.

Before my departure, I usually write my email address on the back of their Polaroid asking them to write to me once they reach their destinations.

Presevo, Serbia, 2015.

How do you feel your work is unique from other photojournalists covering the refugee crisis?

Good question. Apart from the usage of Polaroid film, A Polaroid for a Refugee is a slow project. I am not there to record the latest evolution of the crisis as a photojournalist does. I am there at my own pace, and to try to reason with it while embedding myself; to understand them as people and not treat them in the landscape of the crisis.

Idomeni, Greece.

Since 2015, you mention having continued your travels. What is the last trip you made and do you intend on continuing the project?

My last trip was at the beginning of June 2017. I went back to Presevo. I was part of Border Free Association from Switzerland. I gained access to the camp where I taught a bit of English during English classes.

To be honest, nowadays, I do less volunteering and more photography. This is due to a different situation. People are stuck in camps and having somebody with the camera and giving pictures away is a rather entertaining event. So, my Polaroid became my volunteer job.

My next trip is to Austria, Switzerland, and Germany. I am in contact with some of the people who made it to their destination and now, I want to follow up their stories. After that, I am going back to properly volunteer with Border Free and get to know people a bit more. I am curious about their current lives and their journeys towards their destinations. This time I might not take any Polaroids. I would like to get to know people a bit more.

Idomeni, Greece.

What do you hope that people take away from the work?

My intention is to simply show who are the people behind this current crisis. Sometimes, it is easy to forget that we live in the same unstable world….it could have been us receiving a Polaroid.

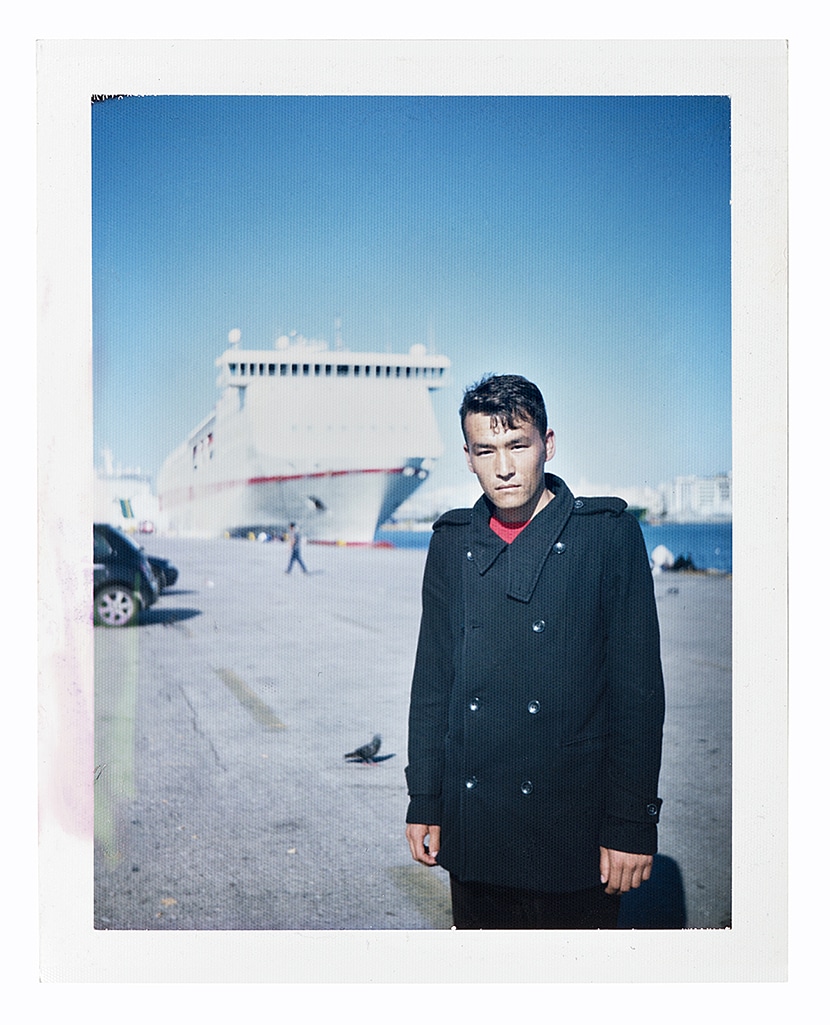

Mahbub from Afghanistan poses for his portrait at Piraeus Port.

Piraeus Port, Greece, April 2016.

After several months, Mahbub managed to reach Switzerland and now lives in Lucerne. He is attending German classes. After the borders started closing across Europe, more and more people began contacting smugglers in their attempt to continue their journeys, according to Aljazeera.

Are there any photographs that stand out to you as especially meaningful?

Of course, despite the fact I love all of them.

Mahbub Pardis is 25 years old and from Afganistan. I briefly met Mahbub in Piraeus port in April 2016. I gave him my Facebook details with the wish to be contacted once he reached his destination. A few months later Mahbub wrote to me from Switzerland. In September 2016, A Polaroid for a Refugee was one of the winners of Lugano Photo Day in Lugano, Switzerland. Mahbub came to the opening and he saw his portrait being chosen for the back cover of the official catalog. In a few weeks, I am going to Lucerne to visit him and see how life is for him.

Somaya (13) and Snaz (17) from Afganistan.

Presevo Camp, Presevo, Serbia, 2017

Somaya, 13 years old, and Snaz, 17 years old, are two sisters who are in Presevo camp. Their story started about 2 years ago when they left their country with all their family. They traveled through Iran, Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, and Serbia. Unfortunately, their parents were deported back to Afghanistan once they arrived in Iran. They were traveling in two different cars. Their parents' car was stopped by the police, while their car was not. They are in the camp with their younger brothers (12 and 2) and Snaz’s husband.

Miral, 7 years old, from Afganistan.

Presevo Camp, Presevo, Serbia, 2017

Miral, 7 years old, from Afganistan, had been in the Presevo camp for several months when I met her. She is with her parents and brother and sister. Her perfect English surprised me. I asked her if she could speak English before leaving Afghanistan. She said no. She learned it as a consequence of her displacement.

Idomeni, Greece.

What would you like people at home to know about the refugee crisis in Europe after seeing it up close and personal?

Personally, I think that we need to understand that refugees, who put their lives in peril to come to Europe or to any other country, do not have their mindset on taking over people's jobs, houses or economy. They are escaping a situation that is unbearable to stand anymore.

I know it is difficult to imagine people moving into your country, but it is more difficult to imagine yourself not being accepted in somebody else's country.

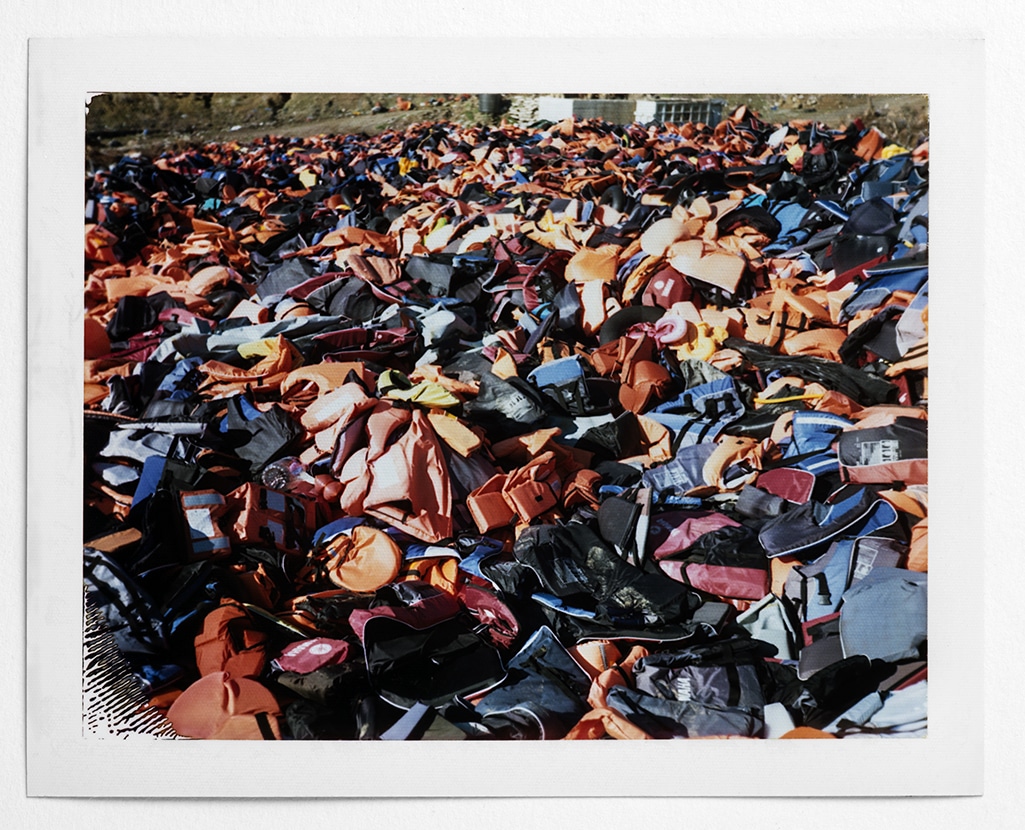

Detail of a life jacket graveyard on Lesvos.

Molovos, Lesvos, Greece, January 2016.

According to the BBC, last year the Turkish police announced they had confiscated many fake life jackets produced in Turkey and intended for sale to refugees.

Presevo, Serbia, 2015.

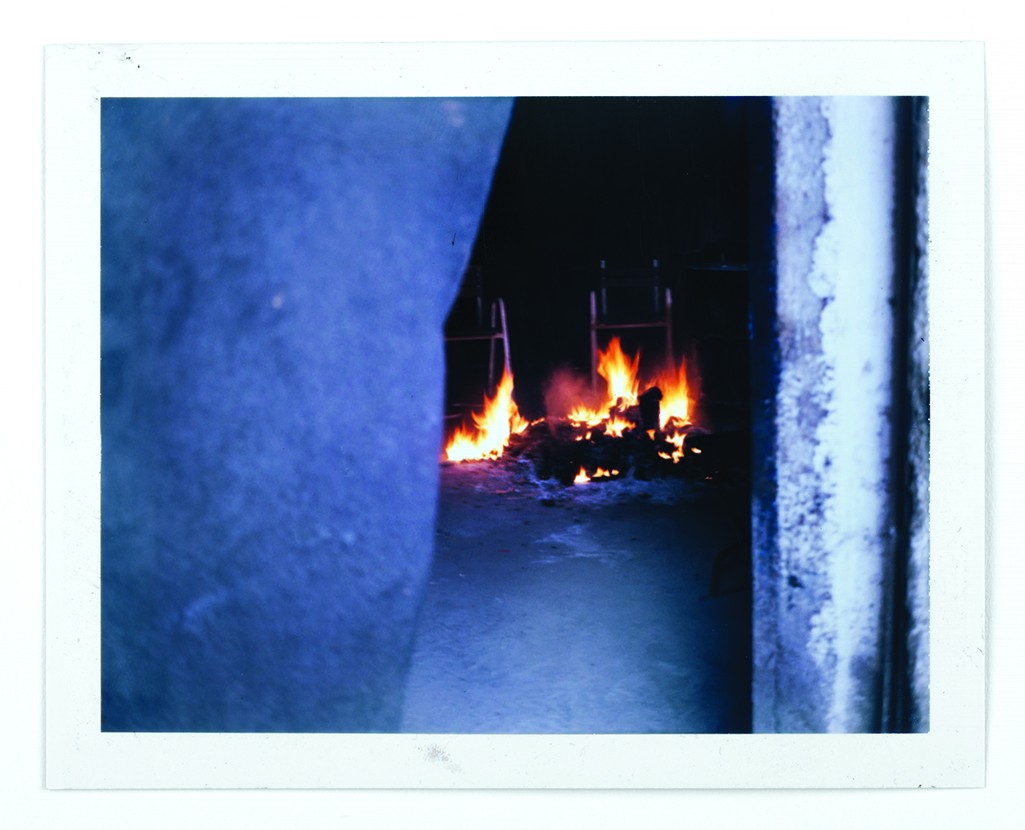

Barracks behind Central Train Station, Belgrade, Serbia, 2017

Detail of the barracks behind Belgrade Station where over 1000 young men lived in a squalid situation for months.

Now, the barracks have been evacuated and most of their guests have been sent to different camps in the Serbian territory.

A group of young refugee girls joyfully posing for a Polaroid by a small camp by Chios town center.

Chios, Chios Island, Greece, May 2016

Detail of daily life in the barracks behind Belgrade train station.

Belgrade train station, Belgrade, Serbia, 2017

Giovanna Del Sarto: Website | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to use photos by Giovanna Del Sarto.

Related Articles:

Interview: Inspiring Woman Spreads Joy By Giving Soccer Balls to Children in Refugee Camps

Incredible Woman Created a Catering Company to Help Employ Palestinian Refugee Women

Powerful Portraits of the “Invisible Children” Growing Up as Refugees

WWII Refugees Send Heartwarming Letters of Hope to Syrian Children

Eye-Opening Photos Reveal How Refugee Children Today Are Same as Those From World War II