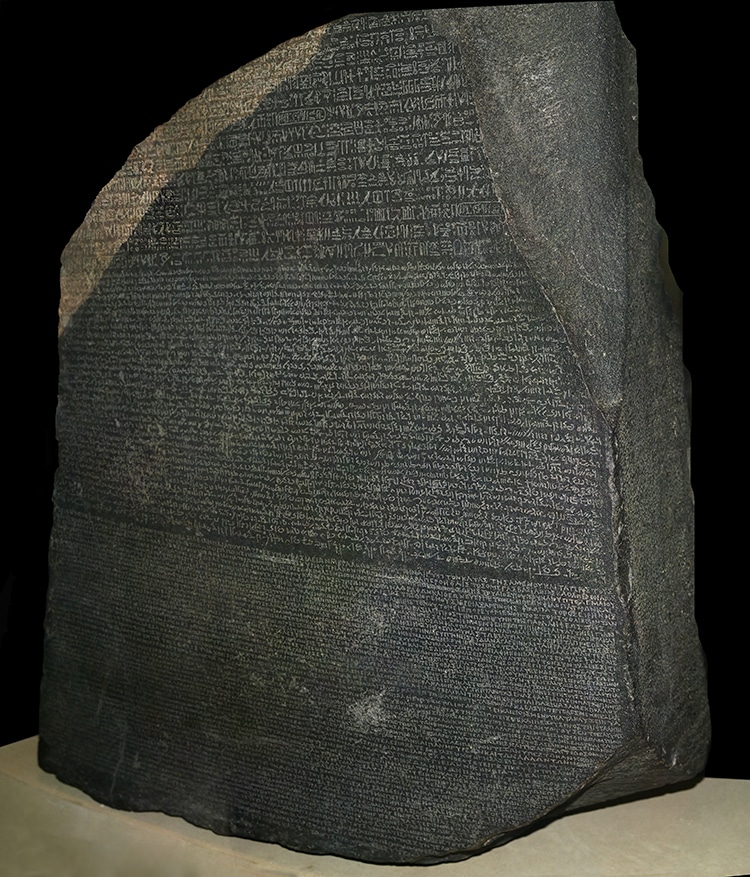

The Rosetta Stone is currently housed in The British Museum. (Photo: © Hans Hillewaert via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Rosetta Stone is one of the most famous ancient Egyptian artifacts. The 1,680-pound granodiorite stone was first discovered in 1799 by a French soldier on Napoleon's Egyptian campaign. The military mission—which also served as a convenient mechanism for colonial pillaging—brought the giant slab to Europe. By 1802, the stone fell into the hands of the victorious British, and it has sat in The British Museum ever since. Inscribed with three scripts in use during the second century BCE Egypt, what does the monumental Rosetta Stone actually say?

The three sections of text are written once in Egyptian hieroglyphs, often used for priestly decrees. Demotic, the script largely used by average Egyptians, is also included. Lastly, Ancient Greek, the language of the Greco-Macedonian rulers of Egypt's complex state, rounds out the trio of texts. While some lines have been lost to breakage, the text is quite legible. However, the ability to read hieroglyphs was lost around the fourth century CE. The discovery of the stone's parallel texts was critical to the decoding of the hieroglyph system by Jean-François Champollion in 1822.

The text of the stone announces the decree of a council of priests regarding the young pharaoh Ptolemy V. The 13-year-old boy king had just been crowned that year, 196 BCE The priests announced that he should be honored—as Egyptian kings typically were—with statues in temples, birthday celebrations, processions, and his accession noted on official records. The decree also mandates many copies of its text be engraved and posted around the country in temples. Archeologists have found other copies of the decree, suggesting it was in fact widely disseminated.

The Rosetta Stone may be the most well-known example, but countless other Egyptian written records exist. Industry and the state were exceptionally well-organized—even attendance was kept on the job. Many of these records are currently held by museums outside of Egypt, including an expansive collection housed at The British Museum. Many activists and archeologists have called for the return of such artifacts, which are national treasures that—like the Rosetta Stone—were often taken during periods of colonial oppression and invasion. The Rosetta Stone, too, has recently been central to calls for repatriation.

The famous Rosetta Stone is actually a priestly decree honoring Ptolemy V Epiphanes, the Egyptian pharaoh.

h/t: [Open Culture]

Related Articles:

Researchers Use DNA to Reconstruct the Faces of Three Ancient Egyptian Mummies

8 Facts About Hatshepsut, One of the Few Female Pharaohs to Rule Ancient Egypt

All Hail Sobekneferu: Learn About the First Known Female Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt

3,000-Year-Old Canoe Found in Wisconsin Is Oldest One Ever Discovered in Great Lakes