Wilkes battled the elements of an inclement Paris in an 18-hour shoot of the Jardins du Trocadéro and Eiffel Tower from a 40-foot lift truck, 2014. (Photo: © 2019 Stephen Wilkes)

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

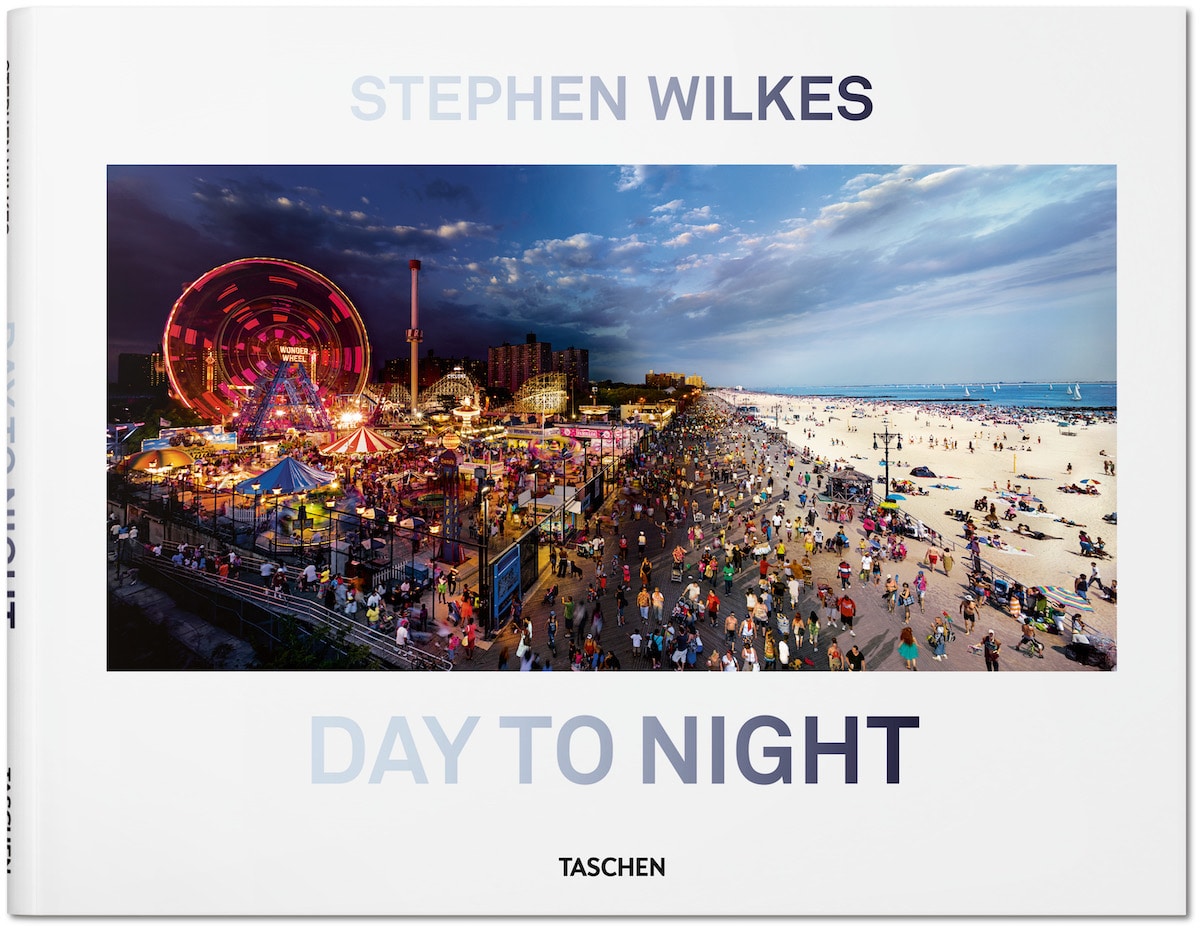

Over the course of ten years, photographer Stephen Wilkes has embarked on an epic project that has led him to photographing locations for hours—and days—on end. The end results are striking photographic compositions that detail the visual changes of a specific place as the day progresses, turning light into darkness. Originating in New York, Wilkes' Day to Night series has spread across the world and out of the urban environment to become incredible photographic time capsules of Earth's great spaces.

Whether battling inclement weather in Paris during an 18-hour shoot or chasing skittish migratory birds, Wilkes' tenacity and passion for his work shine through in the final photographs. Published by Taschen, Day to Night is a new publication that pulls together Wilkes' impressive oeuvre. From the Brooklyn Bridge to the Serengeti, the book is a global tour of the places and events that make our world special.

With this work, Wilkes invites spectators to slow their gaze and drink in the rich detail of each scene. Moments like the Regata Storica in Venice show the pageantry and tradition that helps root this Italian city in its history, while other scenes allow viewers to marvel at the strength of the natural world. Each photograph is rich with detail, and the book lets viewers explore every inch of the composition in order to experience the scene as Wilkes experienced it.

You can now pick up a copy of Day to Night. And in celebration of the publication, Wilkes will show work from the book and new images at Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery in New York. His solo exhibition A Witness to Change will run from September 12, 2019 to October 26, 2019.

My Modern Met had a chance to speak with Wilkes about his work, including how the technology has evolved and how his mission has changed over the course of ten years. Read on for excerpts from our chat.

Brooklyn Bridge Park, 2016. (Photo: © 2019 Stephen Wilkes)

On how Day to Night changed him:

I think I've gone deeper into all the various themes that I love photographically so I think I've grown as an observer. I think it's taught me things. I really feel that it has informed me in a very deep, meaningful way because I think that I have always been curious and I love looking and I love seeing.

The idea of looking and seeing nowadays is becoming an endangered human experience, but I find when I do this work that it is the antithesis. It's constant connectivity that we are all drawn into now, this addiction that we all have to our iPhone and social media. But what I find when I do these pictures is that I get to just look. And in a way, when you have that depth of time to look at something, just study a single place the way I do, it just affects you on a deep level. You begin to see narratives in everything.

Brooklyn Bridge Park, 2016 (detail). (Photo: © 2019 Stephen Wilkes)

On how technology has changed his work:

When I started taking photographs 10 years ago, the largest megapixel large format camera could only shoot, I believe, a one-minute time exposure so you couldn't even do night photography. Shooting an hour exposure of moonlight or anything like that was out of the question. It was a 50 megapixel back. So my first Day to Nights were shot with a 50-megapixel back. My last Day to Night, which I just did, was shot with 150 megapixels. So it's tripled. Image quality has tripled within 10 years. And with that, there's exponential image quality.

My passion in creating imagery has always been about the way I see, and I want to sort of create images that really take you into how I see and what it really looks like—physically the way the human eye sees. Inherently, the way we see an image and the history of photography has always been defined by a format. It could be 35mm, two and a quarter, 4×5, 8×10—that defines where the frame is. You have a lens and then the frame has to fit within whatever that lens projects onto that frame.

What I think is so exciting about the medium right now, and the change I've witnessed over this last 10 years since I started doing this, is that I am no longer defined by a frame. I create the frame based on what I see. I'm exploring the way the human eye works and how we see the world in terms of peripheral vision, in terms of the way we see scale. These are things that this technology has allowed me to dive into.

A couple embraces amid the flux of pedestrians in London’s Trafalgar Square, 2013. (Photo: © 2019 Stephen Wilkes)

On the experience he likes to give the viewer:

I'm trying to create a visceral experience in my photographs. I want you to almost feel like you're looking through a window, and I think that's where the medium is going. I think technology has increased. It's like if, as a writer, you'd never heard of a thesaurus. If somebody gave you one, you'd be like “Wow, this is great. I have all these other words I can now work with to describe things.” That's the way I feel about megapixels. I feel like each time we gain more detail, more information. I feel that becomes more potential for additional stories. Things that were insignificant suddenly become significant in my photographs and those details become powerful new ways to reward a viewer when you stand in front of a very large print.

The Grand Canyon’s popular South Rim as seen from the 70-foot-high Desert View Watchtower. Arizona, 2015. (Photo: © 2019 Stephen Wilkes)

On how Day to Night has evolved from cityscape to landscape:

The work has evolved now into endangered species and endangered habitats, which are big themes in my documentary work, but really only in the last few years has it really come through in Day to Night when I started the bird migration series with National Geographic.

I did the National Park series. That's when I started to sort of see that I could create a narrative photographing landscapes and places that are outside of the cityscape. The work really originated in New York City. It was my sort of love letter to New York. But as I started photographing the city, I started to see things that were connecting me in ways to nature. When you see people in New York City from 40 to 50 feet in the air and study them over an 18-hour period, there's a sense that people in cars and taxis, and the way New York moves, the flow and the energy of New York City becomes very reminiscent of almost when—if you've ever snorkeled—you see school of fish.

They're all individuals, but they all move in this sort of beautiful emergent behavior, harmonic motion. So I started to see things like that. It's been a wonderful, extraordinary gift that I sort of stepped into.

Steeple Jason, Falkland Islands, 2017. (Photo: © 2019 Stephen Wilkes)

On what's been his biggest challenge:

I would say, recently I think the work has gotten more challenging over the years and that's partly because of my nature. I love challenges, and so as the work has grown—it wasn't enough to stand in a crane for 18 hours and shoot people and cityscapes. Now I'm shooting wildlife. So many of my buddies and colleagues at National Geographic—these are guys that spend their lives documenting just one species—they hear what I'm doing and they go, “So how many weeks are they going to give you to do this thing?”

“Actually, it's called Day to Night.” They look at me like, “Oh, yeah, good luck,” at the idea that the birds are just going to show up for me on that day, but I've been very, very lucky and I go in with a certain kind of attitude. I'm hopeful and I do my homework, but what I like to say is that I live in the moment.

I think the most challenging ones I've done would absolutely be the bird series because they're such skittish creatures, especially the Sandhill cranes, where you have to photograph a species that's essentially hunted most places in the world. You're intimately close to them in a blind for 36 hours in which I can't move and can't turn a light on—that kind of thing. I mean, those are really, really challenging situations.

Serengeti National Park, Tanzania, 2015. Steeple Jason, Falkland Islands, 2017. (Photo: © 2019 Stephen Wilkes)

On his interest in conservation:

Conservation and what's happening in our world right now is the single most important issue that I live with—I think we're living with as humanity—and I feel, in a way, that if I only have so many years to continue to do this type of work because it's obviously very physical and enormously labor-intensive, I want to do pictures that depict where we are in this moment in time. Hopefully, that can inspire people who want to recognize why we have to start taking action now.

One of the things that I feel very strongly about is that as I've gone to all these places, as I documented bird migration around the world, and the Serengeti, and all these different places, I feel more strongly than ever that everything is truly connected. So when we tip certain ecosystems, it creates this huge domino effect. I have witnessed animals communicate on a scale that I never thought could exist and I'm really interested in sort of telling that story to reinforce that message.

Gondoliers take to the Grand Canal in 16th-century-style boats and garb for the annual Venice Regata Storica, 2015.

On what he hopes people take away from Day to Night:

When you look at my book, the hope I have is that it really affects the way you see. You look at a Day to Night and you'll see it in the book. Then I take you into the details of that picture, and in many of the photographs, they are like pictures within pictures within pictures and I think that's really the joy that I have in looking and in seeing.

I hope that when people go through the book that they have that experience, that sort of joyous ability to discover, “Oh my God, what was happening here?” or “Wait a second, that's in this picture?,” And they go back and forth. You know, they look at the actual whole Day to Night image and then flip back to the detail and they realize, that's a detail within the picture. It's a sense of discovery that I think, for me, is one of the joys that I have as an artist and as a human being. This idea of looking at something and discovering something and that's what I hope for. It's a celebration of beauty and our world, in a way, and I hope that through that celebration that it becomes an entry point emotionally. I'm hoping for people to look at the world, see all the good beauty that we have, and also recognize at the same time how fragile it is.