Photo: Amador Loureiro

These days, thanks to smartphones, almost everyone has a camera with them at any given moment. With the resurgence of digital cameras, photography’s impact on the world is more evident than ever. Rewinding time, before selfies were a cultural norm, before geniuses like Cindy Sherman and Andrea Gursky elevated photography to an art form, someone had to invent this piece of technology. So, who invented the camera? And how has it evolved over time into the piece of equipment we now know? Let's take a look at how this revolutionary invention changed how we document life.

The Pinhole Camera and Camera Obscura

Ancestors of the photographic camera, both camera obscura and the pinhole camera, date back to the ancient Greeks and Chinese. In fact, Chinese philosopher Mozi, who lived during the Han dynasty (circa 468 – circa 391 BC), was the first person to write down the principles of camera obscura. Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle also wrote his musings about the phenomenon in his book Problems, wondering why the sun appears circular even when projected through a rectangular hole.

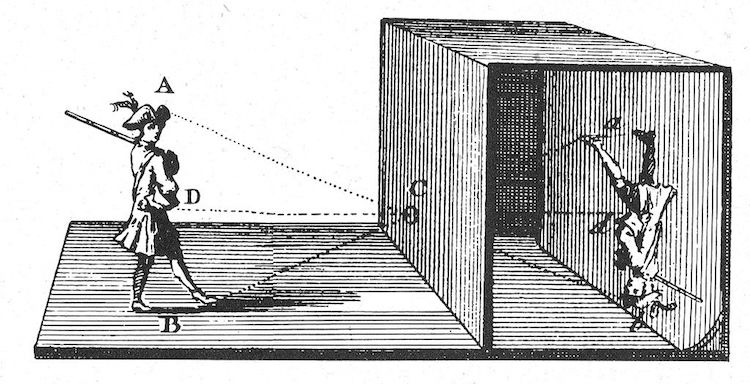

So, what is camera obscura? This basic principle is a natural optical phenomenon where an image on one side of a wall—or screen—is projected through a small hole onto a surface opposite the opening. The resulting projection is upside down. Camera obscura, a term coined in the 16th century, also refers to a box, tent, or room set up for such projections.

An illustration of the principles of camera obscura. (Photo: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

The only difference between a camera obscura and a pinhole camera is that a camera obscura uses a lens, while a pinhole camera is a similar device, but with an open hole. This technology picked up steam through the 17th and 18th centuries when artists used these devices to help project drawings they could then trace. The only issue with this system is that, clearly, aside from tracing, there was no way to preserve the images.

That's where the next step on the road to the first photographic camera comes into play.

Johann Zahn, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, and the Invention of the Camera

While early camera obscura devices took up entire rooms, by the 17th century, developments led to portable devices. Further advancements, like the invention of the magic lantern, further pushed what was possible with projection but didn't solve the issue of capturing still images.

German author Johann Zahn, an expert on light, wrote extensively about the camera obscura, magic lantern, telescopes, and lenses. In 1685, he proposed a design for the first handheld reflex camera. Ahead of his time, it would take another 150 years before his invention became a reality.

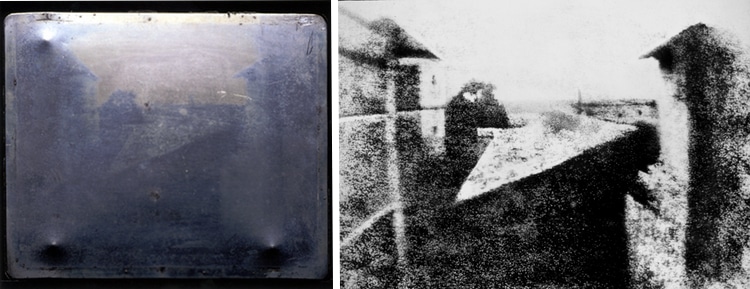

Left: Niépce's original photo plate c. 1826 (Photo: via Wikimedia Commons) | Right: Enhanced version by Helmut Gersheim (1913–1995), performed ca. 1952, of Niépce's View from the Window at Le Gras. (Photo: Joseph Nicéphore Niépce [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

Using a technique he called heliography, the French inventor was able to produce one-of-a-kind images that could not be replicated. Heliography calls for a glass or metal surface to be coated in Bitumen of Judea. This naturally occurring asphalt would harden in the brightest areas, while the unhardened bitumen would be washed away, leaving behind the photographic imprint. This is still a long way off from photography as we now think of it, but it was a revolutionary step towards permanent replicable photographs.

Daguerreotype camera from 1839. (Photo: Liudmila & Nelson [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

Louis Daguerre and Daguerreotype

In 1829, Niépce joined forces with Louis Daguerre, a French artist and photographer. Together, they continued to experiment and refine the process for taking photographs. Several days of exposure time were needed to develop Niépce's bitumen-soaked plates. Surely, there had to be a better way. After Niécpe's death in 1833, Daguerre continued to hone his process and eventually developed the daguerreotype.

Carrying his name, it would be the most commonly used photographic method for the next twenty years. The process was introduced publicly in 1839 and called for a sheet of silver-plated copper to be polished to a mirror surface. The plate would be treated with iodine vapor to make it light sensitive and after exposure in the camera, would be exposed to mercury vapor and fixed with sodium chloride. Using this method, Daguerre was responsible for taking the first photograph to include human beings.

Daguerre's methodology spread rapidly, and by 1840, Alexander Wolcott was issued the first American patent in photography for his daguerreotype camera. Still, the process was expensive, limiting photography to professionals and making a photograph a precious one-of-a-kind keepsake for an elite few.

Left: Latticed window at Lacock Abbey, August 1835. A positive from what may be the oldest existing camera negative. (Photo: William Fox Talbot (1800-1877) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons) | Left: A salted paper calotype photograph of Scottish amateur golfer, golf administrator, and aristocrat James Ogilvie Fairlie, c. 1846-49 (Photo: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Invention of the Photo Negative

To this point, photographs were still one-off items, printed originals that could not be reproduced. This all changed thanks to William Henry Fox Talbot. Scientist and inventor, the Brit developed light-sensitive paper and a process known as calotype, which would lay the foundation of photography up to the digital photography age.

Around the same time that Daguerre was perfecting his process, Fox Talbot had a different method for quick and accessible photographs. It started with his “salted paper,” where he soaked ordinary writing paper in a weak solution of ordinary table salt. Then, by brushing one side with a silver nitrate solution, he effectively produced a light-sensitive paper that could be used for photograms or capturing images from the lens of a camera. Though it still took a few hours of exposure to produce a legible image, the inventor was able to come up with a method to fix the photo print. This was a huge step that hadn't previously been accomplished and allowed copies of the photo to be printed simply by placing new light-sensitive paper against the fixed photograph—or negative.

By late 1840, Fox Talbot revealed his calotype process for developing photographs. With calotype, a latent image could be produced with just a few minutes of exposure if done in bright sunlight. This was a giant leap forward, as calotype also produced a negative that allowed for multiple replicas through contact printing—a true revolution in photography.

Frances Benjamin Johnston with a group of children looking at her Kodak camera, 1890. (Photo: Library of Congress)

George Eastman, Kodak, and Cameras for Consumers

If we want to look at how photographic cameras came into the hands of the public at large, it's impossible not to speak about George Eastman. In 1884, Eastman patented the very first practical roll film. In 1888, the photographer introduced the first box camera widely used by consumers, the Kodak Black camera, which benefited from advances in technology. By this time, gelatin dry plates, which developed quickly, meant that people did not need a tripod for their cameras, and thus the first handheld cameras started being sold.

As opposed to other cameras, Eastman's Kodak was genius in its use of flexible film. He originally used a roll of paper before switching to roll film made from celluloid instead of the glass plates that were the norm. Rid of bulky plates, the Kodak was truly portable. Easy to use, it helped move photography from a strictly a profession to a hobby that amateurs could also enjoy. Kodak Black cameras were sold with the film already inside, and photographers simply mailed the entire camera to the Kodak headquarters in Rochester, New York, to have their pictures developed and mailed back.

Kodak Brownie 2 camera. (Photo: Håkan Svensson via Wikimedia Commons)

Kodak's beloved Brownie was introduced just two years after the original camera Eastman produced. Now, instead of coming preloaded, the Brownie came with a removable film container. Less expensive than the Kodak Black, coupled with the plus of not having to ship the entire camera to get your photos back, the Brownie caused a sensation and helped popularize amateur photography.

From the mid-19th century onwards, photo technology rapidly developed as inventors pushed the envelope for how to take still images. In the early 20th century, things reached a peak with the development of the compact camera, the viewfinder, the Polaroid camera, and eventually, the digital SLR camera (DSLR).

Today, these significant developments have paved the way for a wide range of digital cameras, making brands like Sony, Nikon, and Canon synonymous with cutting-edge imaging technology and their names integral to the photography world.

From glass plates to paper prints to digital photograph imaging, the photo revolution's intention remains the same—to immortalize our world.

Related Articles:

Mathew Brady, the Story of the Man Who Photographed the Civil War

A Brief History Lesson in Tintype Photography

The History of Photojournalism. How Photography Changed the Way We Receive News.

Take a Wide-Ranging Look At the History of Panoramic Photos, From the Civil War to the iPhone