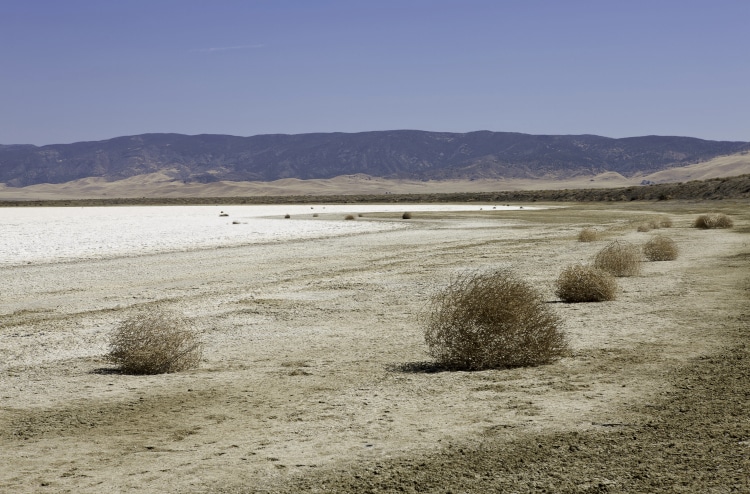

Photo: photosketch/Depositphotos

Few plants are as uniquely symbolic of the American West as the lone tumbleweed. In pop culture, it has come to signify desolation, emptiness, and even boredom—almost growing into its own movie trope. It has also been a staple of Western movies, acting like a desert prop that points to the soon-to-be-tapped potential of a small town. But despite its place in the American imagination, many are unfamiliar with its origins. Not only is the tumbleweed not native to North America but it's also caused trouble since its arrival.

Tumbleweed is one of the many common names of the Russian thistle (Salsola tragus). It is native to dry and semi-dry regions of Europe and central Asia. It is believed the first Russian thistle seeds accidentally arrived in a containment of flaxseed imported from the Russian Empire in the 1870s. The first tumbleweeds on record popped up in the plains of Bonhomme County, South Dakota, where they took over plowed land meant for growing crops.

Soon, the humble tumbleweed traveled for miles on end, becoming one of the fastest plant invasions in the history of the United States. By the turn of the twentieth century, the species had made its way to California. Today, the plant can be found in all states except Alaska and Florida. In addition to spreading across North America, Russian thistle has also been introduced to other parts of the world, such as Europe and South America.

Thanks to its nature, tumbleweed spreads quickly. First, it produces up to 250,000 seeds, depending on the size of the plant. Once the plant dies, it is easily detached from the ground by gusts of wind, which push it around thanks to its round shape, spreading seeds as it bounces along. While it is a soft sapling during its early stage, it then becomes a thorny plant, keeping any herbivores at bay and protecting the seeds prior to release.

Once the seeds have been deposited, they don't need much to grow either. They only need a day temperature of about 68°F and 41°F at night to sprout. On top of that, they've adapted to alkaline and saline soils. This means they can grow in places with naturally reduced vegetation, whether it is land that has been cleared for agriculture or areas where they can easily compete with and take over space from native vegetation.

While at first it caused many issues for American farmers, such as crop losses and injuries to the livestock that tried to eat it, it's less of an agricultural problem today and more of a threat due to human actions and climate change. For example, its flammable branches can help spread wildfires, be a host for insects that transmit diseases, cause traffic accidents, and clog roads.

But despite all the bad things, some are thankful for their ubiquitous presence. In the 1930s, a severe period of drought in the South known as the Dust Bowl saw families turning to young tumbleweeds—the only plant that continued to grow—to feed their livestock and even themselves. Should you ever encounter one on a road trip or in your backyard, you'll know there's much more to this humble plant than the tumbles it took to reach where you are.

Not only is tumbleweed, or Russian thistle, not native to North America, it's an invasive species.

Photo: jeremyn/Depositphotos

It is believed the first Russian thistle seeds accidentally arrived in a containment of flaxseed imported from the Russian Empire in the 1870s.

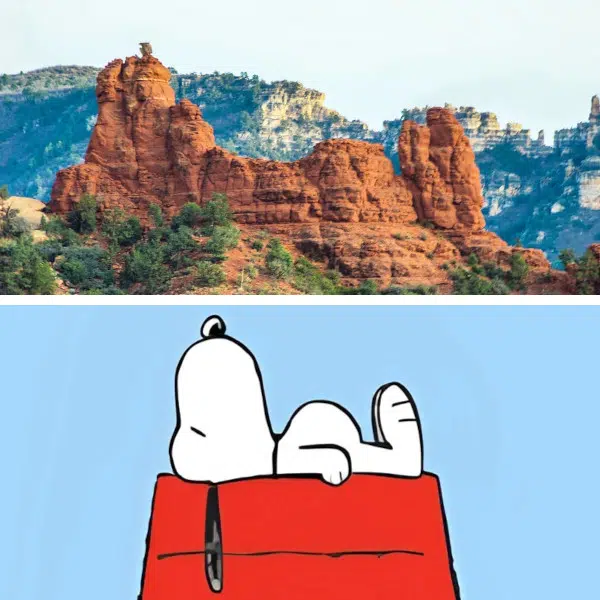

Photo: SharpShooter/Depositphotos

Soon, the humble tumbleweed traveled for miles on end, becoming one of the fastest plant invasions in the history of the United States.

Photo: MaciejBledowski/Depositphotos

h/t: [National History Museum]

Related Articles:

Intelligent Orangutan Treats His Own Facial Injury with Medicinal Plant

Emily Dickinson’s Collection of Plants and Flowers Now Viewable Online for Free

Colorful “Map of Plants” Visualizes the Complex Diversity and Evolution of Our Planet’s Flora

This Plant-Powered Trap Will Help You Get Rid of Mosquitos To Make the Most Out of Your Summer